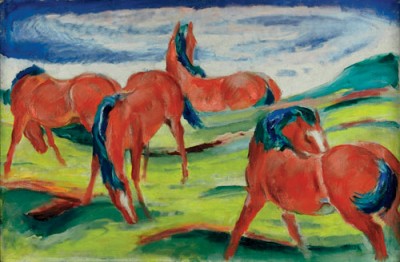

"Grazing Horses III," Courtesy Sotheby's |

In the past few years, German Expressionist paintings—especially those of the colorful Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) and Die Brücke (the Bridge) schools—have moved quickly to the top of the art world's "most wanted" lists. And the enthusiasm is spreading way beyond Marc, Kirchner, Feininger and other top-tier artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Max Beckmann. With their sales gathering strength and quality material in good supply, Expressionist works are looking to some market observers like the new Impressionists, long considered the ne plus ultra for collectors.

"The excitement was very, very evident in February," says Helena Newman, Sotheby's vice chairman of Impressionist and modern art and a specialist in German and Austrian Expressionism. The auction also included Impressionist and modern works, but "this was the hot area," she says. "We made the highest ever in this category, nearly $80 million."

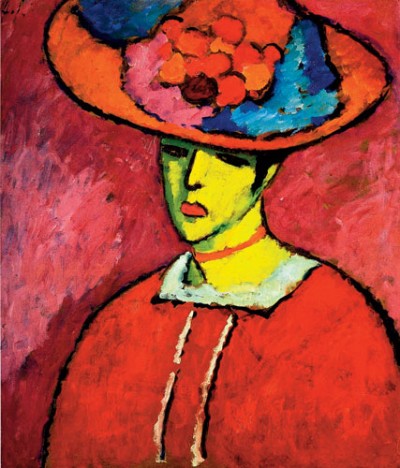

Jawlensky's "Schokko in Wide-Brimmed Hat," Courtesy Christie's |

Exactly why collectors have suddenly developed a fascination with these long-neglected artists is hard to pinpoint. For a start, says Jane Kallir, co-director of Galerie St. Étienne, in New York, "this has been an underappreciated category, one with a lot more good material available than in the French Impressionist and more heavily traded modernist areas."

But German Expressionism's appeal is not limited to its relative bargain status—it's also a sign of developing tastes and the broadening of collectors' interests beyond their national boundaries. Die Brücke artists, who came together around 1905 to create a powerful, emotional style emphasizing color and form and bridging the traditional to the contemporary, and the Blaue Reiter school, formed around 1911 by artists intent on giving their works a spiritual aspect, were popular in their own time. Their diverse, often distorted images—whether reflecting personal experiences or reacting to German politics—were appreciated as part of international modernism. It was the rise of nationalism, fed by the two world wars, that turned them into "German" Expressionists, encompassing both native artists and those working with them in Germany.

Some dealers believe that anti-German sentiment, especially after World War II, lowered demand for the works, as the French especially shunned them. Other dealers disagree, pointing to the fact that the Nazis labeled the Expressionists' art degenerate. Rather, they say, the style simply fell out of favor as American artists and Europeans like Yves Klein and Lucio Fontana came into fashion. "I spoke to a German dealer recently who said it was difficult in the 1970s to sell German Expressionists even in Germany," says Andreas Rumbler, Christie's German-art expert. "German Expressionists looked a bit dated."

Not anymore. Today their intense emotionalism seems incredibly modern, partly because collector preferences have moved beyond the formalist views of the 20th century, which valued abstraction, Minimalism and postmodernism, and partly because of the lack of any coherent "ism" in contemporary art. "This art has a humanistic content," says Kallir, alluding to its concern with common human conditions like dignity and rationality, "and we hunger for that."

One thing in favor of German Expressionist works is their bright Fauve-like colors. Another is their strong line, and a third is their wide-ranging subject matter. Some, like Emil Nolde's flowery paintings, are pretty and decorative and yet attain the highest artistic level. Others, like Kirchner's pictures, are stark commentaries. "A Kirchner street scene is a documentary of the time it was painted in," says Rumbler. "It stands for a period of German life."

