A few years ago, the Saint Louis Art Museum dug into its storerooms and saw a work that it had purchased in 1953 but not shown since, with some reason. "The Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley"—the only remaining of six known Mississippi River panorama paintings—was in terrible shape.

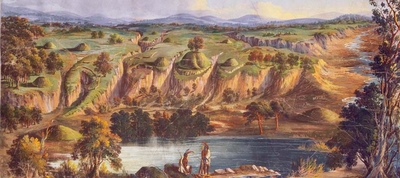

Scene 15: Chamberlain's Gigantic Mounds and Walls; Natchez above the Hill |

Dickeson's "moving panorama" wasn't meant to be shown in the round, like the famous 359-foot-long Gettysburg Cyclorama depicting the Civil War battle, or even all at once. Rather, as Dickeson performed, each scene in the panorama, strung between two vertical rollers, was cranked into place.

The constant unrolling and rerolling of the cotton muslin panorama, which was painted with a thin glue-based paint known as distemper, created cracks and wear in the paint and wrinkles and creases in the cotton. To varying degrees, all of the scenes—which range from the 16th-century burial of explorer Hernando de Soto to romanticized versions of Indian life to a cross-section of a mound Dickeson excavated, all rendered in vibrant colors and a melodramatic figurative style—needed repair before they could be appreciated.

Why not make it an exhibition? Several museums lately have taken visitors behind the scenes of the conservation process, and in 2009 the St. Louis museum itself turned a gallery into a painting conservation lab for the cleaning and restoration of three large 18th-century landscapes by Hubert Robert. People, it turns out, like to watch conservators do what they do.

Scene 2: Circleville Aboriginal Tumuli; Cado Chiefs in Full Costume; Youths at Their War Practice |

What they see is slow, painstaking work. Before the worn-away paint can be replaced, Mr. Haner lays each panel flat, face up, then sprays the entire surface with a mixture of 0.05% gelatin in water from a mister to relax the creases in the fabric. "The first time we did it was a little bit scary," he says. The moisture might have caused the colors to bleed into one another (it didn't). The fabric is also stretched just a little, to smooth it. When the fabric dries, the original paint is less powdery, more stable.

Then the conservators can get to work. They use water-soluble wax crayons to "inpaint," or fill in, the places where the original paint flaked away, carefully staying within the confines of the damaged parts. It's a process Mr. Haner chose after studying the nature of the wear and tear and the cotton material. "If we'd used paint, it would have bled a little into the fabric and caused damage to the original," he explains. In keeping with current conservation practice, the inpainting is reversible, should some better process come along.

What made the work—and the exhibition—possible is a 21st-century replacement for the panorama's 19th-century rollers, which had long since been lost. The museum found a local company to design and fabricate a motorized scrolling apparatus that rolls the fabric slowly and evenly. It also allows the panorama to stand upright, in a vertical position, while conservators work on most of each scene, and to be tilted backward into a flat, horizontal position when the team needs to reach the top 18 inches. When it's flat, an overhead camera captures the action for viewers, projecting it onto a nearby screen.

"Interaction with the public is the main thing," Mr. Haner says. Despite a scheduled daily Q&A period, the team is often interrupted by questions. He usually insists that "two or three people keep their nose to the painting, and one of us answers the questions"—otherwise they wouldn't get the work done. The questions, though, tend to be so similar (Samples: How was the panorama damaged? How do you become a conservator?) that the museum has posted a "Frequently Asked Questions" panel near the workspace.

Scene 20: Huge Mound and the Manner of Opening Them |

Such conjecturing was Dickesen's folly, and his quirky views run through the panorama. Scene 2, titled "Circleville Aboriginal Tumuli; Cado Chiefs in Full Costume; Youths at Their War Practice," is completely made up, says Janeen Turk, the senior curatorial assistant in charge of the exhibition—Caddo Indians lived in Texas, not along the banks of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers as shown. Scene 11, a view of the tornado of 1844, shows the unlikely juxtaposition of an African-American woman fleeing, a white family crouched down in horror, and an Indian hanging on to the grass for dear life. In the background are flying branches and Indian mounds. Dickeson loved drama, and ordered Egan to create it.

As a historical document, the panorama leaves much to be desired. As art, it may be Egan's best work, but that's not saying much.

Yet those verdicts are not the point. The panorama is a relic: It shows today's viewers what 19th-century archaeology entailed and what visual entertainment was like in the 1850s, long before the emergence of technologies that limn the world today. That's why, when the conservation is completed, the museum plans to install the panorama in its permanent collection galleries. A facade wall will hide the roller mechanism, and viewers will see each scene, one at a time, as if Dickesen were still creating his show. Every now and then, a new scene will be rotated into view.