Chicago

The first painting visitors to "Cezanne" at the Art Institute of Chicago encounter is "Undergrowth (Sous-Bois)" (c. 1894), a pine-forest scene painted from a bit below the trees, gazing up, with a barely perceivable horizon, and formed from patches of distinct marks that suggest just a slight fluttering. Some elements, like a rust-colored mound on the left, take shape only from several steps away.

Undergrowth |

More than a century after his death, Cezanne and his art remain puzzling, often paradoxical. He created stunning landscapes, still lifes and portraits that are central to the story of modern art, yet he worked mostly in Provence, far in distance and spirit from the Paris art hub. He could, as two sketchbooks here demonstrate, render exceptionally skilled drawings, yet many works, particularly those portraying bathers, suggest otherwise. He left many works unfinished, deliberately skewed planes, and created compositions that can only be described as crude. How he used paint—the feelings evoked from brushstrokes on the surface—was more important to him than his subject. Subsidized by his banker father, Cezanne painted for himself, not patrons or the art market, yet he widely influenced other artists.

Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen From the Bibémus Quarry |

In fact, some of Cezanne's best-known paintings might fall into that category—like "The Large Bathers" (c. 1894-1905), on loan from the National Gallery in London, an imagined pastoral scene of 11 faceless female nudes at leisure on a beach, angled to align with their surroundings. Although their thick bodies seem distorted and are tinged with an eerie bluish tone, some scholars suggest that Cezanne was extolling our oneness with nature and cite it as one of his greatest achievements. Throughout his career, Cezanne experimented with this motif again and again; this exhibition alone displays 18 drawings, watercolors and oils of bathers—some powerful, some gauche, all enigmatic.

Apples and Oranges |

When he wanted to, Cezanne could also paint luscious portraits. "Madame Cezanne in a Red Armchair" (c. 1877)—a refined work with light that shimmers across her striped skirt—is one.

It would hardly be a Cezanne retrospective without some of his multitudinous views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, the peak that presides over Aix-en-Provence, Cezanne's hometown. Among the 11 on display, the best is the vibrant "Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen From the Bibémus Quarry" (c.1897). It's a bright sunny day and yet, while the quarry's richly hued orange and ocher rocks and emerald-green pine trees occupy more than half the canvas, Cezanne directs viewers to his subtle, reassuring blue-gray-pink mountain in the distance.

As part of the exhibition, the Art Institute has followed a recent trend by examining some of the paintings here scientifically, shedding light on Cezanne's work methods—for example, how he mixed and layered pigments to enliven the appearance of his paintings and how he made slight changes in various compositions.

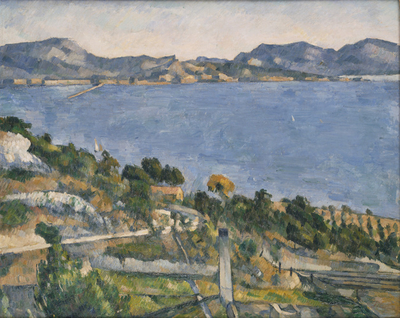

The Gulf of Marseille Seen from L'Estaque |

Exactly why artists, then and now, pay such homage to Cezanne relates to his devil-may-care attitude. His willingness to create art that is ugly, as well as art that is beautiful, and to defy other artistic conventions of the 19th century liberated them. Cezanne became known as an artist's artist. That same quality has made him a hard sell to much of the public. By acknowledging his mysteriousness, "Cezanne" may just bring more people around.