IT was late September, and Lowery Stokes Sims, a curator at the Museum of Arts and Design, was on the phone in her small white office, working out the shipping details for a piece in "The Global Africa Project," which opened on Nov. 17. Through her window, the giant silver globe in Columbus Circle glistened.

How apt. As she conceived the exhibition, Ms. Sims wanted to stress the "global" far more than the "Africa." Yes, she and her co-organizer, Leslie King-Hammond, director of the Center for Race and Culture at the Maryland Institute College of Art, chose artists who are African or of African descent, no matter where they were born. "Africa exists wherever these people are," Ms. Sims said.

But they also picked artists like Janet Goldner, an American sculptor of Eastern European descent who draws on her frequent travels to Africa, and the jewelry maker Ruth Omabegho, a native New Yorker who has lived in Lagos since the 1970s with her Nigerian husband, Billy, a sculptor whose works are also in the exhibition.

And they selected artists who've reached across the ocean for partners, like Algernon Miller. Based in Harlem, Mr. Miller strung about 110,000 paper beads, made by a women's cooperative in Uganda, into a wall tapestry. He's never met the 40 women who made the beads; his contact has been over the phone and the Internet.

Most of the exhibition — more than 250 works made by 107 artists and collectives — is devoted to jewelry, textiles, furniture, architecture, fashion, ceramics and basketry. But as Ms. Sims was organizing the show, she decided to include a sprinkling of photography, painting, sculpture and installation work too, in the belief that the line separating design and art is increasingly blurry.

The resulting visual farrago, a combination of traditional crafts, sophisticated urban design, fine art and much in between, is meant to make a point: African influence, itself infused with the cultures of colonial powers, has affected the world of art and design internationally, in ways both obvious and subtle.

Here's a look at five artists in the exhibition (click on this link for an interactive version, with additional pictures, on the NYTimes website).

Daniele Tamagni

From "Gentlemen of Bacongo" |

Daniele Tamagni was a freelance photographer, on assignment for the Italian magazine Africa, when in 2007 he discovered a group of Congolese men, members of the Society for the Advancement of People of Elegance, dressed to the nines in tailored, brightly hued suits. They mixed a hot pink suit with a red bowler hat, say, or a snow-white suit with a brilliant turquoise shirt. Given the contrast with the poverty around them, Mr. Tamagni said, "I was surprised to see these looks. I come from Milan, and I was interested in fashion, fascinated by their style." He decided to approach one of them, who introduced him to others in the group. They allowed Mr. Tamagni to take their pictures. In 2008 he returned to Congo, taking more photographs. He has published a book of the images, "Gentlemen of Bacongo," and has had exhibitions of the photographs. What Mr. Tamagni uncovered along the way was a subculture. "Some people think they are jokers, not serious people," he said. "But some appreciate the fact that they succeeded at this. They are popular because they are like actors. They are invited to parties because they give an elegant look to them. They are paid to go, like special guests, for weddings, funerals and birthday parties."

Duro Olowu

"Black Orpheus" dress |

Born in Lagos to a Nigerian father and Jamaican mother, Duro Olowu became a lawyer in London, where he lives, and is married to Thelma Golden, a New Yorker who is the director of the Studio Museum in Harlem. Deciding that fashion, not law, was his métier, Mr. Olowu introduced his first collection in 2005. Colorful, elegant and chic, it created a fashion flurry, and one dress in particular won him wide acclaim: the high-waisted, wide-sleeved Duro dress, confected from printed georgette and vintage printed silk jacquard for trim. "I reinvented freedom and joie de vivre in an African way, a wearable way," he said of the dress. Mr. Olowu's signature is his mix of patterns, colors and shapes — on display in a flowing "Black Orpheus" gown in the exhibition, which blends paisley, polka-dot and floral prints, cut on the bias and trimmed with ruffles. The resulting cacophony is very African, where such a profusion signifies wealth and prestige. "This is how women wear clothes in contemporary Africa," he said. "They may wear traditional clothes, but then they may mix it up with a Gucci scarf. You'll see chintz curtains mixed with African design. It's an offbeat strong aesthetic that influences my work."

