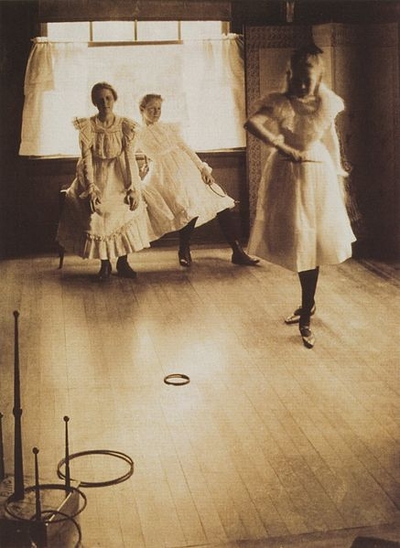

When Clarence H. White staged and shot "The Ring Toss" in 1899, he was on a mission. Eleven years earlier, George Eastman had introduced his Kodak camera for the masses, and many people were seduced by its slogan, "You Press the Button, We Do the Rest." They avidly captured everyday scenes, sent the camera off to Kodak for processing, and enjoyed the snapshots that came back.

Platinum Print |

White was soon celebrated in Ohio, and in 1898 he participated in the Philadelphia Photographic Salon, where he won broader acclaim. The next year, asked to jury the salon, he met other important photographers, including Alfred Stieglitz, Gertrude Käsebier and Edward Steichen, who were of similar mind, photographically speaking. By 1902, White had joined them in a group initially called "Photo-Secessionists" and later "Pictorialists." They crafted striking, often beautiful compositions and used manual techniques to develop and print photographs suffused with light, shadow and atmosphere—just like paintings.

"The Ring Toss" in the collection of the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y., is the epitome of their goals. To create it, White worked as hard as a painter or sculptor to make a dynamic, modern image that stood apart from most other photographs of the times. He arranged his three daughters in the "posing room" of his home, catching the eldest in action, ready to toss a ring, while her sisters watch from a bench behind her. Light, diffused by a white curtain, streams through the rear window (a common device for White); a window on the right side that has been cropped out adds to the highlighting glow of the eldest girl's left side. In the right background is a Japanese screen.

Detail showing that she moved |

White shot the photo using an 8-by-10-inch camera, and printed it on platinum paper, which produces images that are richer, warmer, subtler and more luminous than the gelatin silver prints common at the time. In the darkroom, he probably used glycerin to slow the process, allowing him to manipulate light and shade to create a moody effect, and he hand-processed the image to highlight some areas of the photo and shade others, according to curators at the Eastman Museum.

Taking his pictures, White used long exposures to achieve a soft look, and the girls would have had to maintain their pose for a couple of minutes. The one on the right moved, but White mitigated the double-image blur that resulted by retouching the negative, refocusing the viewer's attention on her face and the action.

At first glance, White's photograph is reminiscent of John Singer Sargent's "The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit " at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (which itself refers to Velázquez's "Las Meninas). Painted in 1882, it's an unusual arrangement of four girls at play, attired in white pinafores or frilly dresses amid two large Japanese vases. It, too, has an off-center composition—and much of the foreground is empty. The background is dark, save for a window admitting some light. Whether White saw the Sargent, either in person or in a reproduction, is thought possible but undocumented.

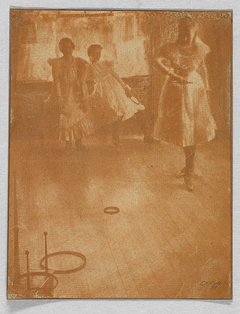

Gum Bichromate image |

White eventually quit his job as a bookkeeper, moved to New York to be close to other artists, and founded a school of photography whose students included Margaret Bourke-White, Karl Struss, Dorothea Lange and others who went on to fame. "The Ring Toss" remains one of his most celebrated images, existing in more than one print. The Library of Congress owns another in platinum; the Metropolitan Museum of Art owns a version made in gum bichromate, another labor-intensive process resulting in an image that some liken to red chalk drawings. The Princeton University Art Museum owns one of each.

Today the Eastman Museum, which occupies the renowned inventor's estate, owns millions of photographs, films, archives and ephemera that tell the history of photography. Even so, "The Ring Toss" is one of its treasures.