For Nasser D. Khalili, an Iranian-born businessman and philanthropist, the Islamic art market is suddenly feeling crowded.

World-Record-Setting Folio from Persian Book of Kings sold at Sotheby's |

But it's not so easy any more. "Twenty years ago, there would be 20 magnificent pieces and four people buying," he says. "Now there will be four major, important pieces if you're lucky and 50 people buying."

The market for Islamic art has been boiling. Even in the United States, where the field has been neglected since the 1979 Iranian revolution, it's gaining buyers. Last November, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened new galleries for Islamic art that in less than eight months attracted 593,000 visitors and helped boost annual attendance to a record-setting 6.3 million. "The Met created huge interest," says Simon Ray, a London dealer.

Around the globe, other museums are also spotlighting Islamic art and augmenting their collections. On Sept. 22, the Louvre will inaugurate a grand pavilion for Islamic art, and next year the Aga Khan Museum will debut in Toronto.

The Gulf States have started or are planning museums, public and private—most notably the five-year-old Museum of Islamic Art in Doha. "They drove the market in the last 10 years," says Brendan Lynch, of London dealers Oliver Forge and Brendan Lynch Ltd.

But he and others believe there is much more buying ahead. "I feel strongly that Islamic art is undervalued in almost every area," says Edward Gibbs, head of the Middle East Department at Sotheby's. For example, "you could build a sensational collection of medieval Islamic ceramics—a world-class, museum-quality collection—for below their long-term value," he says. That's not true of many other sectors of the art market, where great works are scarce or the prices are enormous.

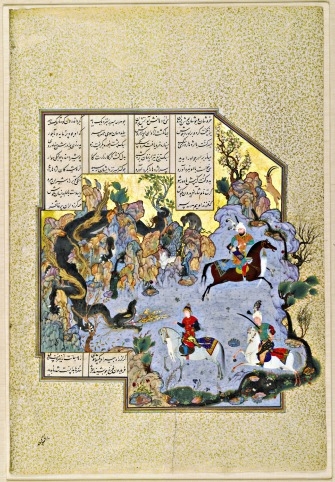

The record price at auction for an Islamic work of art is just under £7.4 million for an illustrated folio from the famed Shahnameh, a 16th-century manuscript chronicling Persian history (also known as the Book of Kings), which sold at Sotheby's in London in April 2011. That's a small fraction of the prices that many contemporary and modern works of art have been fetching. (All auction prices include the commission that buyers must pay; estimates do not.)

Ottoman child's sword at Christie's |

Though sales are growing, totals have varied considerably from year to year. Spring 2011 marked a peak in volume: Combined sales at Sotheby's and Christie's jumped to $78.9 million, plumped by interest in the collection of Stuart Cary Welch, a renowned American scholar of Islamic art, and in pieces from the collection of Simon Digby, an English orientalist.

Last spring, the combined total fell to $23.3 million, partly because there were fewer objects and no star lots. Some buyers felt that some estimates were too high and that some items had been on the market too recently. At Sotheby's, just over half the lots sold. But Mr. Gibbs said that "after the sale, we sold more than 90% of the unsold lots, most at or above" the floor price. At Christie's much smaller sale, about 70% of the lots sold.

Some critics blame the auction houses for pushing the market too aggressively. But William Robinson, Christie's international head of Islamic Art, cites another factor: "It's quite an emotional market. When things are going well, prices go way over the top estimate. Six months later, an identical object gets no response. Or vice versa."

As an example, he cites a 13th-century Seljuk ewer he offered in October 2010, with an estimate of £50,000 to £80,000. It didn't sell. Recycled into the April 2011 sale, with an estimate of £30,000 to £50,000, it soared to £361,250. "It shows how difficult pricing is in this market," he says.

That may be changing now, as the market broadens and loses its reputation as the province of secretive Gulf sheiks and European aesthetes.

SIDEBAR: Iznik Pottery Breaks Out

With origins in more than 50 countries, Islamic art is incredibly diverse, highly decorative and, much to the surprise of newcomers, rarely religious.

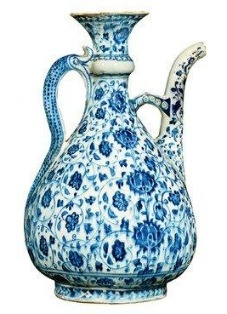

Iznik Ewer at Christie's |

Sharp price increases have occurred in Iznik pottery, made in western Anatolia from the 15th to the 17th centuries and colorfully painted in arabesques and other decorations. Prices for Iznik pottery are up 30% in the last five years, says William Robinson, Christie's international head of Islamic Art.

Still, the world auction record for Iznik pottery is a mere £616,000 (about $978,000), set at Sotheby's in April 1993, for a blue and white candlestick, dated 1480. This fall, Christie's is offering an Iznik ewer, circa 1510, estimated at £200,000 to £300,000. Simon Ray, a London dealer, is offering an Iznik flower vase, circa 1590, which is similar to one in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, for £65,000. Also at Christie's is a 17th-century Ottoman child's sword, with gold and pearls, estimated at £100,000 to £150,000.

Sotheby's is selling an important bowl, known as Mina'i ware, from the late 12th or early 13th century at an estimated price of £80,000 to £120,000; it is one of several pieces that the auction house is taking to Doha in mid-September to entice high-rollers in the Gulf.

American buyers are increasingly interested in Mughal works. Oliver Forge and Brendan Lynch Ltd. is offering a 17th-century illuminated Koran on gold-sprinkled paper for $30,000. Several experts cite opportunities in Egyptian and Syrian metalwork. And Mr. Robinson suggests looking at "quirky areas," like the 16th century Bukharan paintings that will be sold in October for the benefit of Oxford University. One, "Visit to a Dervish," is estimated at £100,000 to £150,000.

Before writing any checks, would-be buyers of Islamic art should be wary of two hurdles. As with all antiquities, provenance is important; a work that appeared outside its country of origin after 1970 is suspected of being illegally excavated under Unesco standards. Americans should also be careful not to run afoul of sanctions on trade with Iran.

—Judith H. Dobrzynski