In recent years, few museums have weathered rough times as publicly as the National Academy Museum on Manhattan's Upper East Side. Lackluster exhibitions, low attendance, annual operating deficits and a dearth of donors were suddenly compounded in 2008, when the NAM sold two Hudson River School paintings from its collection to help pay bills. In swift response, the Association of Art Museum Directors, a professional group of North America's largest museums whose ethics standards prohibit art sales for any reason other than buying more art, barred its nearly 200 members from lending art to the NAM. These sanctions forced the museum to cancel shows and made ambitious exhibitions impossible.

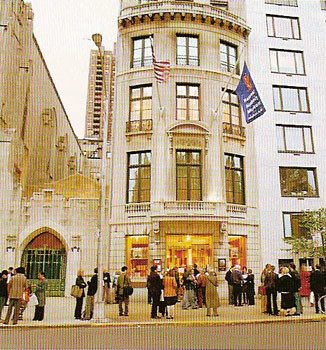

This month, Carmine Branagan, the National Academy's petite, self-assured director, hopes to put all that behind her. Over the past year, the National Academy has been renovated to give its Beaux Arts townhouse museum on Fifth Avenue a more welcoming lobby, upgrade its galleries and create more exhibition space in its adjacent National Academy School. The museum, which will reopen on Friday with six exhibits, is no longer a pariah, though it remains on probation until 2014 while it meets other stipulations, notably more fund raising.

This month, Carmine Branagan, the National Academy's petite, self-assured director, hopes to put all that behind her. Over the past year, the National Academy has been renovated to give its Beaux Arts townhouse museum on Fifth Avenue a more welcoming lobby, upgrade its galleries and create more exhibition space in its adjacent National Academy School. The museum, which will reopen on Friday with six exhibits, is no longer a pariah, though it remains on probation until 2014 while it meets other stipulations, notably more fund raising.

But even if all that goes well, Ms. Branagan faces a two-fold challenge: In a city loaded with museums, what niche exists for hers? And, in the 21st century, what artists want to belong to an academy? Going back to France in the 1860s, the word "academy" has connoted everything avant-garde artists have clamored to escape: It meant state control of their careers and it forced them to work in a realistic style and within approved genres, such as history and mythology, instead of developing new kinds of art. It's notable that while the National Academy can elect up to 450 members, it has only 320.

When the National Academy was founded in 1825, "it was the only game in town," Ms. Branagan says—there were no galleries, no museums, and few followers of American artists. But while it can never reclaim its 19th-century position as a dominant force, she says, "what the academy can do is reflect the living story of American art, and come to terms with who are the artists who are shaping that narrative."

To do that, however, academy membership has to reflect mainstream contemporary art. As recently as 2008, 70% of members were over the age of 70 and most made representational art—not exactly what is selling in Chelsea galleries. In the past three elections, the median age of new members was 58, among them Dana Schutz, 35, who paints disturbing narratives in bright hues. Other recent inductees include John Currin, who often paints titillating nudes; Janine Antoni, a sculptor whose work often relates to the body; and Shahzia Sikander, who makes Persian miniature paintings—all artists in their 40s. They've generally been "thrilled" to join, Ms. Branagan says, because the honor connects them with art history, and they've lowered the percentage of members older than 70 to 66%.

This year, members went further, though not without discord: They voted, 116 to 57, to allow as members visual artists of all types, as well as architects—not just painters, sculptors, graphic artists and architects, as previous rules dictated. But 147 did not vote. "A lot of the arguments against centered on painting as the core of the academy," Ms. Branagan said, "so if it's opened up to photographers, installation artists and others, that would diminish the legacy of the academy and create an academy that is unrecognizable."

The National Academy has modernized in other ways, too. To bring it back from the financial brink, Ms. Branagan—whose previous experience included posts at the National Audubon Society and the American Craft Council, but none at art museums—had to facilitate a change in governance. Before, academy members filled the board exclusively, but in 2010 they voted, 242 to 18, to add outside trustees who could bring not only money but also financial, managerial and marketing expertise to the table, just as other nonprofits do. Academy members retain a one-vote majority.

Yet far from sweeping away history, the renovated museum is stressing it. In the new lobby, visitors will learn about the National Academy's illustrious past on one wall, and looking up, they'll see a ceiling engraved with the names of all 1,995 members, from those elected in 1826, like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, to those selected in 2011, such as Christo and Kerry James Marshall. On the opposite wall, video and light-boxes will present rotating images of recent works. "You'll see something that has a 'wow,'" Ms. Branagan says.

Taken together, the opening exhibitions also convey a journey through time. "An American Collection" provides an overview up to 1970. "The Artist Revealed: A Panorama of Great Artist Portraits" displays a strength, because by tradition each member donates a work to the academy and many gave portraits—including Thomas Eakins, whose only fully realized self-portrait will be on view. An architecture exhibit highlights postwar drawings, models and photographs by the likes of I.M. Pei and Eero Saarinen, and recent works will be shown in a small installation focused on five members, including sculptor Elizabeth Catlett and photorealist Malcolm Morley, and a show of works made since 2000. Finally, there's a retrospective for Will Barnet, who was elected into the academy in 1982 and turned 100 in May.

They also capture the museum's unique niche, Ms. Branagan says: "We're committed to a living history of American art, and we're the only institution where the permanent collection is built through the lens of artists and architects."

Every year, the museum plans to mount rotating exhibits drawn from that permanent collection, which numbers 7,000 works. It will also continue its traditional "annual," which will now be "cross-generational," and will include a side-by-side juried selection of works by invited nonmembers. The NAM will also continue to showcase artists like George Inness and George Tooker, whose vision is underappreciated by the art market.

Will the public show up? The benchmark is low: Past attendance has averaged a meager 20,000 annually and Ms. Branagan is projecting a mere 20% increase over the next three years.

Likewise, the NAM has socked away in a reserve fund $11 million of the $13.5 million raised by its deaccessioning of the two 19th-century paintings. The $3.5 million renovation was paid for by bequests, but the academy has been running a $1 million to $2 million annual deficit for the past several years. Planning for an annual operating budget of about $6 million, it does not expect to break even for an additional three to five years—even with "heavy investment" in fund raising, marketing and communications.

Ms. Branagan has one more goal—which speaks to the National Academy's very essence. "We will only be successful if we create valuation around what it means to be an academician," she says. "We want people to say, 'who got inducted into the National Academy this year?' "