Santa Barbara, Calif.

Eik Kahng, chief curator at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, wants to change your mind about Vincent van Gogh. Many people who love his brilliant paintings (and who doesn't?) also believe they know him. Through biographies, movies and monographic museum exhibitions, they see him as a lone genius, a stormy social misfit, a suicidal depressive, a failure in his lifetime. And they surmise that his angst was the wellspring of his groundbreaking art.

"Wheatfield" |

This is not entirely new ground. Other exhibitions, notably "Becoming Van Gogh" at the Denver Art Museum in 2012-13, have explored the many influences that made Van Gogh such a towering talent. "Through Vincent's Eyes" differs in that it gathers far fewer Van Goghs (20 works vs. 70 in Denver, for example) but also displays some 75 works by about 60 artists he admired. The array goes beyond Van Gogh's well-known influences like Millet, Breton and Gauguin to encompass Chardin, Monet, Manet, Degas and many more, all present in one or more paintings.

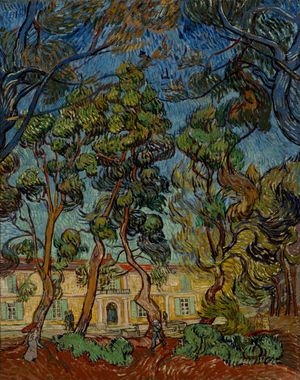

"The Hospital at Saint-Remy" |

Van Gogh was also an avid collector—largely of prints by artists he admired and, importantly, of prints from periodicals like The Graphic and The London Illustrated News. In an interactive computer display, based on research by Vincent Alessi, author of "Popular Art and the Avant-garde: Vincent van Gogh's Collection of Newspaper and Magazine Prints," visitors to the exhibition may page through a sampling of those collections. They'll see complex compositions of the urban poor, simple portraits of workers, and candid depictions of industrial landscapes, all neatly filed and regularly perused by Van Gogh. Tying any print to a later painting may be a risky enterprise, but—to cite one example—the resemblance between an 1879 print of a drayman and Van Gogh's 1888 "The Zouave" (in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and not on view here) is hard to ignore.

Raffaelli's "The Absinthe Drinkers" |

Van Gogh's paintings are always hard to borrow and the Santa Barbara Museum owns nothing by him, which made this exhibition—among the most ambitious in its history—no easy task. So while some works by him here are stellar, notably the luscious "Roses" (1890), "The Wheatfield" (1888) and "Hospital at Saint-Rémy" (1889), the exhibition thesis would have been strengthened by other choices: a figurative work, such as his 1889 portrait of a hospital worker, for example, or one of his many images of the sower (Millet's "The Sower," painted after 1850, is here).

Thus the exhibition sets out, as the catalog states, to "float" Van Gogh's works in "a veritable sea of art by other artists." As such, "The Outskirts of Paris" (1886) is intended to show that Van Gogh, like the social realist painter Jean-François Raffaëlli he much admired, avoided portraying the wealthy, urbane sections of central Paris favored by the Impressionists. Instead, using drab colors, Van Gogh focused on the areas to which the urban poor had fled following Baron Haussmann's modernization of the city. The underappreciated Raffaëlli is shown to great advantage with five paintings, particularly "The Absinthe Drinkers" (1881) and "The Return of the Ragpickers" (1879).

"The Outskirts of Paris" |

Yet to compare Van Gogh with Monticelli demonstrates how completely Van Gogh drew on what other artists were doing but melded it into his own luminous, expressive style, unlike any other's. "Through Vincent's Eyes" succeeds at showing Van Gogh as a far more complex and rational character than the conventional narrative dictates.