Los Angeles

In the past several years, unicorns have become ubiquitous. Evoking radiant rainbows and beguiling dreams, these elusive and magical beings have been used to sell cuddly toys, movies, makeup, pajamas, videogames and high-tech companies with aspirations of grandeur.

So that is where the J. Paul Getty Museum has chosen to begin its exhibition "Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World." The first gallery is filled with such items as a German parade saddle made of bone and carved with a unicorn (c. 1450); a fine linen embroidery of a unicorn hunt (c. 1370-1400), also from Germany; and a Swiss tapestry (c. 1480) with a unicorn as a central character—as well as the richly decorated Ashmole Bestiary (c. 1210-20) opened to a unicorn page.

So that is where the J. Paul Getty Museum has chosen to begin its exhibition "Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World." The first gallery is filled with such items as a German parade saddle made of bone and carved with a unicorn (c. 1450); a fine linen embroidery of a unicorn hunt (c. 1370-1400), also from Germany; and a Swiss tapestry (c. 1480) with a unicorn as a central character—as well as the richly decorated Ashmole Bestiary (c. 1210-20) opened to a unicorn page.

But the unicorn gambit was hardly necessary. Plenty of other fascinating wild beasts—both real (tigers, antelopes, pelicans) and imaginary (griffins, dragons, bonnacons)—run rampant through the galleries. Curated by Elizabeth Morrison with Larisa Grollemond and said to be the first major museum exhibition on bestiaries, "Book of Beasts" presents, along with more than 30 medieval bestiaries, about 100 other manuscripts and objects inspired by them, including several contemporary artworks in the final gallery. It offers some surprises for pop culture devotees of the unicorn (and the rest of us, too) and explains how these engaging books have affected common conceptions even today.

Bestiaries were like animal encyclopedias, but with a higher purpose: Created by inventive artists and scribes, they were intended to enkindle in readers awe for the natural world and to impart religious stories and moral allegories. Those unicorns, for example, actually symbolize Christ. They are frequently seen leaping into the lap of a maiden, the Virgin Mary, and their subsequent capture and killing represents the redemption of mankind.

Bestiaries were like animal encyclopedias, but with a higher purpose: Created by inventive artists and scribes, they were intended to enkindle in readers awe for the natural world and to impart religious stories and moral allegories. Those unicorns, for example, actually symbolize Christ. They are frequently seen leaping into the lap of a maiden, the Virgin Mary, and their subsequent capture and killing represents the redemption of mankind.

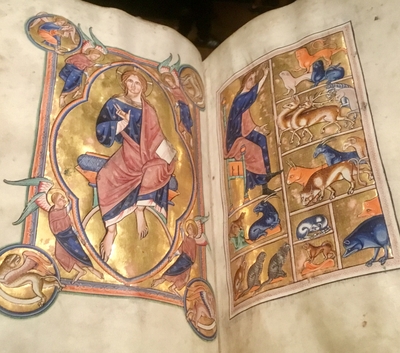

The exhibit's heart beats in the second gallery, where the Getty has showcased about two dozen of these seminal texts, including the famed Aberdeen Bestiary (c. 1200) [top right], Rochester Bestiary (c. 1230-50) and its own Northumberland Bestiary (c. 1250-60). The Aberdeen Bestiary, a highly colored, heavily gilded manuscript, is open to a spread showing Christ on the left while, on the right, Adam names the animals, as related in Genesis.

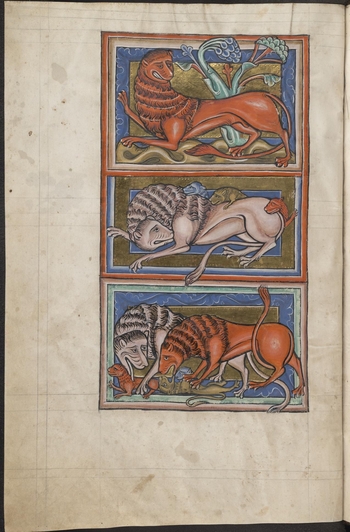

Nearby, an English bestiary (c. 1250) is open to a page depicting a lion, which always comes first in bestiaries and is called "rex." That is why we call the lion the king of beasts. Bestiaries also disseminated the notions that foxes are wily, that elephants remember well, and that dogs are loyal, among other animal lore.

