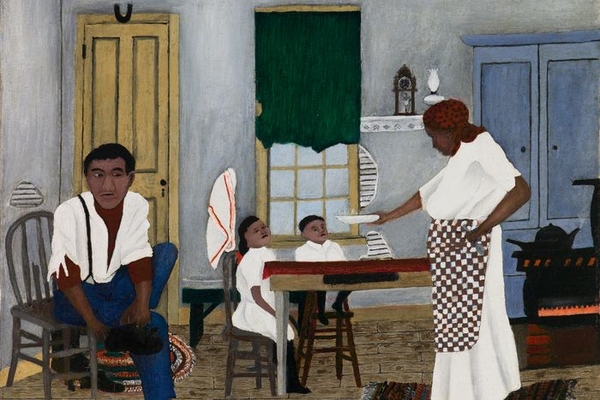

Horace Pippin's "Sunday Morning Breakfast" (1943) exudes charm. In a seemingly plain, straightforward way, it captures a black family sharing a meal on the Sabbath, a treasured moment in simpler times, before television, Sunday business hours and other modern distractions were widely adopted. Look a little closer, however, and the painting, owned by the Saint Louis Art Museum, becomes much more. Quietly, and with great acuity, Pippin telegraphs the family's impoverished state and, perhaps because of that, suggests tension in the domestic dynamic just beneath the surface.

Within a year, the Museum of Modern Art displayed four Pippin canvases in a 1938 exhibition titled "Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America," which also traveled to other venues. Several museums soon bought his works and, along with galleries, gave him solo shows. Competitions awarded him prestigious prizes. And collectors including Albert C. Barnes, founder of the spectacular Barnes Foundation now in Philadelphia, purchased his paintings, which they praised for their simplicity and naïve character. (Pippin enrolled in art classes at the Barnes around 1940, but he soon left, preferring to learn on his own.)

Within a year, the Museum of Modern Art displayed four Pippin canvases in a 1938 exhibition titled "Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America," which also traveled to other venues. Several museums soon bought his works and, along with galleries, gave him solo shows. Competitions awarded him prestigious prizes. And collectors including Albert C. Barnes, founder of the spectacular Barnes Foundation now in Philadelphia, purchased his paintings, which they praised for their simplicity and naïve character. (Pippin enrolled in art classes at the Barnes around 1940, but he soon left, preferring to learn on his own.)

During his career, Pippin took up several themes: war, racism, biblical stories, portraits, still lifes and genre paintings depicting life among African-Americans. When, in the mid-1990s, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts organized a traveling show of his works, it was aptly titled with his own words: "I tell my heart." Another exhibition, at the Brandywine Museum of Art in 2015, used as its title the last part of a quote from Pippin explaining his art: "I paint it exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it."

"Sunday Morning Breakfast" lives up to both characterizations. In it, Pippin recalls a kitchen scene from memory. His simple setting seems to be a sea of tranquility, created partly by its mostly soft palette and partly by its eye-pleasing symmetry. The double-paneled beige door on the left is balanced by the double-door blue cabinet on the right. The father's white shirt corresponds with the mother's flowing white dress, and the two children also wear white. The green curtain cuts a vertical down the center of the painting, offset by a thinner horizontal line suggested by the black bench, maroon tablecloth and black stove.

This moment in time isn't static, though. Pippin adds life by painting steam emanating from the kettle on the stove, the mother walking toward children waiting patiently for their food, the father putting on a shoe. Viewers can easily imagine that Pippin did witness such a tableau and is showing exactly what he saw.

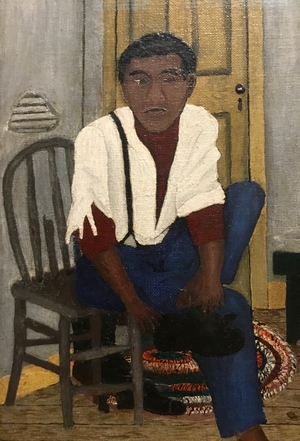

To put his heart into the scene, Pippin uses details, like the patterned bandanna and apron worn by the mother, the humble hooked rugs, the glowing stove and the awkward little shelf, with its clock and lamp, near the cupboard. He suggests the family's poverty with the broken chair back, exposed wallboards and ragged curtain. Above the door, he painted an inverted horseshoe, a hopeful symbol meant to bring needed luck to the household. He places the father on the edge of his chair, apart from the rest, and portrays his eyes looking not at his family, but warily to his left. Worried, perhaps? The mother, who is barefoot, doesn't look up from her children, who seem to be sharing one plate of food—and eagerly awaiting it.

To put his heart into the scene, Pippin uses details, like the patterned bandanna and apron worn by the mother, the humble hooked rugs, the glowing stove and the awkward little shelf, with its clock and lamp, near the cupboard. He suggests the family's poverty with the broken chair back, exposed wallboards and ragged curtain. Above the door, he painted an inverted horseshoe, a hopeful symbol meant to bring needed luck to the household. He places the father on the edge of his chair, apart from the rest, and portrays his eyes looking not at his family, but warily to his left. Worried, perhaps? The mother, who is barefoot, doesn't look up from her children, who seem to be sharing one plate of food—and eagerly awaiting it.

The family mood Pippin creates here is, in an understated way, as skillful as (and reminds one of) the tense family dynamic masterfully portrayed in "The Bellelli Family" (1858-59, revised c. 1867) by Edgar Degas.

"Sunday Morning Breakfast," like the other domestic scenes for which Pippin is renowned, never veers into the maudlin. Nor is it didactic. In his own balanced way, Pippin has focused attention on a portion of American society that was largely ignored by other accomplished artists of his times. It is social commentary at its subtlest.