New York

To celebrate its 60th anniversary, the American Folk Art Museum is presenting an exuberant display of some 400 objects that convey the breadth and depth of the 8,000 pieces in its collection. "Multitudes," fortuitously, also marks something even more important than a diamond jubilee: 10 years of stability after years of a nomadic existence and a near-death experience in 2011, when over-ambitious expansion plans forced the museum to sell its flashy, 10-year-old building to pay off debt and to explore a sale of the collection.

"Girl in A Red Dress..." |

Along with the expected quilts, duck decoys (a wall of them!) and needlework samplers, visitors to "Multitudes" will see a case of hand-tinted vernacular photographs (taken as early as 1915); mid-20th-century "thread paintings"; 21st-century sculptures made from leaves, wood and clementine peels; and a range of drawings, paintings, collages and photographs by self-taught "outsider" artists like Henry Darger (1892-1973), the janitor whose works can be found at the Museum of Modern Art, among others. Most embody the traditional definition of folk art—everyday objects, frequently functional, crafted by people lacking in a formal art education. Others stretch it, often into darker corners.

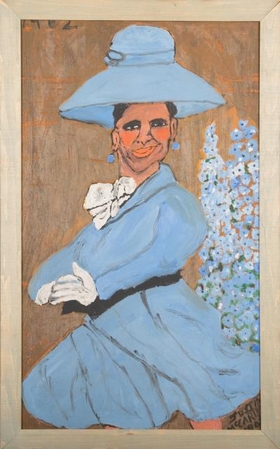

"Blue Woman..." |

Consider the sculptures of Annie Hooper (1897-1986). Around 1947, after completing treatment for mental illness (related to her husband's and son's service in World War II), she began to fashion figures that illustrate biblical scenes from driftwood, cement, paint and shells. Eventually, these pale, lumpy, slouchy forms filled her home. Here, dozens of them—angels, disciples of Christ, witnesses to the crucifixion (1950s-1986)—convey the unbroken faith that anchored Hooper's life but also transmit an incongruous mix of hope and sadness.

William Edmondson (1874-1951), too, felt called to make religious sculptures, which he carved from limestone. Here, his "Martha and Mary" (between 1931 and 1937) depicts the New Testament sisters sitting side by side, hands folded at their waist, as Martha uncharacteristically has abandoned her food preparation to listen to Jesus. Spare in detail, and just 15 inches tall, Edmondson's sculpture nonetheless seems monumental.

Philip Pellegrino (1919-1997) put his busy hands to work in an entirely different enterprise. A shoemaker by trade, Pellegrino repurposed his leather scraps into ingenious miniature sculptures (1950s-60s): tiny bowler hats, fantastical pipes, revolvers, animals, naked figures and a larger bust resembling Lurch of the Addams Family, carved from piled-up layers of leather. Pellegrino tried to sell them, but admirers balked at paying for them; only upon his retirement was he finally able to find folk-art galleries willing to handle his works.

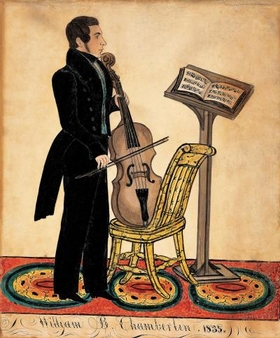

An 1835 watercolor by Joseph H. Davis |

Mary K. Borkowski (1916-2008), abused by a violent husband, created what she termed thread paintings—colorful layered fabrics with generally spare images—not only to record her suffering but also, she said, to keep her "from going crazy." Her "Indifference" (1967) poignantly shows two hands grasping for an escape, watched by witnesses above.

Trade Sign for a Livery Business, 1895-1905 |

The curators, Emelie Gevalt and Valérie Rousseau, also give visitors a healthy sampling of miniature portraits; frilly, calligraphic fraktur documents; trade signs; whimsy bottles; and a mechanical Noah's Ark (1790-1814), made of bone and wood, that sits below a marvelous "Map of the Animal Kingdom" (1835), likely made by an accomplished New England student.

"Multitudes," to use a folksy word, is a crowded cornucopia, and a good reason to raise a glass to the future of the American Folk Art Museum.