Brunswick, Maine

A rainbow-striped canvas; an exercise bike equipped with a horn, a basket and a sweatshirt; six photographs of a tree against the sky. You may think of portraits as paintings, photographs or sculptures that capture the physical likeness, especially the face, of a person, which is the dictionary definition. Yet at "This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today"—which includes those artworks by Ross Bleckner, Eleanor Antin and Alfred Stieglitz, respectively—there is nary a face in sight.

The galleries here at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art are instead filled with more than 60 conceptual, symbolic and abstract works—attempts by modernists to go beyond the appearances captured so well by photography to a subject's identity, achievements and personality.

The galleries here at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art are instead filled with more than 60 conceptual, symbolic and abstract works—attempts by modernists to go beyond the appearances captured so well by photography to a subject's identity, achievements and personality.

The show's title refers to a famous incident that took place in 1961, when Parisian dealer Iris Clert invited avant-garde artists to submit a portrait of her for an exhibition. Robert Rauschenberg, working in Sweden, forgot about the request; at the last minute, he sent a playful telegram to the gallery saying, "This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so."

That telegram opens the exhibit, but Gertrude Stein actually gets the ball rolling with her experimental text portrait " Pablo Picasso" (1909, published in Camera Work in 1912). It begins "One whom some were certainly following was one who was completely charming" and carries on in the same convoluted vein for two pages, devoid of physical description and repetitive but, it must be admitted, not a bad characterization of Picasso.

From there the exhibition moves in several directions. Taking note that "non-mimetic" portraits progressed in fits and starts, it focuses on three fertile periods—the 1910s and 1920s, the early 1960s to 1970 and the early 1990s through today—with a section devoted to each.

The first and most familiar time frame blooms with a few well-known paintings like Marsden Hartley's "One Portrait of One Woman" (1916)—an amalgam of references to Stein like a tea cup symbolizing her hospitality and the red-white-and-blue of both the American and French flags—and Gerald Murphy's "Razor" (1924), a self-portrait featuring objects, like a pen, closely associated with him. Charles Demuth, whose renowned poster portraits include the masterly "The Figure 5 in Gold" rendering of William Carlos Williams, is here represented by studies for three others in the series, of Hartley, Arthur Dove and Wallace Stevens.

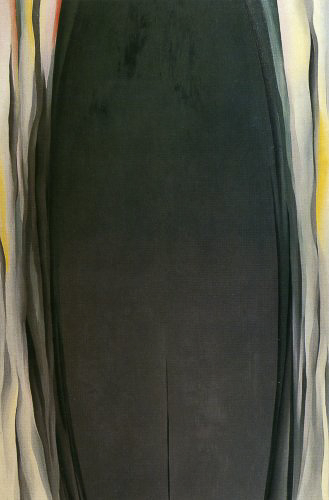

Most other works are more conceptual. For example, Virgil Thomson's melody "Portrait of Florine Stettheimer" (1941), which he composed "from life" in the presence of the artist who designed the sets for the opera he co-wrote with Stein, "Four Saints in Three Acts." In "Georgia O'Keeffe," a book published in 1976 and open to "Green-Gray Abstraction" (1931), O'Keeffe suggests that among her many abstract paintings are portraits. "I have painted portraits that to me are almost photographic. . . . But they have passed into the world as abstractions—no one seeing what they are," she writes on the facing page. Stieglitz's upward-glancing gelatin prints, "Portrait—K.N.R., No. 1-6)" (c. 1923), purportedly capture the painter-poet Katharine Rhoades.

O'Keeffe's Green-Grey Abstraction |

Bowdoin addresses this issue by providing long explanatory labels for every work of art, with some running to more than 200 words. They are helpful, but not always enough.

In a curious way, the problem abates in the final section as artists lean toward showing group, gender and racial identity, rather than individuality. Mr. Blechner's rainbow canvas, "Double Portrait (Gay Flag)" (1993), speaks to his overwhelming identification as a homosexual, with a tiny nod to his Jewishness visible in a small Star of David near the top of the canvas. Byron Kim delivers a group portrait, "Synecdoche" (1991-present), consisting of small rectangles, each painted with the skin tone of the person portrayed.

Many of these efforts are aided by technology. Inigo Manglano-Ovalle's "Byron, Lisa, and Emmett" (1998) uses autoradiographs to determine DNA patterns, then scans and colors them, with the collaboration of the subjects, to make chromogenic prints of their genetic material. And Jason Salavon, in a video projection, "Spigot (Babbling Self-Portrait)" (2010), suggests that he is the sum of his Google searches.

Clearly, this was a risky exhibition: Aside from its intellectual basis it's not, with some exceptions, very visually appealing. But Bowdoin deserves credit for being the first museum to focus solely on the evolution of these works in the U.S., especially in a populist era in which museums are aiming for large attendance rather than large ideas. Visitors who spend time in "This Is a Portrait If I Say So" will find it to be a valuable learning experience.