As soon as you walk into the New-York Historical Society, you start to wonder if someone has been smoking something. Strung above the arched entryway of this stuffy, 206-year-old institution is a garland of big red roses; nearby, there's a skeleton.

Yes, the Dead is back in town. The Grateful Dead: Now Playing at the New-York Historical Society runs through July 4 and puts the most comprehensive collection of posters, T-shirts, hand-decorated fan mail, backstage guest lists, awards, stage backdrops, and other Deadiana, alongside Lincoln and New York and New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth Century Portraits.

Yes, the Dead is back in town. The Grateful Dead: Now Playing at the New-York Historical Society runs through July 4 and puts the most comprehensive collection of posters, T-shirts, hand-decorated fan mail, backstage guest lists, awards, stage backdrops, and other Deadiana, alongside Lincoln and New York and New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth Century Portraits.

To answer the first obvious question—why is the ultimate Bay Area jam band considered a part of New York history?—the exhibit begins with a blown-up 1969 photograph of the Fillmore East, its marquee announcing a date for the Dead (as well as The Byrds, Jimi Hendrix, and Blood, Sweat and Tears). The famed East Village rock palace was "a home away from home" for Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, Bob Weir, and the other members, says Debra Schmidt Bach, one of the exhibit's curators.

The photo, and almost everything else in the exhibit, comes from a surprising source: The Dead were hoarders. They kept mountains of material sent to them by their fan base and tons of papers chronicling their 30-year history. (The Dead played together until 1995, when lead guitarist Jerry Garcia died of a heart attack. The surviving members continue to tour under the name The Other Ones.) In 2008, the group donated it all to the University of California at Santa Cruz. "It's hundreds of thousands of documents," says Christine Bunting, head of Special Collections and Archives at UCSC. Placed in folders and lined up end to end, the Grateful Dead Archive would stretch the length of two football fields.

What Bach and her co-curator, Nina Nazionale, have culled from the archive will spark more memories than one of Proust's madeleines. Photographer Herb Greene posed the band at the corner of Haight and Ashbury in 1966 and delivered the exhibit's most innocent picture; it sits near a multi-colored poster asking "Can You Pass the Acid Test?" Another photo shows Lesh and Weir at the Columbia student strike and campus shutdown in 1968; they were sneaked in on a bread-delivery truck.

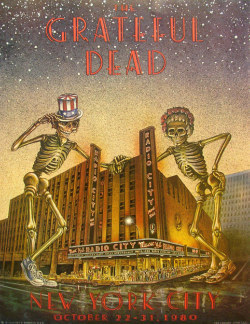

On one wall, 14 posters track the band from Radio City Music Hall (1980) to Madison Square Garden (a 1988 gig to benefit the rainforest with an image by Robert Rauschenberg) and beyond. Another wall features 16 T-shirts, including two by the late Staten Island designer Antonio Reonegro. One, a bright red shirt, depicts a skeleton scaling the Empire State Building, Madison Square Garden to his right, all superimposed on a map of Lower Manhattan.

The handiwork of Dick Latvala, a Deadhead who became the band's tape archivist in the 1990s, is also on display: He decorated their audiotape boxes with birds, flaming suns, and other images and notations. Sparked by Garcia's interest in the genre, comic books—authorized and bootleg (one says it's "unauthorized and proud of it")—began to appear and many of them are in the show.

Fans played a huge part in the Dead's story. To develop its fan base, the group placed a notice on the back of their second album asking "DEAD FREAKS" who wanted to be kept informed about their activities to send their names and addresses to the band's headquarters in San Rafael, California. Eileen Law, a friend, compiled and kept the list. She also started a newsletter called "Dead Heads" and managed the phone "hot line." If you ever called in, you might recognize the recordings, the scripts, and the ticket price lists, samples on view here.

To buy tickets by mail, the Dead asked fans to send requests along with a stamped, self-addressed envelope. And to increase their chances of getting what they wanted, fans began decorating their mailed-in envelopes. The archive contains 12,000 of them, and the pains ticket-buyers went through to get attention are amazing in the era of StubHub and texting.

To buy tickets by mail, the Dead asked fans to send requests along with a stamped, self-addressed envelope. And to increase their chances of getting what they wanted, fans began decorating their mailed-in envelopes. The archive contains 12,000 of them, and the pains ticket-buyers went through to get attention are amazing in the era of StubHub and texting.

Prospective business partners also sent items: a pack of skeleton playing cards, ties, prototype dolls of the group along with detailed production-cost estimates (rejected), a doormat and an umbrella with the group's dancing bear motif.

Jerry Garcia's custom-designed "Rosebud" guitar, borrowed from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, is also in the show, along with four clips from 1977's The Grateful Dead movie, directed by Garcia and Leon Gast.

There are unexpected items, too. Who knew that, in the boardroom of Grateful Dead Productions, the group sat in upholstered oak chairs of medieval-throne design, carved with "GD"? And plans for the famous "Wall of Sound," a public address system designed to get precision acoustics—are on display along with a film clip from San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom showing the final creation, which cost $350,000. "It lasted less than a year," Bach says, largely because it also cost $100,000 a month to maintain and weighed too much for many concert venues.

By the time visitors walk through the exhibit, the Historical Society hopes they have a better appreciation for the Dead's sophisticated music artistry, their business innovations, and their lasting legacy in American culture.

Meanwhile, back in Santa Cruz, most of the massive archive still hasn't been catalogued (though the federal government recently kicked in more than $600,000 to start digitizing it). Eventually, UCSC will make the materials available to scholars and the public in a special room to be called "Dead Central." But this is the only taste people will get for a while. Unlike the Grateful Dead, the exhibit isn't touring.