San Francisco

Pompeii beckons. Frozen in time when it was engulfed in volcanic ash and debris from Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, then rediscovered in 1748, this ancient Roman town has fascinated the public ever since. Before the pandemic intervened, tourists were limited to 15,000 at a time, lest the site be overrun; now reopened, it is selling timed tickets and keeping attendance even lower.

Bacchus, A.D. 50-150 |

The curious, however, may be partly sated at the Legion of Honor of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, where "Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave" is on view through Aug. 29. With about 150 objects—from life-size marble sculptures and room-size garden frescoes to toothpicks made of bone and lentils carbonized by the 550-degree-plus heat of the eruption—the exhibition zeroes in on the eating and drinking culture of Pompeii. It's drawn from a larger 2019-20 show at Oxford University's Ashmolean Museum; but it has been slimmed down to eliminate duplicate utensils and a section on Roman Britain, and beefed up to add more art objects, such as a dining couch (first century A.D.) from the site and a fetching, ivy-wreathed bronze head of Bacchus (first half, first century A.D.) borrowed from the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Bacchus, the god of wine and fertility, hovers over this exhibition, a sign of his importance in the daily life of Pompeians. He's gloriously imposing as a six-foot marble statue at the entrance (A.D. 50-150), his companion panther at his side. (Like some other pieces in the exhibition, this Bacchus was not actually found at Pompeii, but is representative of the time and place.) He's amusing, cloaked in grapes like an ancient Bibendum, offering wine to his panther, in a fresco (A.D. 60-79) that once was part of a household shrine. He's intent, pouring wine from an amphora, in a three-foot bronze (first century A.D.). He's present symbolically, as a panther, in a one-footed marble table that likely graced the atrium of a wealthy Pompeian home.

Mosaic, 100-1 B.C. |

And where Bacchus is not present overtly, his spirit dominates: The items on display project a sense of conviviality, abetted by bountiful food and drink. In the first gallery, a small fresco (A.D. 40-79) portrays a group of women at a dinner party, with the central figure doling out wine to friends who have already imbibed quite a bit. Later, and more typically, there's one (A.D. 40-79) showing men and women reclining on couches to dine. This party is even more revelrous—in the Latin scrawled on the wall, a woman announces that she's going to sing, and a male guest shouts, "Yes, you go for it!" (as translated in the excellent Ashmolean catalog).

"Naughty" fresco, 30 B.C.-A.D. 79 |

Other objects depict what Pompeians, gifted with a fertile setting, ate. A splendidly complex mosaic (100-1 B.C.) is a mélange in tiny, fine tesserae illustrating marine life, probably fished from the nearby Bay of Naples: squid, eel, lobster, octopus, grouper, seabass and more. A vivid fresco (first to second century A.D.) depicts two men (probably slaves), dressed in white, preparing a calf, or deer, for a banquet: One slices its belly, while the other steadies the animal. And along with those burnt lentils, there are carbonized figs, dates, walnuts, almonds, pomegranates, grapes, plums, olives, beans, sea urchin, oyster shells, millet, wheat and, finally, an intact round loaf of bread, all turned into charcoal by that fateful eruption. Above the bread, a fresco (A.D. 40-79) shows a wealthy man giving bread to the less fortunate.

Garden Room frescoes |

Ah, but there's a subtext to that picture, hinting at the Roman sense of humor. Those in the know would realize that man had "carefully timed" his bread distribution to take place "just before the election of town officials," according to the label. And Pompeians would surely understand that a lovely still-life fresco (A.D. 45-79) showing a cockerel pecking at a pomegranate signaled that he would soon be stuffed with pomegranates or served in pomegranate sauce. Depicting an animal with its impending culinary fate was common.

Fresco, still life, A.D. 45-79 |

Like Bacchus himself, Pompeians had a licentious side, here resulting in a split in the exhibition path. The wary bear to the right to see glass, bronze and ceramic vessels and cookware, including a bronze food mold shaped like a chicken (A.D. 1-79). The adventurous go to the left into a "naughty" section filled with erotica found in homes, public baths and brothels. A few items are tame, like a handsome fresco depicting a satyr cupping the breast of a maenad (30 B.C.-A.D. 79), neither looking titillated; a few are explicit, like pieces showing men with super-size phalluses. Exhibition labels helpfully explain that these latter works were "thought to provide prosperity, good luck, and protection from evil spirits" and "were also symbols of fruitfulness."

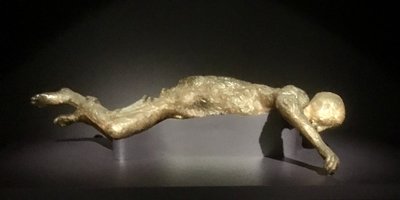

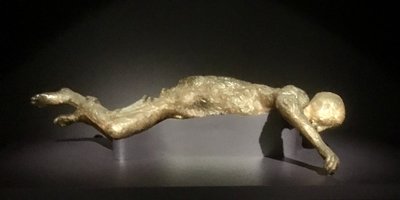

In the final gallery, a dramatically lighted vitrine contains the remains of a victim of Vesuvius. Found face down, now preserved in transparent epoxy resin, "The Lady of Oplontis" (a town about 2.5 miles from Pompeii) was carrying gold jewelry and a few coins when she ran for her life. She is a sobering end to an exhibition that expertly reveals the rich life of her compatriots, until death came down from the mountain.

The Lady of Oplontis |