Shelburne, Vt.

When, in 1932, the Metropolitan Museum of Art made its first purchase of a painting by a contemporary artist, it selected a still life by Luigi Lucioni. The Whitney Museum of American Art also bought a painting by him that year, and in 1930 the Museum of Modern Art had included him in its first exhibition of work by young artists. By then, Lucioni (1900-1988) had won numerous awards and been deemed a rising star in the art world. A gifted draftsman, he had earned admission to Cooper Union at age 15, to the National Academy of Design at 19, and to the company of established artists like John Sloan and Childe Hassam a few years later.

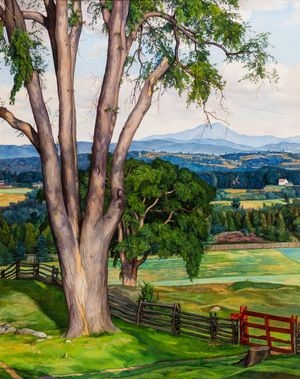

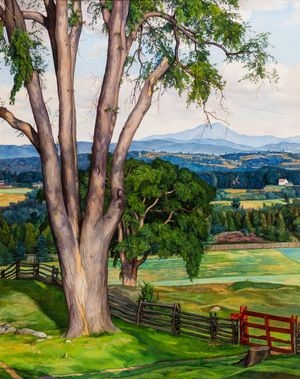

The Big Elm |

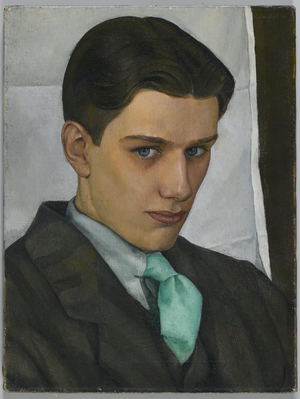

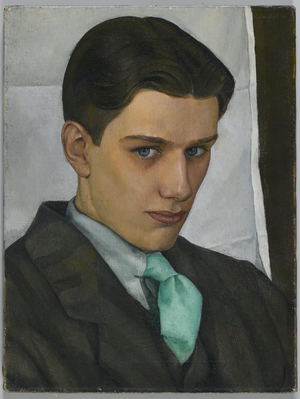

Today, Lucioni's name generally evokes a blank look, except for those in a small coterie of American art scholars and connoisseurs. Count among them Thomas A. Denenberg, the director of the Shelburne Museum, and Katie Wood Kirchhoff, curator of its very welcome exhibition, "Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light." With paintings like his fetching portrait "Paul Cadmus" (1928), his intensely realistic still life "Pears With Pewter" (1930) and his luminous landscape "The Big Elm" (1934), the exhibition is destined to be revelatory to visitors.

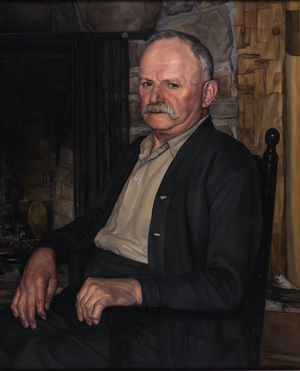

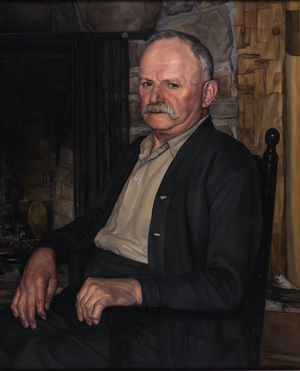

My Father |

Born in Malnate, Italy, in the foothills of the Alps, Lucioni had immigrated to the U.S. at age 10 with his family, settling in New Jersey. By 1917, he was spending a month every summer with relatives in Vermont. As a young artist, Lucioni also began traveling to Europe, touring museums and studying Italian masters like Giovanni Bellini and Botticelli. Struck by the similarity between his beloved childhood environs in Lombardy and the pristine Vermont terrain, Lucioni soon gravitated to Vermont to paint, spending summers there by 1931 and buying a home and studio in 1939 (while maintaining a residence in Greenwich Village, too). In the winter of 1931-32, he also met Electra Havemeyer Webb, a descendent of several wealthy families who married a Vanderbilt. She became his most avid patron—and the founder of the Shelburne Museum, which owns four of the 42 paintings and 10 etchings by Lucioni in the exhibition (plus others).

