San Marino, Calif.

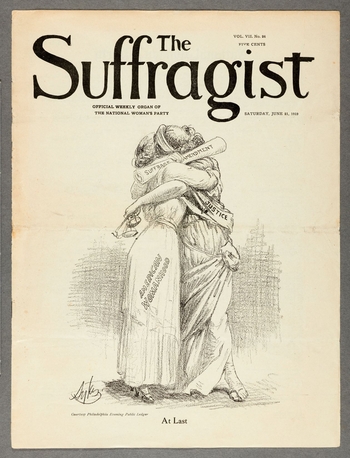

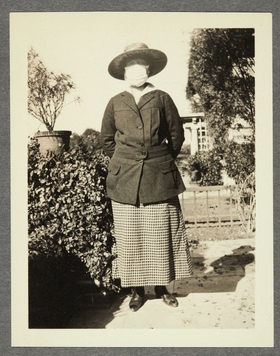

Ben Franklin's handwritten autobiography open to a spread with a giant splotch of brown ink. A poster from the 1919 German Revolution warning "Crowds of rioters will be indiscriminately shot." A June 21, 1919, issue of the Suffragist marking the Senate's passage of the 19th Amendment. A first-edition print of the Treaty of Versailles showing Europe's new boundaries. Photos of Pasadenans wearing surgical masks during the 1917-19 flu pandemic.

These disparate items, and about 260 more, fill the special exhibition galleries of the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in "Nineteen Nineteen."

These disparate items, and about 260 more, fill the special exhibition galleries of the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in "Nineteen Nineteen."

That was the year that railroad and real-estate magnate Henry E. Huntington and his wife, Arabella, signed the trust agreement creating the Huntington as a public institution. A centennial exhibition was clearly in order. But curators James Glisson and Jennifer A. Watts chose to avoid the obvious—chronicling the institution's history. They decided instead to show what the world was like during that "cataclysmic" year, full of revolution, recovery, redrawn national borders and struggles for human rights.

This fresh approach celebrates the wealth of the Huntington's collections but also exposes their idiosyncratic nature, which was determined by the interests of its founders and subsequent directors and donors. Even drawing from its 11 million objects and using the broadest parameters—selecting items that were made, published, exhibited, edited or acquired in 1919—the curators could not create a full portrait of a year that included the ratification of Prohibition, the Russian civil war, the Amritsar Massacre, the Black Sox Scandal and the race riots and lynchings of the "Red Summer," to name a few events that had to be omitted (except in the blown-up newspaper clips that provide a backdrop to the display).

Still, they delivered an exhibition as surprising, intriguing and, well, frenetic as the year itself.

Perhaps the first surprise is that almost none of the items here were bought by the voracious Huntingtons—1919 turned out to be a "pause" year in their collecting. To give Huntington his due, there is, at the heart of the show, a partial re-creation of an exhibition of 35 treasures he staged for the New York Author's Club in 1919 at his Gilded Age mansion on Fifth Avenue: three portraits of George Washington, including one by Gilbert Stuart (1819); a copy of the first Bible printed in North America (1661), which was also the first in a Native American language; the original handwritten minutes of George III's secret cabinet discussions about American independence (1782-83); and Franklin's blotted manuscript (1771-89), among them.

Perhaps the first surprise is that almost none of the items here were bought by the voracious Huntingtons—1919 turned out to be a "pause" year in their collecting. To give Huntington his due, there is, at the heart of the show, a partial re-creation of an exhibition of 35 treasures he staged for the New York Author's Club in 1919 at his Gilded Age mansion on Fifth Avenue: three portraits of George Washington, including one by Gilbert Stuart (1819); a copy of the first Bible printed in North America (1661), which was also the first in a Native American language; the original handwritten minutes of George III's secret cabinet discussions about American independence (1782-83); and Franklin's blotted manuscript (1771-89), among them.

The rest of the items in "Nineteen Nineteen" match five loose themes: Fight, Return, Map, Move and Build. Many objects amaze because they are unexpected: mug shots of German "alien enemies" jailed in Los Angeles because of the war; charmingly illustrated sheet music for songs like "Let the Rest of the World Go By"; and panoramic photographs from a privately printed book detailing a trip made in 1919 by 12 male friends intent on seeing the West—among them, Orville Wright. They drove three Cadillacs and a Packard from Denver to California, mostly over dusty, unpaved roads, bringing along down sleeping bags and the "Official Automobile Blue Book," a copy of which is nearby.

The more expected items are equally intriguing. Huntington was instrumental in the development of Los Angeles—he made his money in real estate—and visitors will find such items as detailed maps of the regional trolley lines; electric company documents and photographs; a Toucan brand citrus-crate label from Huntington's agricultural interests; and specimens of plants that would have grown in the gardens in 1919.

The more expected items are equally intriguing. Huntington was instrumental in the development of Los Angeles—he made his money in real estate—and visitors will find such items as detailed maps of the regional trolley lines; electric company documents and photographs; a Toucan brand citrus-crate label from Huntington's agricultural interests; and specimens of plants that would have grown in the gardens in 1919.

There's a vitrine of rather ordinary books, as well as a handmade copy of Virginia Woolf's short story "Kew Gardens," which contains two woodcut illustrations by her sister Vanessa Bell and covers painted by Roger Fry and Duncan Grant.

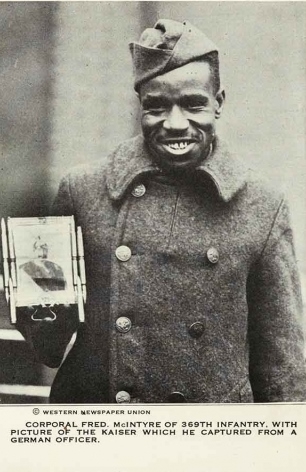

As for the freneticism, that feeling stems from the busy display that jumps from one topic to another. Next to those frightening German Revolution posters is a devastating World War I print, "Birdseye View of Ypres," the Belgian town reduced to a "ghastly ruin" in battles. A few feet away, just beyond two books describing the role of African-Americans in World War I is a rare copy of "The Negro Trail Blazers of California," which documents the contributions of African-American pioneers to California's development.

Elsewhere, the flu pictures hang not far from a row of poignant photographs of French children, often holding hands, orphaned in the war and later supported by the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena. T.E. Lawrence's autograph album from the 1919 Paris Peace Conference—signed by the likes of David Lloyd George —faces a wall of photos of spiral galaxies, star clusters and the moon taken through Mount Wilson's reflector telescopes.

Elsewhere, the flu pictures hang not far from a row of poignant photographs of French children, often holding hands, orphaned in the war and later supported by the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena. T.E. Lawrence's autograph album from the 1919 Paris Peace Conference—signed by the likes of David Lloyd George —faces a wall of photos of spiral galaxies, star clusters and the moon taken through Mount Wilson's reflector telescopes.

While head-spinning, this frenzy doesn't diminish "Nineteen Nineteen." It actually gives visitors a sense of living through such a turbulent year, which has some parallels with today. It may also send them to the exhibit's indispensable catalog for more information—or, to a library.