Los Angeles

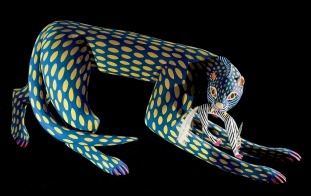

Three clay jaguars, modeled by hand, then fired and painted, stand—eyeing visitors—at the entrance to "Grandes Maestros: Great Masters of Iberoamerican Folk Art" at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Made in 2011 by Juana Gómez Ramírez, of Mexico, they convey the power, the pride and the beauty of Latin America's largest cat, which roams alone over wide swaths of terrain and is known as a fierce predator.

They also serve as an apt metaphor for this mesmerizing exhibition, which opens on Sunday [Nov. 9]. Encompassing about 1,200 works made of clay, metal, textiles, wood, glass, paper, leather, horn and even amber by some 600 artists from nearly 50 ethnic groups located in more than 260 towns in 22 countries, "Grandes Maestros" is bold, alive with tradition and imagination, and often as dazzling as those native cats.

They also serve as an apt metaphor for this mesmerizing exhibition, which opens on Sunday [Nov. 9]. Encompassing about 1,200 works made of clay, metal, textiles, wood, glass, paper, leather, horn and even amber by some 600 artists from nearly 50 ethnic groups located in more than 260 towns in 22 countries, "Grandes Maestros" is bold, alive with tradition and imagination, and often as dazzling as those native cats.

Every object belongs to Fomento Cultural Banamex, a nonprofit arm of the large Mexican bank owned by Citigroup. More striking, each one was selected by Cándida Fernández de Calderón, Fomento Cultural's director, as part of a social project. In 1995, in the midst of an economic crisis, she proposed a program to support the foremost Mexican folk artists, those who made "the most gorgeous expressions of folk art and were leaders of their communities," as she recently told me. The next year, she began to buy their work to exhibit and to publish. She helped them improve their workshops (providing better kilns, for example), train their apprentices and boost their marketing. In 2007, after proving the economic benefits in Mexico, she expanded the program throughout Latin America and to Spain and Portugal.

Ms. Fernández would arrive in each country, armed with knowledge of their specialties gleaned from tourist guides and, when available, books. She would spend two or three days talking with curators at local museums and buyers for traditional shops. Then she would set out in a taxi, sometimes traveling over bad roads for six or seven hours, visiting the best craftspeople she could find. She'd buy or commission works, paying on the spot and later sending another taxi to pick up the works for shipment to Mexico City. Often, the packing and shipping cost more than the items.

Not counting her travels in Mexico, Ms. Fernández says she made 35 trips in six years, which ended in 2013. She does not know how many miles she traveled. But Fomento Cultural now owns nearly 2,200 works of folk art. (A latter-day Noah, she often purchased two pieces (or more) from an artist so that Fomento Cultural could mount two exhibitions simultaneously; another version of this show is currently on view in Buenos Aires.)

I first got a glimpse of the collection when I visited Mexico City in July, 2012. In my last few hours there, on a Sunday morning when little else was open, I stumbled upon "Grandes Maestros" at Fomento Cultural's headquarters in the baroque Palacio de Iturbide, which was near my hotel. I was stunned by the feast of beautifully made and diverse objects—and their sheer number. After seeing "Grandes Maestros" in Los Angeles, I still am.

Indeed, with so many objects, filling 13,000 square feet here, the exhibition seems dauntingly vast. Yet the sum is truly greater than its parts: Ms. Fernández has created a sweeping cultural panorama. Visitors might begin by simply gazing at the installation and enjoying the wide view before letting their eyes land on specific items. (The museum has placed screens at each display area that, with one touch, will enlarge and identify each object in the exhibit, and trained staff will be on hand to relate the stories behind the works. It's also featuring one object from each country with special signage, an appeal to the many Hispanic communities that inhabit Los Angeles.)

As it was in Mexico City, the exhibition is arranged by material—groups of works in clay, metal, wood and so on. Aesthetically, this makes sense, at least partly because it illustrates the possibilities of each medium. Those expressive, naturalistic jaguars at the entrance are far different beasts than a hand-modeled, pug-nosed, umber-colored clay lion (2011) by Manoel Gomes Da Silva of Brazil, for example: the lion is "appliquéd" with stylized clay ringlets unlike any mane in nature. Not too far away, an all-black "fish pot" (2007) by Oscar Uriel Rodríguez Avilés, of Colombia, manages to be both sleekly modern and charmingly naive, with simple pectoral and dorsal fins for handles.

