Hartford, Conn.

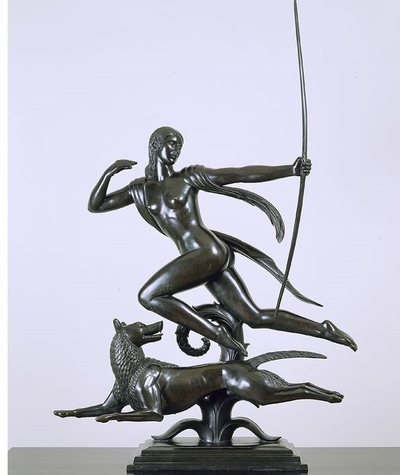

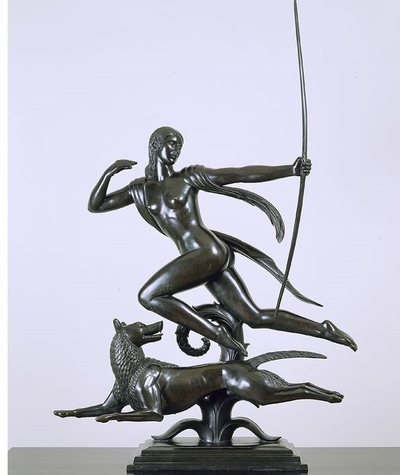

One early piece in the exhibition " Paul Manship : Ancient Made Modern" at the Wadsworth Atheneum is a stunner, but not for the usual reasons. "Centaur and Mermaid" (1909) is a small, dull, lumpy piece of electroplated plaster. It is the polar opposite, artistically, of a pair of works near the end of the show, "Diana" and "Actaeon" (1925). They are dynamic bronze sculptures of the mythical pair with a powerful presence and dazzling patinas.

Diana |

The path Paul Manship (1885-1966) took from one to the other forms the spine of this exhibition. Though long since overshadowed by abstract and later sculptors, Manship was for a time in the early decades of the 20th century the most important and popular sculptor in the U.S. Whether they know it or not, many people, especially residents and tourists in New York, have admired his works, which include the monumental gilded "Prometheus" (1934) at Rockefeller Center; the "Group of Bears" (1932, cast 1963) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and the "Rainey Memorial Gates" (1934) that include lions, tortoises and bears at the Bronx Zoo.

In other words, this exhibition reveals how Manship became Manship, how he melded his interests in ancient art and mythological tales with early 20th century sensibilities to make something new, a style that bloomed into Art Deco.

Born in St. Paul, Minn., Manship had studied art there, in Philadelphia and in New York when in 1909 he won the prestigious Rome Prize, with a three-year residency, from the American Academy in Rome. There, he imbibed the Renaissance and classical traditions of Italy, Greece and Egypt, and began to transform his art.

Actaeon |

By 1912, he had made "Lyric Muse" in polished bronze—far better than that 1909 piece, but still a somewhat awkward kneeling pose for his subject. Another work, "David" (1914), made back in New York, also disappoints. As the label notes, creating a David was a rite of passage for a sculptor, and Manship's rather flat David, with his odd head and barely visible slingshot, is a slender achievement.

Then comes "Centaur and Dryad" (modeled 1913, cast 1925), designed in the year that seems to be something of a turning point. It captures the moment when the half-man, half-horse beast clutches at the fleeing wood nymph. Keeping Greek and Renaissance sculpture in mind, Manship adds his own stylized elements in, for example, the dryad's ribbed hair and flowing gown. He displays his penchant for patterns and decorative details in the ivy-strewn ground beneath the duo and the elaborate, low-relief frieze of drunken satyrs and dancing women on the pedestal. This is the Manship that has fame within reach.

Fire |

Visitors can see this progress as they view Manship's sculptures alongside examples of ancient objects like those he probably saw, such as a red-figure Greek vase (c. 525-10 B.C.) and an Assyrian relief panel from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II (883-59 B.C.). Drawings illustrate how he later applied these studies in the studio. The ornamental elements of "Frieze Detail From Treasury of Siphnians, Delphi" (1912), for example, influenced the pedestal of "Centaur and Dryad," and the curves of the plant in that same drawing turn up in the stalks he incorporated into "Diana" and "Actaeon."

The exhibition reaches its peak with two large-scale installations. In 1914, Manship was commissioned to provide decoration for the neoclassical Greek headquarters of AT&T in Manhattan's Financial District; he created four bronze, partially gilt panels depicting Earth, Fire, Wind and Water—each one almost 5½ feet long. When AT&T decided around 1980 to decamp to a new building, it took down the "The Four Elements" and replaced them with replicas; the originals (now in private hands) hang here.

Water |

Densely ornamented, "The Four Elements" embody what the exhibition curator, Erin Monroe, calls the "mashup" of Manship's style—a blend of Renaissance, classical and South Asian styles. "Earth" is a bare-breasted, crowned woman with an Indian profile, at rest with fruits and animals; "Water," also a supple nude woman but with classical features, holds a ship and a Greek trident while riding a dolphin through a foamy sea. "Fire" and "Wind" are personified by muscular male nudes, one holding a torch and the other aloft in the clouds. Each includes typical Manship traits—stylized elements (the hair, for example), repeated patterns (in the flames, the birds' wings, on the borders), and movement or, at least, drama.

And then there are his brilliantly composed "Diana" and "Actaeon." She, having been surprised while she was bathing, has fired her arrow at him, turning him into a stag. They run in opposite directions, their graceful bodies in midair. With their strong lines, they are superbly crafted, another Manship hallmark.

Pronghorn Antelope |

"Paul Manship: Ancient Made Modern," on view through July 3, doesn't cover his entire career. Of his many animal sculptures, for example, only two, "Pronghorn Antelope" (1914) and "Great Horned Owl" (c. 1932), are here. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the owl is the latest work in the exhibition. By the 1940s, Manship was seen as lacking in imagination—relegated to the Art Deco era. But that shouldn't diminish appreciation for the many beautiful sculptures he did create, no small achievement.