As every biker knows, there's a thrill that comes from speeding down a road, wind in your face. Victoria Findlay Wolfe, who rides a Harley, says she feels the same "strange rush" when she designs a quilt.

"Greatest Possible Trust" |

"She took something that was very traditional and made it modern, and that's not easy to do," says Melissa Wraalstad, the executive director of the Wisconsin Museum of Quilts & Fiber Arts, which gave Wolfe an exhibition in 2014. Wolfe, she adds, is on "the leading edge of that trend. She set it off."

And yet Wolfe—who grew up on a farm in Minnesota—became a quilter largely because of her grandmother, who made crazy quilts from polyester scraps. Like her grandmother, Wolfe doesn't use patterns and doesn't draw designs in advance. "All the design happens on the design wall, not on paper," she says—referring to a big wall in her studio covered with white cotton batting.

But hers are definitely not her--or your--grandmother's quilts. They are truly contemporary—bursting with unexpected colors like chartreuse, orange, and gray; brimming with allusions to New York City, lace, skulls, and heaven knows what else; loaded with surprising juxtapositions of striped, floral, starred, and other patterned textiles. Somehow they all work.

Wolfe with "Bright Lights, Big City" |

Wolfe's sewing skills go back to her childhood, when she crafted fashions for her Barbie doll. In college, where she earned a fine arts degree, she made her own clothes. She moved to New York to be a painter. But after she wed Michael Findlay, an art dealer, and became a mother, time for her art seemed to evaporate. So, using 15 minutes here and there, she started making clothes and then quilts for her toddler.

Today Wolfe doesn't just design and sell quilts. She takes commissions for them and teaches quilting. She has published two quilt books and has a third in the works. She designs fabrics, thread packets, acrylic shape templates, and die cuts (which allow the cutting of eight fabric layers at a time) for various manufacturers. She founded the New York City MOD Quilt Guild, serves on quilt group boards, and is an American ambassador for Juki sewing machines. She has organized quilt drives for homeless families and, sometimes, sends a quilt to a cancer patient, with no return address.

Wolfe is heralded because her quilts exude a finesse that other trendy quilts lack. "We've brought her in to teach and her classes are always sold out—people fly in from all over the country to take them," Wraalstad says.

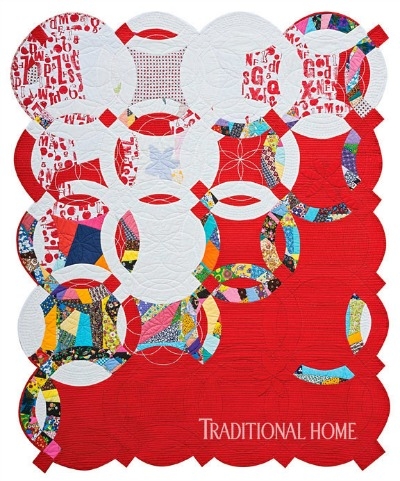

Wolfe is best known for her riffs on the traditional but difficult double wedding ring pattern. Her initial attempt failed. "I didn't like it and I chopped it up," she says. But she took the pieces and moved them around to create the award-winning "Double-Edged Love," a mélange of pink, black, red, yellow, and mostly white shapes and images. Those pieces stir up memories of her grandmother and life on the farm but also allude to New York City streets. "That was a game changer," Wolfe says.

Some of her products |

Wolfe--who names her quilts ("Greatest Possible Trust," "Bright Lights, Big City" and "Mr. Swirl E. Bones" are among the monikers)--demurs when asked about the meaning of "Double-Edged Love," calling it "too personal." But she says it speaks to the feeling that one can be both a country girl and a city girl, that one can love families and yet at times hate them. A bit of a workaholic, she applies herself 10 to 14 hours a day. She has become so busy that she frequently outsources to friends the actual quilting of her top-layer designs, which she always sews herself, so she can move on to the next design. "It's an addictive process, and I love playing at it," she explains.

Meg Cox, who writes and lectures about quilts, credits Wolfe's success to a fusion of her farm background, life story, and sense of play with "the heart of an artist."

"She pulls on something that is very authentic," Cox adds. "It fits the moment perfectly."