San Francisco

Never shy—in art or life—Diego Rivera, Mexico's foremost muralist and arguably its best 20th-century artist, propounded a sweeping conception of "America," one that bonded Mexico with the U.S. and set them apart from Europe in culture, revolutionary spirit, societal aspirations, and innovation. In great detail, Rivera (1886-1957) proclaimed this conviction in "The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent"—the 74-foot-long, 22-foot-tall fresco that he painted, live before an audience, for San Francisco's 1940 Golden Gate International Exposition. Also known as "Pan American Unity," the mural depicts the past, present and future of his America through characters including Quetzalcoatl, Simón Bolívar, Samuel Morse and actress Paulette Goddard.

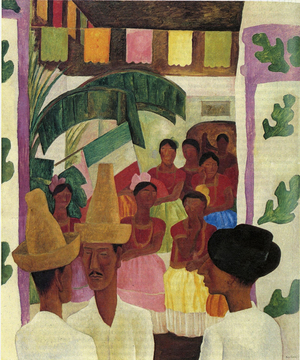

The Rivals |

The exhibition launches with a projection of "Creation" (1922-23), Rivera's first commission from Mexico's post-revolution government, which believed that art could help shape a new, inclusive national identity. It portrays Adam and Eve, the muses, and the classical virtues gathered under a heavenly symbol. But it flopped, deemed too metaphorical. Equally troubling (to Rivera, at least), it drew on Byzantine, Renaissance and other aesthetic traditions Rivera had learned while living in Europe (most of 1907-21), not the indigenous culture he aimed to elevate.

Lesson learned, Rivera devised the style that made him famous. Using simplified figures, with rounded shapes sometimes reduced almost to outlines, and often choosing earthy colors, he depicted the daily life, work, celebrations and rituals of indigenous and mestizo people. He endowed many figures, such as those in his sensitive "Mother and Child" (1926) and his moving "La Molendera (The Grinder)" (1926), with monumentality. In more complicated works—like "The Market" (1923-24), a fresco in Mexico City teeming with sellers, buyers and onlookers (seen here as a projection)—he called on his Cubist period in Paris, uniting slightly different vantages into a single image.

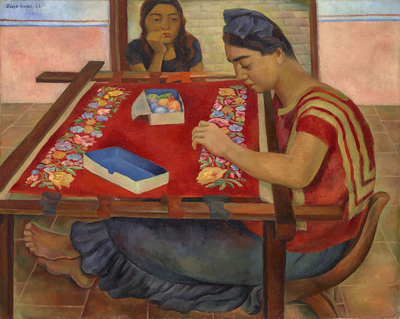

La Bordadora |

But to Mr. Oles's credit—and the exhibition's glory—many examples come from private or hard-to-see collections, works rarely (if ever) displayed publicly. "The Rivals" (1931), a colorful, nearly abstracted picture of men and women enjoying a traditional Mexican festival, was commissioned by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and stayed in the family until 2018, when it was purchased by Paul Allen, who died later that year; it is now in the family collection. The remarkable "La Bordadora (The Embroiderer)" (1928), which shows an indigenous woman sewing flowers into a bright red panel, had been locked away with a New Orleans family for more than 90 years until March, when it was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Except for its showing at auction, this is its first public appearance.

"Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees" (1931), a small fresco linking labor to the land and celebrating its fruits, normally hangs in a dorm at the University of California, Berkeley. "La Tortillera (The Tortilla Maker)" (1926), a strikingly simple but gorgeous painting valorizing the monotonous work of a woman, usually hangs in the dean's office of a medical school.

Girl in Blue and White |

Several other highlights merit mention. "The Flowered Canoe" (1931), led by a boatman whose face resembles Aztec sculptures, is filled with urban workers, well-dressed tourists, and an indigenous couple—capturing Rivera's ideal of a unified population. "La Ofrenda (The Offering)" (1931) commemorates the Day of the Dead practice in which children place food before an altar devoted to their ancestors. Rivera sets two girls amid abundant, verdant foliage whose leaves encircle them, framing their respectful act.

The Offering |

Sized to match Rivera's towering ambition, "Diego Rivera's America" convincingly shows the united America he wanted but one that never fully materialized the way he imagined.