Los Angeles

A portrait, by definition, is personal, and Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98-1543) is celebrated as a master of them. So a wander through "Holbein: Capturing Character in the Renaissance," at the J. Paul Getty Museum through Jan. 9, 2022, might seem confounding. His pictures seem similar. Most are small, with some measuring just a few inches across. All are half- or three-quarter length images, and most are set against a marine blue background. The sitters often look away, avoiding the viewer's gaze. They clasp their hands together or clutch an object. Many seem grim.

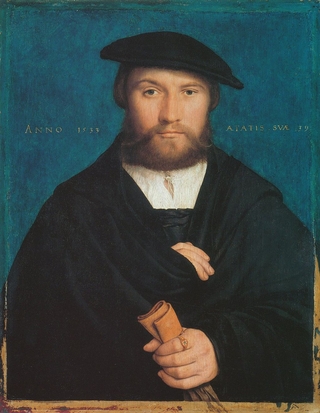

"A Member of the Wedigh Family" |

Why, then, are they so compelling? Clearly, they are all well-modeled and finely painted with precise brushwork, yet there's more to it. In "A Member of the Wedigh Family," Holbein reveals—in a Latin inscription written in gold—only that he painted this handsome man in "The year 1533" and "At the age of 39." But he gives other hints. The man's gold ring, prominently displayed on a hand holding a neatly folded pair of gloves, carries the coat of arms of the Wedighs, merchants from Cologne who were members of the Hanseatic League. Various shades of black illuminate the folds of his substantial garments, which open to show a white shirt, delicately tied at the neck, suggesting his valued position in life. Then, slyly, Holbein brings him alive, even a little flirtatious, by painting a raised eyebrow over his enlarged right eye.

"A Lady With A Squirrel..." |

Holbein's portraits require close looking, and this show presents a rare opportunity to do that. It is the first major museum exhibition of Holbein's paintings in the U.S., according to the Getty and its co-organizer, the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, where the exhibition will move in February. Such is the occasion that the Frick Collection, for the first time ever, lent two of Holbein's most famous works: " Thomas Cromwell " (1532–33), the shifty-eyed chief minister to Henry VIII, is on view at the Getty, and "Sir Thomas More" (1527), Henry's onetime Lord High Chancellor turned religious opponent, will travel down New York's Madison Avenue to the Morgan.

Born and raised in Augsburg, Germany, Holbein came from a family of artists and was trained by his father, also named Hans Holbein. He made his first mark in Basel, Switzerland, where he had moved with his family in 1515, and hit his high point in England, where he twice lived, 1526-28 and 1532-43, when he died, likely of the plague. Henry VIII appointed him court painter by 1536.

"Bonifacius Amerbach" |

He was, according to Anne T. Woollett, the Getty curator who organized the exhibition, a genial creator who collaborated with his clients, choosing props, inscriptions and formats in tune with the "Renaissance culture of self-definition, luxury, knowledge, and wit" to indicate "their interests as well as their rank and status."

All of that is evident in the first picture visitors see. "A Lady With a Squirrel and a Starling ( Anne Lovell ?)" (c. 1526-28) portrays a serious, fine-featured woman in a white ermine pointed cap, a shawl covering her diaphanous white chemise and a black dress, against that Holbein blue. She is holding a red squirrel that munches on a hazelnut; his tail covers her decolletage. A gleaming bird sits on a branch close to her ear.

"Simon George" |

The sitter belongs to the upper class, but what of the animals? Art historians decoded their meaning in 2004 when, noting that the Lovell family crest contained six red squirrels, they tentatively identified the sitter. The date—Holbein painted the portrait not long after Anne's husband, Francis Lovell, inherited an estate in East Harling—gave another clue. Technical analysis shows that he added the squirrel and the starling, a pun on the estate's location, late in his process, likely at the couple's request, probably to signal their newfound position as landed gentry.

Holbein began developing his portrait philosophy as the "celebrity scholar" Desiderius Erasmus was arguing that the written word outranked the visual image in portraying character. He nonetheless used Holbein's portraits to attract more followers. One of them (c. 1532), showing a serious, graying Erasmus, is on view.

But an earlier, more striking portrait, " Bonifacius Amerbach " (1519), far better captures Holbein's aim to create what the catalog calls "the speaking image." Amerbach, a young friend to Erasmus, appears in profile, dressed in a dark, fur-trimmed coat over a patterned blue shirt and floppy hat. On a tree at his side hangs a white tablet that in Latin reads in part, "Although only a painted likeness, I am not inferior to the living face."

"Mary, Lady Guildford" |

Again and again, the exhibition amply demonstrates that—and captures character. For the projection of power, there's Cromwell. For attitude and arrogance, there's " Richard Southwell " (1536), a onetime sheriff, Cromwell associate, possible murderer and privy counselor. For prosperity and stern piety, there's "Mary, Lady Guildford" (1527). There is also beauty, shown well in " Simon George of Cornwall" (c. 1535-40), a roundel profile of a handsome, well-dressed man who—signaled by the red flower he holds and the Leda and the Swan image on his hat badge—might be in love.

Holbein was far from the only artist doling out symbols in his portraits in this era. But in his very distinctive way, Holbein did it exquisitely.