When Terry J. Lundgren, the chief executive of Macy's, received Carnegie Hall's Medal of Excellence in April 2008, he beamed with pride. Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg presented the award, which goes to a business leader who supports the arts. More than 1,000 guests, including Martha Stewart, Leonard Lauder and Tommy Hilfiger, cheered from their tables in the Waldorf-Astoria's Grand Ballroom. Tony Bennett sang his heart out. And Carnegie Hall raised $4.2 million.

But when it came time to select an honoree for this year's medal, Carnegie Hall's board and management were stumped. They canceled the benefit.

But when it came time to select an honoree for this year's medal, Carnegie Hall's board and management were stumped. They canceled the benefit.

Why? Because an honoree is not chosen just to give a speech and be feted. He or she must be willing to make a big donation, usually from the company's coffers, and — more important — to invite friends and contacts to the gala who will buy $20,000 tables or single tickets for $2,000 to $3,000, bringing new support to the organization.

With banks, brokerage houses, real estate firms, hedge funds and even law firms struggling for survival, Carnegie Hall realized it had nowhere to turn as it contemplated a gala for this year.

"We simply didn't feel that last fall was the right time to be asking companies and business leaders to make large event commitments," said Susan J. Brady, director of development.

The time-honored system of black-tie charity tributes is breaking down, another casualty of the worst economic climate in decades. "This idea of getting on the phone and saying, 'Wouldn't you like to be honored at our gala?' — that's more difficult, more challenging now than in my 30 years of experience at this," said Will Maitland Weiss, executive director of the Arts and Business Council of New York, which encourages companies to support the arts.

With honorees in short supply, the entire fund-raising ecosystem on which many nonprofit institutions depend — especially those reliant on the financial sector — is endangered. Despite the high costs of mounting a benefit, most nonprofit groups — environmental, health, social service, cultural and educational — try them at one time or another. How much a group gleans from a gala varies dramatically: for some, it's a few percentage points of the annual budget; for others, one big party in a hotel ballroom pulls in the bulk of a year's expenses.

The most coveted honorees are men and women who can lean on the people they do business with. "The issue," says Jason H. Wright, a former senior vice president for public affairs at Merrill Lynch who sits on three nonprofit boards, "is 'Do you have a list?' When you're a corporate executive, you've got suppliers from accountants to printers to whatever to ask." When you're a chief executive, other chief executives reciprocate. And when you're an executive from a glamour business — Wall Street once qualified — your appeal goes further, to people who will pay for a chance to meet you.

(On April 27, the Film Society of Lincoln Center honored Tom Hanks; it was no coincidence that tables at up to $50,000 for 10 guests were bought by Sony, Imagine Entertainment and Creative Artists Agency, companies that depend in part on the star.)

IN the past, the call to be a gala honoree was coveted in the business world. It signified arrival, achievement, statesmanship. Some on-the-rise executives even hired public relations experts to find them honors.

But not this annus horribilis. Nonprofit endowments — like everyone's 401(k) — are down 25 to 30 percent, and fund-raisers are scrambling to fill budget gaps. Although it's too early to measure the decline in giving statistically (reports won't be out for a year or two), over all, Mr. Weiss said, "There's no question that this is the worst — worse than 1987, worse than 9/11."

"If you pick up the phone now and call somebody and say, 'We want to honor you this year,' the answer is 'Not now, not this year,' " he added. "They are saying, 'I am not going to give you a list of vendors and telling them I expect them to buy a $25,000 table.' "

Deborah Hays, deputy director for development at ArtsConnection, which provides arts education programs for schools, is one of those who decided not to make a call. ArtsConnection — which had recently honored Kerry K. Killinger, the onetime chief executive of the defunct Washington Mutual bank — dispensed with its traditional spring benefit in favor of small dinner parties.

"People don't seem to want to be high profile and corporations don't want to be high profile," Ms. Hays said.

Just as potential honorees don't want to pressure contacts to buy tables, neither do they want to be embarrassed if their "list" doesn't buy enough tickets.

Across New York — where the spring benefit season is in high gear — development officers, benefit organizers and nonprofit board members told similar stories; some said they had heard that many executives had declined the honors. But most refused to go on the record. "We don't want our honoree to know he was the third or fourth choice," one explained.

