New Haven, Conn.

At the start of "Munch and Kirchner: Anxiety and Expression," at the Yale University Art Gallery, viewers are met with an 1895 lithographic impression of "The Scream," the renowned visualization of primal angst by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944). It leads to sections on death (including murder), women and love, anxiety, illness and urban alienation, and to excerpts from strange narrative works created while Munch and German artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) were confined (separately) to private sanitariums and being treated for mental illness. One, by Munch, parodies the Adam and Eve tale, while the other, by Kirchner, tells the story of a paranoiac who sells his shadow to the devil.

Munch, of course, famously suffered from mental maladies, addiction, the early loss of family members and more, and his career has been viewed through the mental-health lens before. But not together with Kirchner's. He, too, had a nervous breakdown and was an alcoholic, drug addict and depressive. Though they apparently met only once, they shared patrons, dealers and friends; both were innate Expressionists, basing their art on their inner emotions rather than depictions of the world around them.

Self-portrait With A Bottle of Wine |

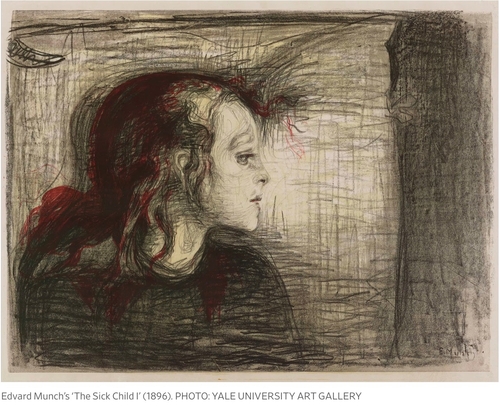

Yet the various approaches to content are more interesting, and none more so than those in the section labeled "Illness." Munch's many unforgettable images include "Death in the Sick Room" (1896), wherein his family stands by, silently, helplessly, as his sister Sophie fades away, their mask-like faces resembling the crowd's in "Anxiety." In "The Sick Child I" (1896), Munch offers a poignant view in a black-and-white lithograph of Sophie, with tinges of blood-red in her hair, lying in profile on her sickbed. It seems all the more painful when you realize that Munch made many versions of the image, this one nearly 20 years after her death.

Munch's torment is also evident in "Self-Portrait With a Bottle of Wine" (1930), where he's even more alone and more isolated, with only alcohol for a companion, than he was in a similar painting from 1906, which included other restaurant patrons in the background. Nearby hangs "Melancholy" (1930), probably a rendition of his younger sister Laura, who was institutionalized in public psychiatric facilities and whose slumping pose and solitude suggest hopelessness.

Kirchner's approach to illness seems more brutal. His "Head of a Sick Man as a Self-Portrait" (1918), with its sunken cheeks and hollow eyes, shows a deeply disturbed man and was made following Kirchner's excruciating service on the World War I battlefield. His unease at being among the mentally ill in a sanitarium and his strained relationship with food are on full view in a strong, skewed woodcut titled "Nervous People at Dinner" (1916). It shows three men in suits and ties at an abundant meal, with the table tilted upward to show the food they are not eating.

Kirchner's approach to illness seems more brutal. His "Head of a Sick Man as a Self-Portrait" (1918), with its sunken cheeks and hollow eyes, shows a deeply disturbed man and was made following Kirchner's excruciating service on the World War I battlefield. His unease at being among the mentally ill in a sanitarium and his strained relationship with food are on full view in a strong, skewed woodcut titled "Nervous People at Dinner" (1916). It shows three men in suits and ties at an abundant meal, with the table tilted upward to show the food they are not eating.

Kirchner tried, often unsuccessfully, to put distance between his biography and his art—and between his art and Munch's. In the wall text introducing "Illness," Ms. Spira cites Munch as embracing his troubles openly, calling his artistic output "rooted in the contemplation of disease." Kirchner, meanwhile, called Munch a "feeble hypochondriac." More ambitious and more competitive than the older artist, Kirchner craved recognition, which was never enough. He took his own life at age 58; Munch died from pneumonia at 80.

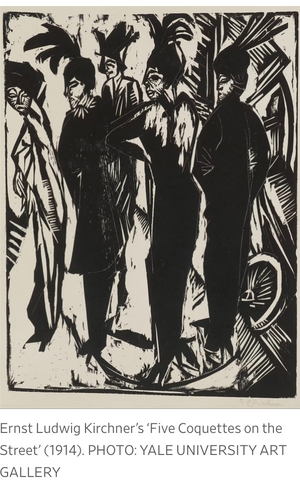

Kirchner's strongest showing lies in the "City" section. His sharp, angled images of urban life, especially those of domineering streetwalkers, align with his most valued paintings. With their feathered hats and arms akimbo, "Five Coquettes on the Street" (1914) look both jaded and tempting; "Women at Potsdamer Platz, Berlin" (1914) adds the local surroundings—shops, bustling businessmen and potential clients, the train station—but the women stand out nonetheless. Munch's urban scenes are softer, less frenetic, less raucous treatments of cabarets and showgirls.

Self-portraits, Kirchner and Munch |

The exhibition ends with a small display of landscapes by both artists. It serves as a coda, offering a little relief from the relentlessness of the show's anxious images. It suggests that both artists found some relief from their anxiety in nature, that art may have been therapeutic for them. It might be for visitors to the show, too.