This English manuscript portrays the lion in three guises [lower left]: covering its tracks with its tail, sleeping with open eyes, and breathing life into its young. That last image relates to the Resurrection. People then believed that cubs were born dead, but given life by their fathers after three days. That same image recurs again at the bottom of a page from a German missal (before 1381) whose main image portrays the Resurrection.

This particular English lion looks more like a weasel, while the German one seems more accurate. But bestiary illuminators probably never saw most of the animals they were drawing, and weren't striving for accuracy anyway. They used their imagination, sometimes with amusing results. That strange brown, snub-nosed, long-tailed animal with a green mane in another English bestiary (c. 1230), for example? It's a hippopotamus.

This particular English lion looks more like a weasel, while the German one seems more accurate. But bestiary illuminators probably never saw most of the animals they were drawing, and weren't striving for accuracy anyway. They used their imagination, sometimes with amusing results. That strange brown, snub-nosed, long-tailed animal with a green mane in another English bestiary (c. 1230), for example? It's a hippopotamus.

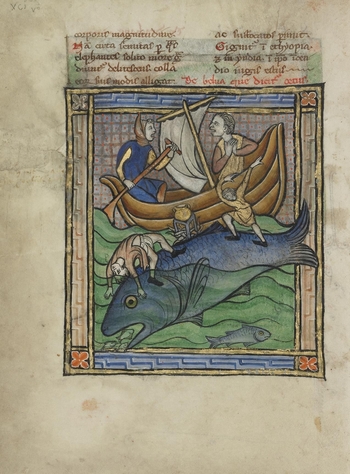

In one French bestiary (c. 1270), a calm, blue whale—which, like the one that swallowed Jonah, sometimes symbolizes the devil—contrasts with the crazed seamen on its back: The painter captures the very moment those sailors realized they had landed their ship on the whale, not an island [top left]. But if the Ashmole bestiary were open to its whale page—the Getty has provided a copy of the image—visitors would see a bold, far more stylized gray whale swallowing a man.

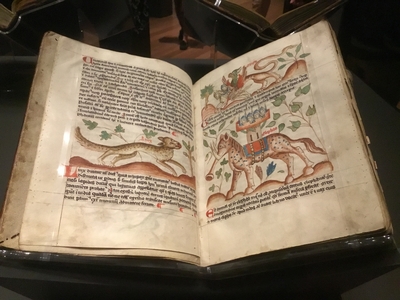

Sometimes the illustrators play with the pictures, drawing animals that make eye contact with one another or slither through a page of text. In the Salvatorberg Bestiary (c. 11375-1400) [lower right], a lynx seems to stick out its tongue at the griffin and elephant on the opposite page, the label suggests. With such enchanting images, there's little wonder that these books have worn and soiled edges: Among the wealthy, literate classes, they were prized for both religious and entertainment value.

Bestiaries, popular mostly in Northern Europe, started fading out after about 1300, subsumed into broader natural history texts and encyclopedias. But their fantastic imagery lived on. Their wide and lasting impact is here manifest in an Islamic water vessel in the form of a cheetah (c. 1000-1300); a Scottish book about heraldic images called "Deeds of Armory" (c. 1494); Hans Hoffmann's beautiful, finely detailed painting "A Hare in the Forest" (c. 1585); Picasso's aquatint "Eagle" (1936) in a French natural history book; and Walton Ford's forbidding "Grifo de California" (2017), a large gouache/watercolor that replaces the traditional griffin hybrid of lion and eagle with a locally appropriate mix of California condor and cougar.

Bestiaries, popular mostly in Northern Europe, started fading out after about 1300, subsumed into broader natural history texts and encyclopedias. But their fantastic imagery lived on. Their wide and lasting impact is here manifest in an Islamic water vessel in the form of a cheetah (c. 1000-1300); a Scottish book about heraldic images called "Deeds of Armory" (c. 1494); Hans Hoffmann's beautiful, finely detailed painting "A Hare in the Forest" (c. 1585); Picasso's aquatint "Eagle" (1936) in a French natural history book; and Walton Ford's forbidding "Grifo de California" (2017), a large gouache/watercolor that replaces the traditional griffin hybrid of lion and eagle with a locally appropriate mix of California condor and cougar.

"Book of Beasts" demonstrates well how an esoteric subject can appeal to the general public without stooping to conquer, without losing its scholarly approach. It shows the bestiary to be a wondrous thing.