Why might one pick up a copy of My Times in Black and White: Race and Power at the New York Times, the posthumously published memoir of Gerald M. Boyd? To some potential readers, the title tantalizingly suggests that Boyd, an African-American who rose to become managing editor of The New York Times under ill-fated executive editor Howell Raines, will detail just how hard it is to be black even at an elite, liberal institution like the Times. Others may see the book as an inspiring story of a child raised in poverty in St. Louis who reached the profession's pinnacle, or thereabouts. Others may want the inside story of how Raines and Boyd lost control of the Times newsroom in 2003 during the Jayson Blair plagiarism scandal and were forced to forfeit their jobs. Still others may hope for a fall-from-professional-grace, rise-to-personal-triumph tale.

In this brutally honest account, readers actually get none of those things. My Times in Black and White contains elements of each. But Boyd, who died of cancer in 2006, fully develops none of them. (In fairness, he probably died before completing his manuscript; his wife, Robin Stone, edited his two drafts into this book.)

In this brutally honest account, readers actually get none of those things. My Times in Black and White contains elements of each. But Boyd, who died of cancer in 2006, fully develops none of them. (In fairness, he probably died before completing his manuscript; his wife, Robin Stone, edited his two drafts into this book.)

Boyd does succeed at one thing some readers will be looking for: payback. He casts Jonathan Landman, his main rival for the managing editor job, as chief villain. Blasting him variously as a "moody," "immature," "brash," "opportunistic," duplicitous and bigoted "bully," Boyd tags Landman not only for his downfall but also for several other bad moments he experienced.

Former executive editor Joseph Lelyveld--who wanted his managing editor Bill Keller, not Raines, to succeed him--fares poorly too. Boyd respected but was wary of Lelyveld, who "always had an agenda," he writes. Boyd says that Lelyveld had promised him the managing editor job but then reneged, choosing Keller. "The name felt like a dagger thrust into my gut," Boyd writes.

In this accounting, the knife was soon wielded by Keller himself: Once Boyd is managing editor, Raines tells him that Keller had advised Times chairman and publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. during his management deliberations that "under no circumstances" should Boyd be managing editor. Ignoring Raines' obvious manipulation, Boyd simply believes him, never mentioning any attempt to get another source or test Keller or Sulzberger for oblique confirmation.

Boyd doesn't dwell on these incidents, though--and that is both a positive and a negative, for he dwells too little on many things. Often he asserts and moves on without elaborating, even leaving adjectives and anecdotes to fall flat for lack of details. Landman is never shown to be "immature," "brash" and so on. At Boyd's first journalism job, at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, he says he learned that "the most important news sources are not always the elected officials but the people close to them ... that might be a secretary, for example." But readers get a one-sentence "Mr. Smith" example instead of a real-world one.

Likewise, describing a key moment in his Washington career, Boyd recalls spending Augusts keeping watch near President Reagan's ranch above Santa Barbara. The first year, expecting a news hiatus, he is "humiliated," and the Times embarrassed, when the Washington Post publishes a series of exclusive reports it had lined up in advance. The next year, Boyd proudly writes, "we did the same thing," beating or matching the Post. But what stories, what scoops? We never learn a one.

To find the real Gerald Boyd in My Times in Black and White, readers have to look beyond what he actually writes. They will find a man in near-constant turmoil, frequently changing his mind about the most basic issues. He reports to the Post-Dispatch after graduating from the University of Missouri in 1973 raring "to win a Pulitzer Prize, to make a million dollars and to grace the cover of Time magazine"; less than a year later, he is questioning his decision to become a reporter at all. He's ecstatic when chosen for a Nieman fellowship at Harvard but notes two pages later that "the novelty of the Nieman wore off. ... I found myself spending many of my days sporadically auditing a few classes or curling up in front of the television."

Even when he first accepts a job with the Times, he succumbs to a counter-offer from the Post-Dispatch, and calls the Times' Washington bureau chief to inform him of his change of heart. By Monday he has reverted. And by the time he actually starts the job he is questioning his choice. Before long he has developed a love-hate relationship with the Times ("my insecurities were on overdrive ... I had become a true Timesman," he writes).

The pattern is repeated in his personal life: With painful honesty, he recalls how he entered half-heartedly into his first two marriages.

Some of this is normal, of course: Who hasn't second-guessed himself? But as Boyd recounts his life story, readers may feel they are on a storm-tossed ship: He regularly veers from one position to another in a matter of a few pages, or even a few paragraphs.

Boyd's determination to sketch so many bad things at the Times as the product of racism--and everything good he achieved as a result of his doggedness--also seems both misguided and strange. In 1988, just five years after he joined the Times' Washington bureau, he was called to New York by then executive editor Max Frankel. Frankel told him he could skip steps on the ladder to management. "I would go on a 'fast track,'" Boyd writes, "performing a series of editing jobs that would allow me to develop my management skills." And he did.

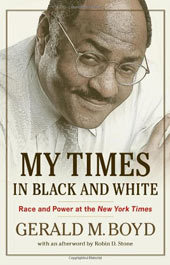

During my eight years at the Times--which ended right before he and Raines were asked to resign--Boyd elicited mixed feelings. Unquestionably, he strived to occupy the managing editor post and to balance Raines, who could be impatient, arrogant and brutally competitive. Boyd's obituary in the Times notes his irascibility and brusqueness, but that was a sometime affair. Boyd also had a softer side, often manifest in what former Times reporter Michel Marriott describes as "the Look ... [a] remarkable way of projecting profound skepticism yet genuine affection." It's captured on the cover of this book.

So perhaps it's natural that by the end of My Times in Black and White, the reader is left with mixed emotions, too. Sadly, because of his mercurial temperament and behavior coupled with his bitterness, Boyd's admirable achievements recede into the background. It's a pity that readers do not see more of the gentle, smiling, playful Boyd on the book's cover.