Iowa City, Iowa

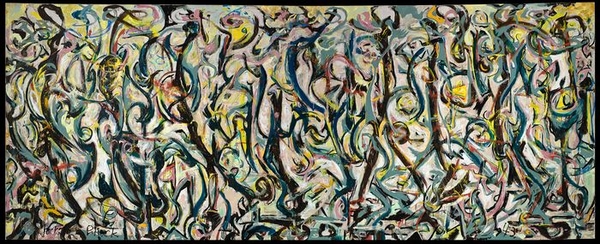

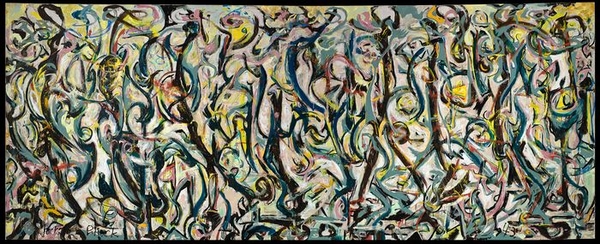

Chances are, many visitors to the Stanley Museum of Art at the University of Iowa have come especially to see its most famous painting—Jackson Pollock's "Mural" (1943). Commissioned by art patron and dealer Peggy Guggenheim, and later donated by her, the 8-by-20-foot painting, with its swirling black verticals and network of biomorphic yellow, gray, pink and red whirls, brims with energy. It was a breakthrough for Pollock, a bridge to his famous drip works, an arrow pointing to action painting and Abstract Expressionism.

"Mural" |

After being homeless and on tour to other museums since colossal flooding in 2008 rendered the old museum unfit for art, "Mural" recently returned to a brand-new building, with more than 16,500 square feet of indoor gallery space, where it anchors "Homecoming," the inaugural exhibition of some 600 works by 500 artists.

"E" |

Yet the first painting visitors see is not "Mural," which is beautifully showcased on the entire wall of a large corner gallery, but the crisp, brightly colored "E" (1915) by Marsden Hartley. This meditation on Hartley's German lover, a soldier who died early in World War I, is part of a renowned series that synthesizes Cubism, collage, trompe l'oeil and German Expressionism. "E" hints at what is to come, namely that the Stanley's collection of 20th- and 21st-century art comprises many more treasures than "Mural."

"Corn Country" by Lee Allen |

The exhibit name-checks many great artists with stellar works, including the vivid "A Drop of Dew Falling From the Wing of a Bird Awakens Rosalie Asleep in the Shade of a Cobweb" (1939) by Joan Miró; "Carnival" (1943), a triptych alluding to life, death, paradise and war by Max Beckmann; "Still Life With Fruit" (1920-22), an exemplary Cubist work by Georges Braque; and "Red No. 28" (1960) by Yayoi Kusama. It surprises with lesser-known but sterling works, such as Alma Thomas's exuberant "Spring Embraces Yellow" (1973), an abstraction that conjures sunshine and daffodils, and Elaine de Kooning's "Conrad Fried" (1954), a thoroughly modern, loosely painted portrait of her brother.

Organized by a curatorial team led by Diana Tuite, the museum's modern paintings section also offers thoughtful juxtapositions. The strong black verticals of Matisse's "Blue Interior With Two Girls" (1947) are echoed in two nearby Gee's Bend quilts, "Bricklayer" (2005) by Nancy Pettway and "My Way" (2012) by Mary Ann Pettway. Farm country appears in such varied ways as Edvard Munch's expressive "Grain Field" (1917); Diego Rivera's "Peasants Under a Tree" (undated) resting with their produce; Lee Allen's workhorses plowing rolling hills in "Corn Country" (1937); and Danny Lyon's poignant photograph "Cotton Pickers, Ferguson Unit, Texas" (1967-68), which depicts a group of incarcerated black men, uniformly dressed in white, synchronously stooped over in harvesting.

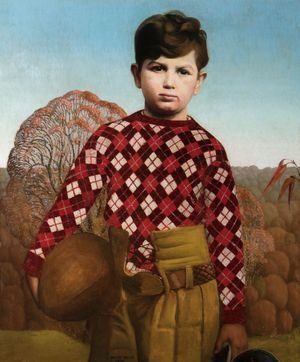

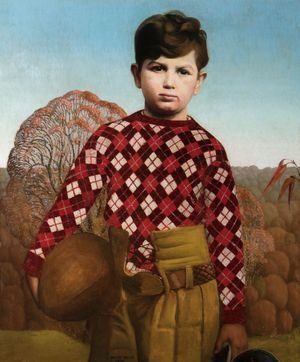

"Plaid Sweater" |

Another intriguing pairing contrasts Gordon Parks's "Untitled, Mobile, Alabama (Segregation Story)" (1956, printed 2022)—which shows a black girl and her grandmother eyeing a store window filled with neatly dressed white mannequins—with Grant Wood's "Plaid Sweater" (1931), a portrait of a confident, well-accoutered youth clutching a football.

There's much more—although not every artwork is first-rate—but the Stanley also boasts a bountiful collection of African textiles, masks, ceramics, carved wooden kings, mothers and reliquary figures, plus other objects. Dating from the first half of the 19th century to 2022, they occupy about half the museum's exhibition space, and come from countries including Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Ethiopia and Tanzania. Here and there, curator Cory Gundlach has inserted Western works to highlight cross-cultural affinities and the global nature of art. "Golden Enstrata" (1975-76) by the first generation Abstract Expressionist Richard Pousette-Dart, for example, deals with myths, as do African objects, while Andy Warhol's "Flowers" (1970) deploys colors similar to nearby textiles.

Man's Gown, Cameroon |

Many of these often canonical examples of African art stand out. In textiles, a colorful silk cloth (late 19th century) from Djerba island, Tunisia—vertical stripes of red, orange, green, white, black and more, many embroidered with geometric patterns—holds the place of honor; it's shown with a photograph of a Senegalese woman wearing a similar cloth as a shawl, situating it squarely in Africa despite the origins of the silk in France. Two large quilted tent panels of cotton appliqué on linen (1895-1898) in Khedival style come from Egypt and incorporate an abstract design, an arabesque medallion, and calligraphic Arabic text, accompanied by architectural features that suggest where they would have hung.

In masks, beyond such works as a simple copper oval face engraved with scarification marks (Ding/Kongo-Dinga style, before 1987), a beautifully carved, polished wood "Gèlèdé headdress" (Yorùbá style, late 19th century) includes a distinctive squared ear design that has allowed scholars to propose that it is a creation of the "Ànàgó Master" (Beninese, active late 19th century). He also created a similar headdress (20th century) nearby.

Mask from Cameroon or the DRC |

Some masks are far more elaborate, such as one in Tabwa style (c. 1940–1950), sewn with small, colorful glass beads, leather, rooster feathers and monkey pelt, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and one made of wood, human hair, glass beads, cowrie shells, pigment, and cloth, "Bamiléké-Dogon Ku'ngang Mask, Series: Visages de masques (VI)" (2019-22), by Cameroonian artist Hervé Youmbi. Visitors can watch a video of the mask used in a contemporary ritual.

With such variety and diversity on view, it's clear that "Mural" may be the reason visitors come, but the rest of the collection gives them many reasons to stay.