Over the past decade, as she set about creating the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Northwest Arkansas, Alice Walton has annoyed, alarmed and antagonized not only the art world but much of the rest of the populace too. Her offense? Ms. Walton, the youngest child of Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton, had the audacity to use her wealth to bring American art to a corner of the U.S. that had little. This upset both those who did not see why such a backwater deserved great art and those who would rather have Wal-Mart pay its workers better, a confusion of apples and oranges if ever there was one. Besides, skeptics said, it's impossible to build a comprehensive, world-class collection so quickly—despite the $1.2 billion lavished on this effort.

19th Century Galleries, Crystal Bridges |

Her vision makes for some odd moments. A room containing John Singer Sargent's masterly "Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife" (1885) and gleaming "Capri Girl on a Rooftop" (1878) offers none of the full-length society portraits the artist excelled at, but rather is dominated by two large-scale portraits of women by the far less talented Alfred Maurer. Later on, Andy Warhol is represented solely by his silkscreen portrait of Dolly Parton, a nod to locals but hardly an important work. And Wayne Thiebaud is seen not as a painter of luscious cakes or colorful landscapes, but by his mystifying, uncharacteristic "Supine Woman."

But there are great moments as well. One wall displays 16 of Martin Johnson Heade's iridescent "Gems of Brazil" (1863-64) hummingbird paintings, juxtaposed with five of his floral oil sketches. Asher B. Durand's "Kindred Spirits" (1849), the painting Ms. Walton purchased from the New York Public Library for $35 million, is flanked by the last finished painting by the artist Durand was memorializing—Thomas Cole's "The Good Shepherd" (1848)—and "Home by the Lake" (1852), by Cole's greatest follower, Frederic Edwin Church. In the Modernist galleries, five canvases by Stuart Davis line one amazing wall.

Fears that Crystal Bridges would sugar-coat American art may be true in the sense that it lacks the latest from profane or transgressive artists like Paul McCarthy, say, or Richard Prince. But the collection does not shrink from issues like race, shown in works by Kara Walker and Kerry James Marshall, or the American Indian experience, which is covered extensively, starting with the collection's earliest painting, James Wooldridge's "Indians of Virginia" (c.1675).

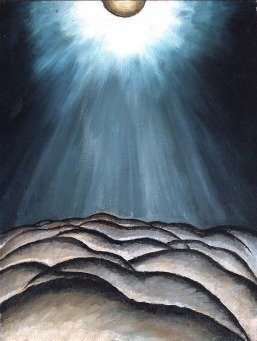

One of two works by Arthur Dove in the Modernist Galleries |

In the next gallery suite, walls painted deep red hold portraits and genre paintings: Works by Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer and Mary Cassatt stand out, but portraits by the lesser-known Dennis Miller Bunker and Gari Melchers hold their own. Another long, curved sweeping wall, this time painted blue, displays the course of landscape painting, starting with Thomas Moran's "Green River, Wyoming" (1878) and ending with two early 20th-century works, a teaser for what comes next.

That is where problems with Mr. Safdie's design, which begin with a clumsy entrance that requires visitors to descend to the lobby via an elevator, worsen. The galleries for early 20th-century art sit in a glass-walled bridge. Several paintings are strong—a 1908 portrait of actress Jessica Penn by Robert Henri, first-rate works by Marsden Hartley, and two beautiful abstractions by Arthur Dove, among them. But they are hung in enclosed, rectangular galleries that leave large empty spaces around them. Currently occupied by a few odd sculptures (including a giant wooden boy by Jim Dine), they are awkward areas not helped by the fact that sculpture is one of the collection's weak points.

In the next suite, for 20th-century art, both the white-box spaces and the collection take a downward turn. Ms. Walton has name-checked many of the great artists—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Joan Mitchell, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Bourgeois. But most are secondary works. There's a small early work by Pollock (not a drip painting) and a surrealist work by Rothko (not an emblematic Abstract Expressionist work). Meanwhile, the easily overlooked side galleries—tributaries off the main rivers of art history—need work. One, for artists' portraits and self-portraits, is a good idea with some excellent choices, especially Oscar Bluemner's wild-eyed 1933 self-portrait. But the theme is not sustained. The other side gallery, for figurative works made while abstractionism and later -isms reigned in the 1940s through the '80s, falls apart even more quickly. And this 20th-century art suite ends anticlimactically with a sour throwback to realism: Jack Levine's sardonic "The Arms Brokers" (1982-83).

For the moment, the temporary exhibition space (entered by a return to the lobby through the restaurant) also contains works from the permanent collection—recent pieces, often lighthearted, organized around the theme of nature. Eventually, these works will be integrated into the permanent-collection galleries, which will make for a better finale.

Critics will go through Crystal Bridges looking for gaps, and there are many: J.A.M. Whistler and Edward Hopper are among those represented by token works, for example. There's no late Winslow Homer, no Willem de Kooning, no combine by Rauschenberg. Ms. Walton passed on recent opportunities to purchase excellent Rothkos, Warhols and Clyfford Stills, to name just three.

But Crystal Bridges isn't finished; it's a work-in-progress with a $325 million endowment for acquisitions alone. And even now, it's worth the trip -- even if you have to change planes in Atlanta.