Brooklyn, N.Y.

Fridalandia! The vast exhibition that just opened at the Brooklyn Museum is officially titled "Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving," but a more apt moniker might have paralleled what she called the U.S.: Gringolandia. This display of more than 325 objects, from photographs to clothing to orthopedic corsets to lipsticks and eyebrow pencils, takes visitors on a trip through Kahlo's world, from her comfortable childhood to her tormented medical history to her troubled marriage with renowned painter Diego Rivera to her complicated identity. It is all things Frida. It's a three-dimensional scrapbook. It even includes the prosthetic leg, in a boot, that she wore after her leg was amputated.

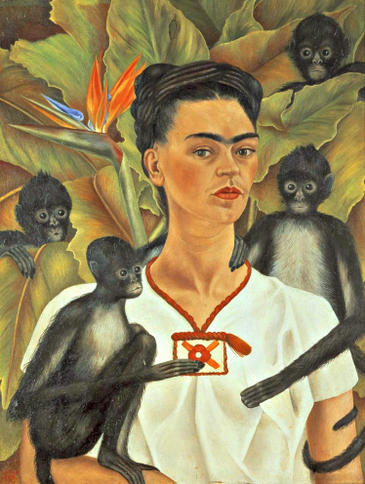

Self-Portrait With Monkeys |

The Brooklyn exhibition does not advance her narrative, but it does add texture with newly available personal artifacts. When Kahlo (1907-1954) died, Rivera (1886-1957) locked up a large trove of her personal belongings in Casa Azul, her lifelong home in Mexico City, stipulating that they could not be seen until 15 years after his death. But they weren't even inventoried until 2004 and weren't shown much outside Mexico until last year's exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Brooklyn has expanded that show, mixing in more photographs, archival materials, three additional paintings, and Mesoamerican works that resemble those Kahlo and Rivera owned.

Muray's Frida on Bench |

Soon after the accident, Kahlo began painting, and she awakened to social conditions in a Mexico emerging from revolution. She started wearing indigenous clothes—a shawl, lace outfit and a few other pieces shown here—and she met and married Rivera. With his doodles to her (from 1939), photographs of the pair, and other artifacts, visitors see their love, their anger, their Communist leanings and their travels in the U.S., where she adores New York and San Francisco, but loathes Detroit. In a 1932 lithograph of her injured body, she broods over a miscarriage there.

One of her costumes |

The exhibition ends in a flourish, with about 20 of her costume ensembles. She composed these colorful mixtures of long, ruffled skirts, embroidered blouses, and flowing shawls as carefully as her paintings.

But here's a question: What would Frida think? Kahlo has certainly come a long way from the time when a Detroit newspaper headline called her the "wife of master mural painter" who "gleefully dabbles in works of art." Yet this exhibit includes just 11 paintings by her, and only three are notable. The arresting "Diego on My Mind (Self-Portrait as Tehuana)" (1943) depicts her in the starched white headdress worn by women of Tehuantepec, with a portrait of Rivera on her forehead as a telltale sign of their troubled relationship. In "Self-Portrait With Monkeys" (1943), one of the four wide-eyed black

A plaster corset |

This engaging and sometimes engrossing exhibition will delight Kahlo fans, but for me it's a missed opportunity to dilute the fixation on her biography and engage them with more of her path-blazing, idiosyncratic art. The balance between her life and her art is, as ever, askew.