By then, Lucioni had developed his hallmark style: His works are highly detailed, but his meticulous brushstrokes are imperceptible. His palette is bold but natural. His images are harmonious, distinguished by an inner light, an uncanny clarity, a pervasive stillness and a transcendent timelessness.

Still Life With Peaches |

"Village of Stowe, Vermont" (1931), which opens the exhibition, serves as a perfect example. In the distance, the idyllic town occupies center stage, set against bluish mountains and surrounded by gently sloping greenswards. A lily-white church spire pierces the composition, just off-center. Subtly, the painting recalls the background of many Renaissance works.

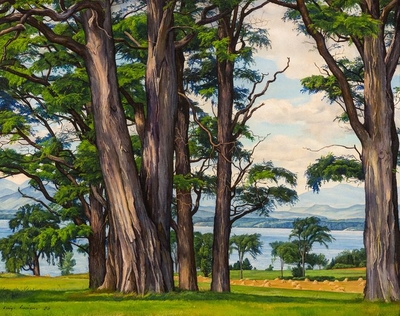

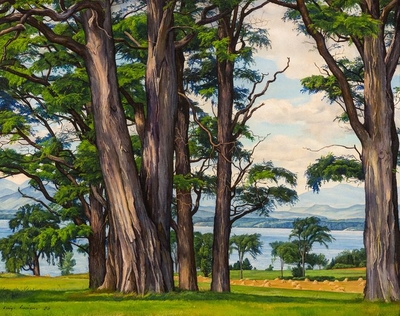

Lake Through the Locusts |

Lucioni, who painted

en plein air, achieved another stroke of brilliance in his landscapes that's evident in "Village of Stowe" and even more so in works like "The Big Elm" and "Lake Through the Locusts" (1936): an incredible depth of field that seems to extend the view forever. Credit his careful observation of distant details (sometimes aided by opera glasses) and his use of transparent glazes to sharpen the images.

Lucioni excelled at portraits, too, though he later claimed to dislike painting them. His are generally spare, serious depictions. A closeted gay man, Lucioni painted several pictures of men in his circle, such as Cadmus and "Jared French" (1930), that are coded with gay symbols like plucked eyebrows and sexually charged gazes. His other images, like "Portrait of Ethel Waters" (1939), are more straightforward. It shows the jazz singer and actress clothed glamorously in a red dress, her mink coat on the chair behind her, against a theatrically draped chartreuse curtain. With her arms tightly folded across her waist, her unsmiling face looks away, wary or perhaps weary.

Pears With Pewter |

Lucioni's most touching portrait depicts his father, a metalsmith. "My Father" (1941) places him in a wooden chair before a fireplace, his hands in his lap. Lucioni uses mostly muted colors—gradations of black, gray and brown—thus highlighting the flesh of his father's face, with its large jowls sagging into his thick neck, furrowed brow, unevenly aged eyes and shining temple. It's an honest, dignified portrayal.

Lucioni's still lifes showcase another genre he mastered. Some, like the gorgeous "Still Life With Peaches" (1927), with its sculptural use of a starched tablecloth and precarious positioning of a peach, pay homage to Cezanne; others, like "Bread and Fruit, No. 2" (1940), with windows reflected on a goblet, honor the Dutch masters. Always, though, Lucioni makes them modern with his choice of objects and distinctive style.

Paul Cadmus |

With so many exquisite paintings to his credit, why did Lucioni's reputation fade? The answer may be found in his final body of work—paintings like "Birches Over Pine" (1966) and "Farewell to the Birches" (1985). With their spectacular play of sunlight on the silvery white tree bark and the green lawns behind them, these paintings are seductive. But Lucioni made many—too many, apparently. Although they were happily purchased by wealthy tourists, art experts came to belittle them as formulaic and conservative.

Other artists have created repetitive images for tourists and they survived the criticism. "Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light" illustrates that he deserves the same. Its only fault is that it is not slated to travel.