Some groups solved the problem by choosing someone from deep in their midst, already committed to the cause. Trouble is, they don't add a new constituency of supporters, and they often lack the requisite cachet.

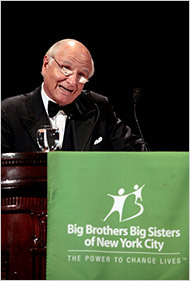

Whereas, for example, Big Brothers Big Sisters of New York City paid tribute to Leslie Moonves, the chief executive of CBS, in 2007, and Brian L. Roberts, the chief of Comcast, the cable TV company, in 2008, this year it honored Edward L. Gardner (pictured, below) on April 28. Mr. Gardner, a trustee for more than 44 years who has raised more than $20 million for the group, heads the Industrial Solvents Corporation.

The "Bigs NYC," as the groups term themselves, declined to comment on Mr. Gardner's glamour quotient. Instead, Michael A. Corriero, the executive director, sent a statement, reading in part: "Without Ed, Big Brothers Big Sisters would be nowhere near the organization it is today."

The "Bigs NYC," as the groups term themselves, declined to comment on Mr. Gardner's glamour quotient. Instead, Michael A. Corriero, the executive director, sent a statement, reading in part: "Without Ed, Big Brothers Big Sisters would be nowhere near the organization it is today."

Instead of canceling a gala, some groups have gone ahead without an honoree. Others, particularly those in culture, can draw from the artistic, rather than the business, community, capitalizing on their glamour. The Martha Graham Dance Company, for example, will honor the musician Phoebe Snow, whose mother danced for the company, and Paul Szilard, the dance impresario, on May 14.

A few groups did manage to recruit honorees from Wall Street. Boys & Girls Clubs nabbed Kenneth Chenault, the chief executive of American Express, for its June 3 gala at the Waldorf, even though the company has scaled back its philanthropy budget for 2009. "This is a cause that resonates with many of our local merchant partners," said Joanna G. Lambert, an American Express spokeswoman. Equally important, Boys & Girls Clubs asked Mr. Chenault last year, before the worst occurred and before everyone adopted a bunker mentality.

Other groups smartly avoided the financial world. Last year, for example, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation was delighted when John M. Angelo, a hedge fund manager, volunteered to be the honoree at its benefit, which raised a $2 million.

This year, the Runyon foundation is honoring Richard T. Clark, the chief executive of the drug maker Merck, at the Rainbow Room on May 27. "When you do an event in New York City, the financial sector is key to success," said Lorraine W. Egan, the group's executive director. "But we were aware that getting someone from the financial sector would be difficult this year, so it was a natural thing for us to look to our other constituency."

Even when an honoree is listed on a gala invitation this year, it may not mean what it once meant. Some executives agreed to be honored but declined to provide a list of contacts, benefit organizers said. Some committed to buying one table, and that's it. At the Runyon foundation, "Merck made a three-year commitment to us to fund a program at a significant level, in lieu of reaching out to its vendors," Ms. Egan said. "We are completely comfortable with that."

THE honoree problem portends less money from benefits, which have already been retooled for the new era. Cost-cutting has forced switches from dinner events to cocktail receptions, from live music to D.J.s, from filet mignon to chicken. "We lowered our entry-level ticket price, from $750 last year to $500 this year," said LaRue Allen, executive director at Martha Graham. "Many of our supporters are like family, and we wanted to make it possible for our supporters to come."

If anything, nonprofit officials expect the honoree problem to worsen. "We're always thinking about next year, and next year will be as hard, if not harder, than this year," Ms. Egan said.

Even forward-planning carries risks, though. Just ask the New York Botanical Garden. Last summer, it chose John A. Thain, then head of Merrill Lynch, to receive its Founders Award at its annual May benefit dinner. Then came Mr. Thain's downfall: he sold Merrill, whose billions of dollars in losses kept worsening, to Bank of America; pressed for a masters-of-the-universe-size bonus even after the injection of taxpayer money; was forced out of his job; and has been subpoenaed to testify about Merrill's bonuses by New York's attorney general. He's become a symbol of Wall Street hubris, with no vendor list, and hardly a draw.

So, along with Mr. Thain and his wife, says a botanical garden spokesman, the benefit this month will also honor Gregory Long, the institution's president.