The revival of interest in the German Expressionists has been fueled as well by the new popularity and high prices of their Austrian neighbors and predecessors, Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, and by recent museum exposure. In 2003 the Museum of Modern Art in New York drew wide acclaim for its huge retrospective of Max Beckmann, the first since 1964 to honor this emotionally charged and introspective painter. In 2001 the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis, staged "Franz Marc and the Blue Rider," also winning praise. Gordon VeneKlasen, a partner in Michael Werner Gallery, in New York and Berlin, also credits the opening in 2001 of the Neue Galerie, the New York showcase for German and Austrian art founded by Ronald Lauder. This spring Werner mounted the first New York exhibition of Kirchner's late works, drawn from the artist's estate, on view through June 14.

"Fifteen years ago, the taste for these pictures was almost exclusively in Germany," says Sotheby's Newman. Now, she says, collectors of all nationalities who are building strong holdings in 20th-century art believe they must include some works by German Expressionists.

At the same time, the supply of top-notch Impressionist paintings has dried up. That, say dealers and auction experts, means that the demand for Expressionist pictures is coming from collectors of 19th-century and of contemporary art. What's more, says Rumbler, "Expressionism attracts the widest range of ages, from young people to people in their 80s."

The good news for prospective buyers is that values haven't escalated as far and as fast as in other categories. "For the best of the German Expressionists, prices are where they should have been 15 years ago," Rumbler says. "But they haven't reached their peak yet. The best could still make 50 percent to 100 percent more in a few years time."

He and others expect good Kirchners, especially the artist's street scenes, to reach $50 million to $60 million, way above the record $38.1 million achieved in 2006. Great works by Marc, who died at age 36 in the Battle of Verdun, are scarce, with the majority owned by museums, and are thus destined to set further records. "A really good painting by Marc is an unparalleled event," says Newman. She calls the horse painting sold in February a "once-in-a-generation opportunity." A great Kandinsky would likely fetch $50 million or more.

Beckmann's paintings provide another example of the market escalation in German Expressionism. His oeuvre is less colorful, more fraught, and his biggest crossover appeal is to contemporary, not 19th-century, collectors. In 2001, Lauder bought the artist's Selbstbildnis mit Horn ("Self-portrait with Horn"), from 1938, for $22.6 million. Today it would likely go for $30 million or more, while a Beckmann triptych would likely bring $40 million, according to Robert Landau, of Landau Fine Art in Montreal.

Munter's "Yellow House with Apple Tree," Courtesy Sotheby's |

Landau also suggests keeping those auction prices in perspective. Take Jawlensky's Schokko, the painting that fetched more than £9 million ($18.6 million) in February. "I think it's a fair bet that the buyer was Russian, and the same for the Marc," he says. "When an auction house knows there's a market—they probably had one or two bidders—they put out a big guarantee and they draw out material. But does it mean the whole market doubled? I don't think so." Although Sotheby's won't comment on the identity of the buyers, those present at the February auction note that the winning bid for the Marc came via phone to Mikhail Kamensky, Sotheby's newly appointed Moscow head.

Russians' interest in Expressionism parallels their enthusiasm for Fauvism several generations ago. "They look at these works, and it's very much in their soul," says Rumbler. "It touches them—the expressionism combined with the incredible strength of color." He adds that the new Russian buyers are approaching collecting in the same manner as their forebears Sergey Schukin and Ivan Morosov, who at the beginning of the 20th century looked beyond Russia's borders for artistic treasures. Those collections, which were nationalized after the 1917 revolution, helped stock the country's great museums.

Coming off their strong February performance, neither Christie's nor Sotheby's had, as of press time, any potential record setters in their spring New York sales. But both Rumbler and Newman are hopeful about the summer auctions in London and the fall ones in New York. Getting consignments, says Rumbler, "is a result of long relationships with people who bought these pictures 30 to 50 years ago." When February, now the primary month for German Expressionist offerings, comes around again—well, that's when they're hoping to rewrite the records.