In an age that favors large-scale installations and immersive art, when painting itself has been declared dead many times and, when practiced, is often judged to be hackneyed, the humble watercolor rarely figures at all in conversations about art.

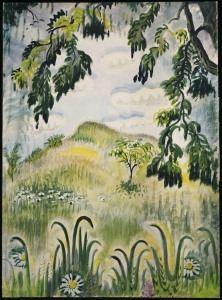

"Summer Benediction" |

How regrettable. Using watercolor paint, with its transparent quality and unruly fluidity, is treacherous and unforgiving—the opposite of easy. Unlike oil paint, it does not allow cover-ups of mistakes or midstream changes in design. Yet in the hands of masters, watercolors—as the summer exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum demonstrates—can deliver brilliant works that hold their own against art made in other mediums.

"Painting on Paper: American Watercolors at Princeton," a refreshing but uneven survey of 200 years of watercolors in the U.S., starts strong with a masterly work by Charles Burchfield, "Summer Benediction" (1948). Burchfield painted almost exclusively in watercolor, producing inventive views of his subjects—in this case, a dreamy landscape with white, yellow and pink wildflowers beneath a light blue sky and cumulus clouds, framed by the dark green leaves of an unseen tree that give the picture depth.

"Summer Benediction" conjures up a warm, lazy afternoon, hinting at the blessings of the earth, but is much lighter in tone than some Burchfield paintings, which are spiritual meditations with overt mystical or religious references. It is watercolor at its best—layers of color in assured brushstrokes and patches of unpainted paper that create highlights. This luminous image, then, neatly leads to the exhibition's introduction, a short primer on the technical aspects of the medium.

A text explains how artists use finely ground pigment in a gum arabic solution that yields that transparency, and how they pile up washes to turn light colors into dark, all the while avoiding the bleeding of one color into another. Along with pure watercolors, artists may use gouaches, made with the same pigment but incorporating white chalk or paint; but with gouaches, artists apply dark colors before adding successively lighter ones to produce opaque, matte works. Two pictures here illustrate the difference: John James Audubon's delicate watercolor, "Yellow-Throated Vireo" (1827), and Morris Graves's gouache, "Antelope" (1930-39).

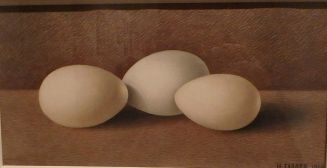

"Three Eggs" |

Mary B. Tucker, who is thought to have worked near Concord and Sudbury, Mass., likely painted an early gem, for example, the unsigned "Girl in Calico" (c. 1840-1850). In a half-length portrait, a serious young girl exhibits pellucid skin, wears her long hair in perfect sausage curls, holds a book, and stares at the viewer with almond-shaped eyes. Her dress, with stripes made of brown and blue daubs, flows from the artist's brush a bit less fastidiously, a common practice in portraiture of the times.

Contrast that with the charming baby picture "Mehitable Eddy ("Hetty") Taber" (1830) by the less accomplished Deborah Smith Taylor (1796-1879). In her folksier style, the child is dressed in a meticulous bare-shouldered, full blue dress, but her head and hair are sketchier and the artist lets the woven paper stand in for flesh.

Before too long, watercolors had evolved to allow more ambitious works, such as the marvelous little "Three Eggs" (1868) by Thomas Charles Farrer. A British-born follower of John Ruskin's diktat—to be "true to nature"—Farrer renders perfectly modeled eggs, of slightly different sizes and shapes, on a plain beige counter against a plain tan background, both formed by tiny visible brush strokes. Bare simplicity is rarely so beguiling.

"Eastern Point Light" |

Here, Homer employs several techniques to go beyond the ordinary. To make his haloed white moon, he probably scraped the paper clean with a knife (or thumbnail). To create the reflection of moonlight on the water (and texture), he gouged out damp blue pigment with the end of his brush. At times, he probably used a fairly dry brush to spread pigment quickly and unevenly, allowing bits of white to show—in the stars, for example.

This exhibit is flawed, though. Because the works on view are mostly drawn from the university's own collections, some masters of the medium are present with weak pictures. I longed to see one of Charles Demuth's flower or architecture watercolors, for example, instead of his sketchy "Trees, No. 2" (1916), and for better works by Prendergast, Arthur Dove, John LaFarge and a few others. Nonetheless, "Painting on Paper" is gratifying, its shortcomings offset by the very fact that it exists.