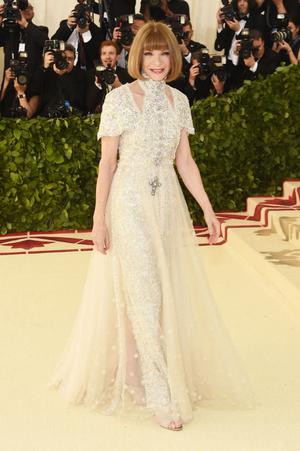

It's been called "the party of the year," "the Oscars of the East Coast," and "the Super Bowl of social fashion events." Held every year on the first Monday in May, the Metropolitan Museum of Art's annual Costume Institute Ball brings out celebrities, fashion designers, models and other glitterati to strut the red carpet at 1000 Fifth Ave. Organizer-in-chief Anna Wintour — Vogue's editor-in-chief — masterminds every detail, especially the guest list. To keep it utterly exclusive, she has trimmed attendance from as many as 800 to 550 or so, turning away scores who can more than afford the $30,000 tickets but who don't generate buzz or jibe with her definition of style.

With the likes of Beyoncé, George and Amal Clooney, Nicole Kidman, Derek Jeter and Bradley Cooper in attendance, the Met gala gets more ink and air time than any other charity ball in the country.

With the likes of Beyoncé, George and Amal Clooney, Nicole Kidman, Derek Jeter and Bradley Cooper in attendance, the Met gala gets more ink and air time than any other charity ball in the country.

Here's the catch: Almost all that glamor, attention, and prestige are underwritten by the American taxpayer. "Of course, we subsidize status," says Cornell University economist Robert H. Frank, who includes on his list of tax-advantaged status symbols sports stadiums and buildings at elite universities named for philanthropists and corporations.

With the Met gala, taxpayer subsidies occur in a number of ways. Tables for 10 command from $275,000 to $500,000, so as with all charity benefits, buyers may deduct that cost (minus the nominal cost of the meals, set at $250 per person). The Met doesn't announce the names, but they have a way of getting out. Over the years, Estée Lauder, Ralph Lauren and L'Oreal have hosted tables, and there are always up-and-comers, too: This year, Alexandre Birman — a Brazilian shoe designer celebrating his brand's 10-year anniversary — will be there, with supermodel Kate Upton among his guests.

For much bigger stakes, the Met gala also has underwriters, who often pay seven-figure sums to have their name in lights for the night as well as at the exhibition that follows. Count in this group the Gap, Moda Operandi and AERIN, a luxury brand founded by Aerin Lauder, granddaughter of Estée. Their spending is also tax deductible.

Although cast as philanthropy, these contributions give back to the givers, too, in incalculable, profit-enhancing ways. As a byproduct of their donations, those businesses gain favor with Wintour (left) — and with Conde Nast, where she is artistic director of its magazines. They receive publicity that enhances their brand, connects them to new, young consumers, associates them with a good cause, and may catapult their business into new spheres.

"The IRS clearly states that donors cannot get anything of value from their contributions, which is why they cannot deduct the meal portion of the ticket," said David Callahan, founder and editor of Inside Philanthropy and author of "The Givers." "Here we have a case where they get a full deduction and they're getting value that the IRS is essentially overlooking."

Over the years, Wintour has made that value bigger and more enticing to a wider range of businesses: The costume gala had been an affair for rich New York women and their husbands or escorts until she transformed it into a celebrity-dominated event. Still, as a search of the Met's press archive for the past 20 years shows, the sponsors were fashion, cosmetics or jewelry businesses like Prada, Tommy Hilfiger and Asprey -- until 2012. That's the year Amazon signed on as the main sponsor and when live streaming of the red carpet began, jacking up the value even more.

Since then, other tech titans have joined in — Yahoo in 2015 and Apple in 2016 and again in 2017. This year's exhibition, "Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination" (showcasing the influence of religious art on innovative fashions), apparently did not appeal to tech businesses. It is sponsored by Christine and Stephen A. Schwarzman (right) and Versace, plus, as always, Conde Nast.

But in 2015, Yahoo paid $3 million as co-sponsor of the ball and the exhibition, "China: Through the Looking Glass," which, with 815,992 visitors, ranks as the fifth-most-visited Met exhibition ever.

For that contribution, Yahoo claimed two tables of 10 at the gala, according to Women's Wear Daily. Yahoo's then-CEO Marissa Mayer attended, along with other Yahoo execs, and celebrities also sat at the Yahoo tables. At the time, Yahoo was trying to boost its Style section. Rubbing shoulders with the Costume Institute crowd came with intangible benefits that may have helped (indeed, page views did rise for that week, Yahoo told WWD).

