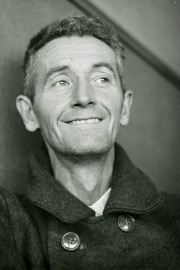

One May day in 1956, police in New Jersey stopped a skinny 43-year-old man wandering along the highway. Assuming that he was a vagrant, they thought his murmurings about being famous were mere hallucinations. But when they dialed the phone number he gave them, for his manager, they discovered that he was more than famous: Woody Guthrie was a legend.

Guthrie, who wrote "This Land Is Your Land" and more than 3,000 other folk songs, was suffering from Huntington's disease, a degenerative neurological disorder that at the time was completely misunderstood by the public. He was soon hospitalized at Greystone Park State Hospital in Morris Plains, N.J. And though his family, friends and acolytes, including a 19-year-old Bob Dylan, visited him there, a cone of silence descended on the five years he spent at Greystone and subsequent stays at other hospitals until his death at the age of 55.

Guthrie, who wrote "This Land Is Your Land" and more than 3,000 other folk songs, was suffering from Huntington's disease, a degenerative neurological disorder that at the time was completely misunderstood by the public. He was soon hospitalized at Greystone Park State Hospital in Morris Plains, N.J. And though his family, friends and acolytes, including a 19-year-old Bob Dylan, visited him there, a cone of silence descended on the five years he spent at Greystone and subsequent stays at other hospitals until his death at the age of 55.

"The story was always available, but not much research has been done on that period of his life," says his daughter, Nora Guthrie, president of the Woody Guthrie Foundation, created in 1972 to safeguard his archives and his legacy.

Enter Phillip Buehler, a photographer of "modern ruins," who one hot August day a dozen years ago snuck in via a window to the bowels of an abandoned part of Greystone (which exists today in modern facilities). He discovered decaying rooms scattered with files overflowing with patient photographs and records, and took some pictures.

Woody Guthrie |

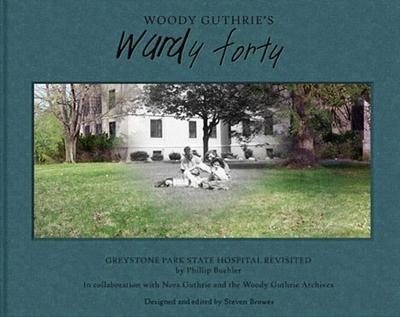

It was a call that led to the publication in November of "Woody Guthrie's Wardy Forty: Greystone Park State Hospital Revisited," a book of photographs set among historical documents about Woody. (The title references the nickname Guthrie gave to Ward 40, where he lived in the company of mentally disturbed patients.)

"When I saw his photographs, they reminded me of so much," Nora Guthrie says. Buehler's scenes of crumbling paint, cracked walls and rusty bedframes "are mirror images of the state my father was in at the hospital," she says. "So it was an opportunity for me to release the documents I'd been hanging on to for 60 years in an artistic way, taking the medical terminology out of the equation."

Buehler calls it "the story Woody left behind."

Nowadays, victims of Huntington's can live at home, says Nora, who is an honorary trustee of the Huntington's Disease Society of America, which her mother, Marjorie Guthrie, founded in 1968. But in the 1950s, no one paid much attention to the fact that Woody's mother also suffered from this hereditary disease, which causes shaking and other involuntary muscle movements, forgetfulness, impulsiveness and, sometimes, depression. He wasn't correctly diagnosed until after his arrival at Greystone, when a previous misdiagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia was discarded.

At Greystone, "there was no care," Nora says. "When my father picked up his food, he couldn't control his fingers, and he lost half of it — it stayed on his clothes for days. There was no one there to feed him. There wasn't a lot of dignity in those experiences."

She was happy to join with Buehler on the book about Greystone because, she says, "the more you don't tell, the more it's like a family secret." She views "Wardy Forty" as "an inspirational, hopeful, artistic project to tell people how my father dealt with 15 years in hospitals, especially as he was still writing, working and even feeding other patients. It must have been an experience living with 50 psychiatric patients, but he made peace with it."

"Woody Guthrie's Wardy Forty" juxtaposes 75 of Buehler's photographs of the abandoned wards with excerpts of previously undisclosed letters from Guthrie to his family; quotes from Guthrie friends and relatives whom Buehler interviewed; and unpublished photographs from the Woody Guthrie Archives, family and friends. The book also includes a photo of Dylan's unpublished, handwritten lyrics of "Song to Woody," which Buehler found during his research.

One poignant vintage shot shows Woody sitting between his two sons, Joady and Arlo, beneath "the Magiky tree." The Guthries chose that name for a huge, leafy tree outside Greystone to make their children's weekly visits seem like fun. As Nora recalls, her voice quaking a bit, walking through the psychiatric ward to see her father "was an absolutely terrifying experience for me as a child." So, instead, her mother entered Greystone alone to fetch her husband, leaving the kids (aged 6, 7 and 8 at the time) outside.

Greystone ward |

In another of the book's passages, placed opposite a photo of the tree, Arlo relates how the family would sometimes leave Greystone with Woody to visit the homes of friends, where they would play music and "goof off." Writes Arlo of his father, "(H)is work was booming as he entered Greystone. And I think my mom really wanted him to understand and participate in it to some extent, as much as he could. And that's what we did. That was our life."

Buehler also photographed a paper towel, on which Guthrie, in late 1956, tells his family in almost illegible handwriting to go on with their lives and leave him there — which they never did.

After his initial foray into Greystone, Buehler, who has been photographing America's "modern ruins" since 1973, revisited the grounds a dozen times, always surreptitiously, to capture its scenes in different light, from various angles and with eyes informed by his readings and interviews.

Over the years, the project grew from a simple picture book to a deeper collaboration with the Woody Guthrie Archives. Nora felt it was important to end the book, for example, with an essay on the history of Huntington's written by Alice Wexner, the author of "The Woman Who Walked into the Sea: Huntington's and the Making of a Genetic Disease" and a board member of the Hereditary Disease Foundation. There is still no cure for Huntington's, though drugs exist to reduce its severity and genetic research has made possible new therapeutic approaches. Yet Wexner's essay notes that people with the disease and their families are still stigmatized and "struggle mightily to find appropriate and affordable support and care."

For Buehler — who began photographing abandoned places when, as a high school student in the 1970s, he rowed out to then-abandoned Ellis Island — the book "has been a personal journey." He spent six years making it while working full-time at an advertising agency, and then another half-dozen "trying to get it out." He ultimately succeeded thanks to a crowd-funding campaign on Kickstarter that raised $43,924 from 438 people.

While clearly a terrible disease, Huntington's may have unexpectedly contributed to Guthrie's renown, says Brian Hosmer, an associate professor of Western American history at the University of Tulsa, not far from Guthrie's birthplace of Okemah, Okla. Noting that Guthrie's lyrics are frequently left-leaning, Hosmer — who organized a symposium commemorating the centennial of Guthrie's birth in 2012 — says that when Guthrie's music gained widespread popularity, in the '60s, it often lost its political context. Woody objected, Hosmer says, but "in an ironic way, his Huntington's, by silencing him, made it possible to bring him back as a different kind of figure, a more benign and less threatening figure."

Guthrie, now often called America's troubadour, died in 1967 in Creedmoor State Hospital in Queens, where he spent the last year of his life. "Wardy Forty is still there," Buehler says, adding that he has gone back only once in recent years, this time "with permission."