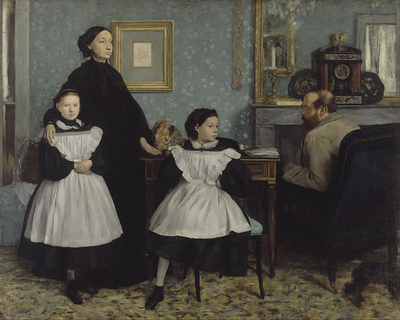

It's called "The Bellelli Family" or simply "Family Portrait," but neither title does the painting justice. Begun by Edgar Degas in August 1858, likely finished the following year, and revised around 1867, the large canvas is actually a complex, unusually candid depiction of the tensions, emotions and alienation within a nuclear family. Had this breakthrough work been well known before Degas died in 1917—when it was still in his possession—he might be just as renowned today for this youthful triumph as he is for the brilliant pastels of ballet dancers from his mature years.

Degas was just in his 20s when he painted "The Bellelli Family," but its size—6 1/2 feet by 8 feet—signals his ambitions for it. The woman in the frame is his beloved Aunt Laura, his father's sister, and he was living with the Bellellis in late summer 1858. Her husband, Gennaro, had been exiled from their home in Naples because of his political activities in the 1848 revolution, and the family had moved to Florence. They were living in furnished rooms, with all the accoutrements of middle-class life: a mantel clock, a candlestick, gilt-framed mirror, paintings, chandelier and bell pull. But it was not a happy home. In letters to Degas, Laura calls her husband "disagreeable" and "detestable."

Degas was just in his 20s when he painted "The Bellelli Family," but its size—6 1/2 feet by 8 feet—signals his ambitions for it. The woman in the frame is his beloved Aunt Laura, his father's sister, and he was living with the Bellellis in late summer 1858. Her husband, Gennaro, had been exiled from their home in Naples because of his political activities in the 1848 revolution, and the family had moved to Florence. They were living in furnished rooms, with all the accoutrements of middle-class life: a mantel clock, a candlestick, gilt-framed mirror, paintings, chandelier and bell pull. But it was not a happy home. In letters to Degas, Laura calls her husband "disagreeable" and "detestable."

Degas chose to portray a moment soon after the death in Naples of his grandfather, who is commemorated in the red chalk drawing hanging behind Laura's left shoulder. Laura and her two daughters, having just returned from Naples, wear the black garb of mourning. The trio forms a loose grouping that occupies two-thirds of the canvas, with the younger girl, Giulia, at the center.

Detail |

That physical separation merely begins this family psychodrama, in which every member has a role. Laura looks away, into the distance, her eyes fixed on something unknowable, or perhaps simply in avoidance of her husband. She is thought by some scholars to be pregnant (with a boy who dies in infancy), and she steadies herself with one hand on the desk. Her face is stern.

Laura's right arm rests protectively on the shoulder of the older girl, Giovanna, who stands upright, stiff as an I-beam, with her feet together, her hands folded at her waist. Aligned obediently with her mother, she is the only character who meets the viewer's gaze, but those eyes express some uncertainty. She seems to be caught uncomfortably in a position that's not necessarily to her liking.

Giulia, on the other hand, was the more free-spirited of the girls, and Degas portrays her in a more playful pose, with her leg crossed under her dress and her arms akimbo. Giulia was closer to her father, though here she seems either conflicted or, as some scholars suggest, indifferent to the troubles. Pulled in opposite directions by her parents, she casts her gaze away from the room, refusing to meet his glance. She is striving for a measure of autonomy, with her position on the edge of the chair suggesting her impatience to get away from the turmoil.

Gennaro, busy at his desk, seems stubbornly withdrawn from his family, a separate entity. Degas suggests him as the disruptive force—he reportedly disliked him—by placing his chair at an angle, a departure from the geometry of the rest of the painting, with one exception. A diagonal, extending from Laura's nose, down her right arm, across Giulia's white pinafore, points to the rear of a little dog, leaving the room, in the lower right corner. He seems to be escaping the palpable tensions.

As if these elements were not enough, Degas adds to the feeling of unease with his portrayal—or lack thereof—of legs, human and otherwise. Neither Laura nor Gennaro seems to have any. Giulia sits clumsily on one leg and steadies herself, unnaturally, with the other. Giovanna has two feet, but on first glance only one is visible. Some legs on Gennaro's chair and desk also appear to be missing.

Degas made many sketches for the painting and changed his mind after starting it too. Originally, for example, Gennaro wasn't in the painting at all; then he was, but sitting at the desk, not set away from it.

Detail |

Later in his life, when he moved, he placed it along with other large paintings in storage with his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, who exhibited it after Degas died. There, his friend Mary Cassatt saw it, and advised her friend, the great collector Louisine Havemeyer, to buy it. Cassatt also brought it to the attention of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which wanted it.

But neither was to be: The French government swept in almost immediately and purchased the painting, eventually passing it to the Musée d'Orsay. There, the painting, a milestone in capturing the dynamics of complicated relationships, occupies a place of honor, hanging for all to see on a wall that is clearly visible from the museum's central allée.