As it was in Mexico City, the exhibition is arranged by material—groups of works in clay, metal, wood and so on. Aesthetically, this makes sense, at least partly because it illustrates the possibilities of each medium. Those expressive, naturalistic jaguars at the entrance are far different beasts than a hand-modeled, pug-nosed, umber-colored clay lion (2011) by Manoel Gomes Da Silva of Brazil, for example: the lion is "appliquéd" with stylized clay ringlets unlike any mane in nature. Not too far away, an all-black "fish pot" (2007) by Oscar Uriel Rodríguez Avilés, of Colombia, manages to be both sleekly modern and charmingly naive, with simple pectoral and dorsal fins for handles.

Clay people are here, too, engaged in all kinds of activities. Cecilia Vargas crafts miniature buses, known as chivas, famed in her native Colombia for transporting individuals and their packages, animals and food, inside and on the roof. Her colorful, textured and overstuffed "Pitalito Express" (2007) bursts with everyday life. More sedately, Rosalvo Santana from Brazil has modeled a monochromatic, beautifully draped "Immaculate Conception" (2007) that looks as if it's carved from butter. Speaking of food, "Tree of the History of Mole" (1998), a canny unpainted clay sculpture by Alfonso Castillo Orta of Mexico, recounts the history of that delectable sauce.

On the other hand, there's also fine Majolica pottery, not just from Spain and Portugal but Mexico, too.

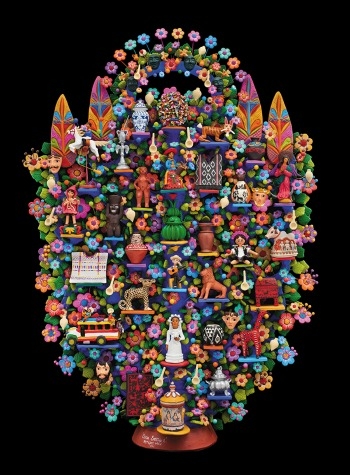

If I were forced to pick just one highlight, Mexican artist Óscar Soteno Elías's masterly "Artisan Tree of Ibéroamerica" (2012) [below] would be a strong contender. Commissioned by Ms. Fernández, this molded clay tree of life cleverly incorporates a folk art tradition from every country in the exhibition, some on view elsewhere in the galleries. The tiny bride centrally located in Soteno's piece, for example, replicates the primly dressed "Bride" (2008), her head wreathed in flowers, by Brazillian Isabel Mendes da Cunha, who started out making utilitarian pots.

As the most common medium for Latin American folk art, clay merits the largest section in "Grandes Maestros," but every material represented here seems to offer endless creative possibilities. Consider just three—no, four—examples in wood. Made in Mexico, Francisco Aguirre Tejeda's sophisticated "chest on cabinet" (2000) is constructed, carved and inlaid in a traditional design. A haughty, elongated "Creole couple" (2011) carved from red cedar by Cuban artist Juan Antonio Lobato Jiménez recalls the free-flowing musical and cultural atmosphere of Havana in the 1940 and '50s. There's a fabulous frog (2011) carved from ebony and polished to a high black gloss by Carlos Rosario Aranguren Rodríguez of Venezuela. And the curvy free-form flower vase (2011) made of petrified wood by Jorge Arturo Solano Solís of Costa Rica doubles as a modern sculpture.

Several sections offer easy opportunities for visitors to compare and contrast traditions. Masks, drawn from what Ms. Fernández says are the most important festivals in each country, fill one wall. (One standout: a multicolored, multi-horned fantasy animal made of molded papier-mâché by Miguel Caraballo García of Puerto Rico in 2011). Another area does the same for the most characteristic musical instrument of various countries—mostly strings.

In textiles, there's a cascade of serapes and tunics from several countries, another of short tunics, another of shawls. They are woven of wool, cotton, vicuña. Some are embroidered. A beautiful selection of white lace garments (blouses and christening gowns) and linens occupies central tables. This hand work is so perfect that it looks machine-made.

There is too much more to mention. But Fomento Cultural Banamex and Ms. Fernández have done something extraordinary by assembling a collection in an art category that has generally lacked exposure. An extravagant amount of imagination and an extraordinary number of hours went into these objects. They are visually rich not only because Latin American history blended ancient cultures with those of Spain and Portugal (themselves influenced by the Moors and other European countries), but also because these craft masters often took those traditions in new, contemporary directions.

There is too much more to mention. But Fomento Cultural Banamex and Ms. Fernández have done something extraordinary by assembling a collection in an art category that has generally lacked exposure. An extravagant amount of imagination and an extraordinary number of hours went into these objects. They are visually rich not only because Latin American history blended ancient cultures with those of Spain and Portugal (themselves influenced by the Moors and other European countries), but also because these craft masters often took those traditions in new, contemporary directions.

Many art museums still shun folk art—or limit it to small doses; Ms. Fernández will take this exhibit to other American cities, but likely to natural history, rather than art, museums. Yet "Grandes Maestros" proves that much folk art is worth celebrating, not because it's quaint or decorative, but because it's vital and genuine.