New Haven

The first thing to know about "Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower: Artists' Books and the Natural World," an exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art here, is that it's misnamed. While the poetic first half works—the phrase comes from a 19th-century verse by William Gardiner—the second half is far too limiting. The exhibition presents prints, drawings, collages, specimen books, field notes, cut-paper objects, photographs, video, sound and multimedia pieces as well as books—plus some 18th- and 19th-century microscopes.

And while the show does draw inspiration from the naturalist categorizing and collecting craze captured in the title of Gardiner's 1846 book—"Twenty Lessons on British Mosses; Or First Steps to a Knowledge of that Beautiful Tribe of Plants"—it is far from the fusty show of botanical drawings that conjures.

"Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower" is instead an exuberant exploration of nature seen through the eyes of artists. A 1958 London Transport poster in the first gallery, portraying a boy, a girl and their dogs at the start of a country walk, embodies the show's spirit: Casually dressed, they take the wide path through a forest to a blue-sky adventure. This is going to be fun.

"Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower" is instead an exuberant exploration of nature seen through the eyes of artists. A 1958 London Transport poster in the first gallery, portraying a boy, a girl and their dogs at the start of a country walk, embodies the show's spirit: Casually dressed, they take the wide path through a forest to a blue-sky adventure. This is going to be fun.

And so it is, particularly in its first two-thirds. In organizing the show, Elisabeth Fairman, the museum's senior curator of rare books and manuscripts, leaned toward works by self-taught naturalists, especially women. Drawn mostly from the Yale Center's collections, plus some from other Yale institutions, the selection dates to the 16th century, but about half are contemporary, acquired in the past two decades. Ms. Fairman arranged them thematically, mixing works of different eras to create interesting juxtapositions. Sometimes, it's hard to tell which is which without reading the labels. And even when they diverge in style, the works share an aesthetic.

That point is illustrated by the two works that inspired the exhibition. One, the "Helmingham Herbal and Bestiary," c.1500, consists of drawings of animals, birds, flowers and trees as known in Britain's Tudor era. The other, "A Printmaker's Flora: An Anthology of the Names of British Wild Flowers," was published in 1996. Both are opened to pages depicting a blackberry bramble (the first artist unknown; the second, Rosaleen Wain) with true-to-nature color, simplicity and arrangement. They are kin.

The connection between traditional and modern, amateur naturalist and contemporary artist, is more direct in the case of Mandy Bonnell. Her spare but detailed drawings of "Wild Flowers Worth Notice" (2012) were inspired by a trove of floral specimens amassed in 1861 by one Miss Rowe. Competing for a "Botanical Prize" offered by the Liverpool Naturalists' Field Club, Miss Rowe collected 500 specimens, mounted them on paper, labeled them with their scientific names and placed them in blue envelopes—on which she painted watercolor images of what is inside, along with a printed botanical label. She placed them all in a mahogany box. Ms. Bonnell, who studied the center's collections, including Miss Rowe's treasure, produced her own cloth-covered box of similar pencil drawings on white paper. And as a nice touch, Ms. Fairman has placed nearby a copy of the 1861 field guide by Phebe Lankester, whose title "Wild Flowers Worth Notice" Ms. Bonnell adopted for her work.

A more loaded comparison links a different set of specimens mounted on paper, "collected by German botanist Gottlieb Wilhelm Bischoff (or colleague) somewhere in Europe before 1850," with the 2006 works of Tracey Bush, who fashions botanically correct collages from discarded paper wrappers picked up on the streets of London as a comment on the impact humans have on the environment. Her "Common Poppy," for example, contains such discernible brand names as Nestlé, Krispy Kreme, Lego and Reebok. Two other herbarium sheets from her "Nine Wild Plants" series—a dandelion and a buttercup—are nearby.

A more loaded comparison links a different set of specimens mounted on paper, "collected by German botanist Gottlieb Wilhelm Bischoff (or colleague) somewhere in Europe before 1850," with the 2006 works of Tracey Bush, who fashions botanically correct collages from discarded paper wrappers picked up on the streets of London as a comment on the impact humans have on the environment. Her "Common Poppy," for example, contains such discernible brand names as Nestlé, Krispy Kreme, Lego and Reebok. Two other herbarium sheets from her "Nine Wild Plants" series—a dandelion and a buttercup—are nearby.

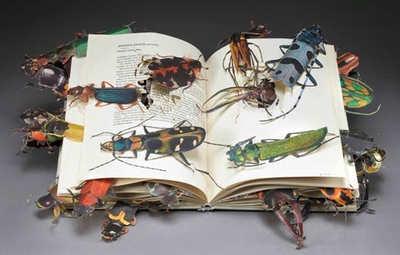

Other contemporary artists represented here may be making subtle points about the natural environment, but Ms. Fairman aimed to make this a visually enchanting, rather than a didactic, exhibit. On that score, one of the most intriguing objects has to be Julie Cockburn's vivid "Beetles Book" (2002) (above left). The attraction of this "altered book" is the paper beetles—large colorful creatures of varied kinds—that pop up from the pages, all but crawling out. Ms. Cockburn also delights with her "Flower Book: White Tea-Rose" (2005), a more benign work in which a large, pretty rose emerges, like a ladies' corsage, from the left side of an open book of poems.

Several other cutouts are also ingenious. From not all that far away, you'd swear that a paper basket (c.1820), embellished with watercolor flowers of blue, violet and red, edged in gold and stitched with silk thread, is porcelain. Sarah Morpeth has scissored two wonderful, three-dimensional landscapes: a hand-stitched, painted and bound work of paper twigs, leaves, flowers and fluttering butterflies called "A Garden Book" (2011) and "Crow Landscape" (2008), a blue paper thicket overflown by three black crows, attached with wire (at right).

Several works deploy feathers (and padding), with cut paper and watercolor, to make three-dimensional creatures—some from "Gould's Birds" (c.1865) and others from "Album of Bird Illustrations, Made from Feathers" (c.1880).

Several works deploy feathers (and padding), with cut paper and watercolor, to make three-dimensional creatures—some from "Gould's Birds" (c.1865) and others from "Album of Bird Illustrations, Made from Feathers" (c.1880).

Then there are the lyrical wood engravings of Sister Margaret Tournour, who died in 2003: Much like a latter-day Mrs. Delany, the 18th-century blue stocking who started making her gorgeous floral cutouts at age 72 (and who had an exhibition of her own here in 2009), Sister Margaret began focusing on wood engraving only in her late 70s, after retiring from teaching. Her highly detailed renderings of thistledown, teasel, dragonflies and other species are as keenly observed and composed as could be. They could have been made in the age of Dürer.

After galleries examining flora and fauna, when the exhibition shifts to "ponds and streams" and "country walks," it begins to lose focus and, well, charm. It ends with a gallery devoted to the work of Eileen Hogan, a British artist, inspired by Little Sparta, a Scottish garden created by poet and artist Ian Hamilton Finlay. Evocative of his single garden, and consisting of rather conventional watercolors, sketchbooks and poems by both him and her, it was a bit of a letdown.

There's one last thing to know about "Of Green Leaf, Bird and Flower." The galleries contain some 300 works of art, packed into a small suite. Since all of them can't possibly be taken in, this celebration of nature and naturalists is, fittingly, probably best approached by grazing. Go where your eye takes you.