"All tech brands have that desire to 'cross over' and be accepted by more traditional worlds such as fashion," says one high-powered public-relations executive, speaking on condition of anonymity out of business discretion.

When Apple sponsored the ball in 2016, CEO Tim Cook and Apple design chief Jony Ive attended and, according to Business Insider, other denizens of Silicon Valley did too. Google co-founder Sergey Brin, Tesla CEO Elon Musk, Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom, 23andme CEO Anne Wojcicki, and then CEO of Uber, Travis Kalanick, added to their personal cool quotients and raised the profile of their companies among the fashion- and celebrity-obsessed.

These status gains might be compared with those conferred by naming rights — the significant but hard to calculate value to having one's name on a building, be it Schwarzman at the New York Public Library, David Geffen at the New York Philharmonic or Wintour herself. In 2014, the Met added to her clout when it designated the galleries and other spaces occupied by its Costume Institute as the Anna Wintour Costume Center — a gesture of thanks for her fundraising, which at the time had brought in about $125 million and totals much more now. "It solidified her (and Vogue) as THE most important and influential person in fashion worldwide, period," the PR executive said.

These status gains might be compared with those conferred by naming rights — the significant but hard to calculate value to having one's name on a building, be it Schwarzman at the New York Public Library, David Geffen at the New York Philharmonic or Wintour herself. In 2014, the Met added to her clout when it designated the galleries and other spaces occupied by its Costume Institute as the Anna Wintour Costume Center — a gesture of thanks for her fundraising, which at the time had brought in about $125 million and totals much more now. "It solidified her (and Vogue) as THE most important and influential person in fashion worldwide, period," the PR executive said.

The attending celebrities who provide the event with bold-face name sizzle also gain publicity benefits and a certain value from their association with the Met and with designers. These are arguably are far from negligible. Most pay nothing to attend, and many adorn themselves with the designer outfits provided; they're beneficiaries of corporate largesse and other donors.

All of these gains in power and status go untallied. "The IRS may well recognize that donors get value from this, but trying to tax it would open up a Pandora's Box," Callahan said. Frank of Cornell agreed, saying he could not think of a way the IRS could assign a monetary value to these intangible benefits either.

What's more, though no other bash can compare in status benefits with the Met gala, much of the nonprofit sector depends on money raised at benefits. It's legal, it's traditional in the U.S., and changing the tax rules would weaken the hospitals, universities, museums and other causes that rely on them.

Callahan believes that there's a cost in public perception to the high-profile gala custom, however. "It feeds certain cynicism about some kinds of charitable giving," he said.

Frank, who has written extensively about wealth inequality, agrees — up to a point. "People will compete for status in one way or another," he said. "If they compete by making charitable donations, that's probably better than competing by building bigger mansions or buying bigger yachts."

Just as problematic are the intangible benefits reaped by the designers, who supply dresses and tuxedos to the attendees; the jewelers who lend diamonds, pearls and other baubles; the hair stylists and makeup and nail artists who coif and paint the attendees; and various other vendors. Wintour has a hand in these decisions too. She not only decrees the event's dress theme — this year, for "Heavenly Bodies," she ordered "Sunday Best" — but also matches celebrities with designers.

These suppliers — designers like Tom Ford and Zac Posen, who often escort their muse or favorite model — can deduct their costs as standard business expenses, reducing their taxable income dollar-for-dollar. It's hardly a small amount — these gowns can sell for tens of thousands of dollars.

In 2015, when Rihanna was hired to perform at the ball, she wore a long, golden yellow, fox-trimmed, hand-embroidered cape designed by Chinese designer Guo Pei, who started out 20 years ago and whose couture dresses "cost around £500,000," or $680,000, according to The Guardian. Later, Fashionista chirped: "while she hasn't had much name recognition stateside prior to this, she surely will now."

Tax expert Linda Sugin, a professor at Fordham University School of Law, agrees that the exposure conferred by the Met gala can be real. But she said that the U.S. system taxes the added value to their brands from the publicity and alignment with A+ list celebrities later on.

"We tax when the brand is monetized," she said. "They are business expenses and the way it comes back to us is when they make more profit when they sell goods." That's where you the designer-fashion consumer pay your share. A dress by this year's sponsor Versace, for example, has a higher markup — and thus more taxable profits — than a dress sold by, say, Zara.

"We tax that properly," she adds, though her calculation may leave out the intangibles. As Harold Koda, the former curator-in-chief of the Costume Institute, put it in "The First Monday in May," a 2016 documentary about the Met event, "high fashion, when it's paired with celebrity, becomes something bigger than both."

As Wintour cultivates sponsors and donors, that's a selling point.