Bibi Seck

Taboo stools |

The bright table and stools designed by Bibi Seck are made in Senegal, where recycling plastic is common. It's collected, cleaned with detergent, shredded and reprocessed into new multicolored products. Or, to get a pure blue or red product, say, the plastic must be separated before cleaning. Using that recycling tradition, Mr. Seck — who was born in Paris to a Senegalese family but spent 10 years of his youth in Dakar — created his "Taboo" furniture line. Intended primarily for users in Western Africa who traditionally sit on low stools around tables to eat, drink and talk, his pieces are made in Senegal by a local work force that can turn out 60 stools a day. Eventually the line will be sold in the United States and Europe. Mr. Seck's Taboo furniture, which comes in colors like turquoise blue, sea green and coral, has a playful sense. But Mr. Seck is a consumer designer to the core, always concerned with how the user will react to his work and use it. "The day the user is alone with our product they need to feel that someone took good care of them," he wrote in his artist's statement for the Global Africa Project catalog. "What makes it African is the source," said Mr. Seck, who regularly travels to Senegal but has a New York-based commercial design firm with his wife. Those products "are not African, even if I am the designer," he said. "I bring my certain sensibilities to it, but it's not based on where I grew up or who was my father. It's more everything I've gone through since I was born."

Ndidi Ekubia

Bowl by Ekubia |

The graceful, beaten silver bowls and vases of Ndidi Ekubia betray no obvious links to Africa. But Ms. Ekubia, born in Manchester, England, and now living in London, said she draws inspiration from her mother, who emigrated from Nigeria in the late 1960s, from "the stories she used to tell and what she said about the life she lived in Africa," from her African dress and from the "bits of wooden furniture" and other objects around her childhood home that came from Africa. African food, bright colors, fashion, language and what she called the "boldness of the African people" have all had their effect. "My work is quite emotional, and the character is quite strong," she said. "Africans in general are emotional people. They cry. They talk loud. African dress is quite loud." To make her pieces Ms. Ekubia hand shapes steel or wooden forms, making molds that often have a natural, organic feel. Then, she will set them aside for a while before returning to cover them in silver sheets. Using special hammers she beats the silver into place on the forms. "This is hard work," she said, again evoking "a connection to my African background," adding, "I watched my mother work so hard in this country." Each one can take weeks or months to complete.

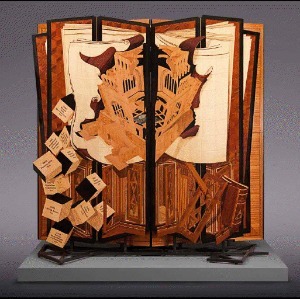

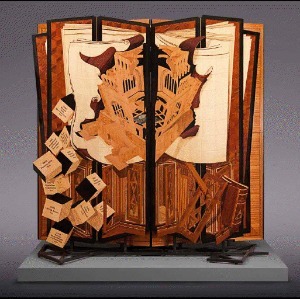

Kim Schmahmann

Apart-Hate |

Kim Schmahmann grew up in South Africa during apartheid, and his piece in the exhibition, "Apart-Hate: A People Divider," reflects on the horrors of that era. Seen from afar it's a striking marquetry room divider in warm wood tones — "eye candy," he called it. Up close it's an image of a world falling apart, a meditation on discrimination. The piece grew out of a gift, of sorts, from two South African women. Noting that Mr. Schmahmann had incorporated documents in an earlier work, they presented him with their pass books, the papers that black South Africans had to possess outside designated black areas. "It took me five years to work out how to do this without glorifying the pass book," he said. That was five years ago, and he's been working on the interconnected, three-section divider ever since. In the divider's first screen two wood panels depict the huge Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria, which honors the Boers who moved deep into South Africa, and the unraveling of the legal building blocks of apartheid. In the center screen newspaper accounts, images and other documentation of daily life under apartheid are displayed on a white grid. The third, a black grid incorporating a barbed wire frame, holds the pass books. "When people build walls that separate people, they cause suffering," said Mr. Schmahmann, who left South Africa for Cambridge, Mass., 20 years ago. "Those that are discriminated against suffer, but those that practice discrimination also lose out in a different way."