Oklahoma City

Oklahoma occupies a unique place in American history. It is home to more Native American nations than any other state, but that didn't happen naturally. In the 1800s, the federal government drove 67 tribes from their ancestral homelands into the area then known as the Oklahoma and Indian territories—from the Ottawa in the North and the Delaware in the East to the Seminole in the South and the Modoc in the West. By Oklahoma statehood in 1907, 39 remained—and 39 remain today. Only four (the Caddo, Plains Apache, Tonkawa and Wichita) originally lived on this land; four others came seasonally or to hunt.

Edward Red Eagle Jr. with his great grandfather's Osage coat |

One core exhibition, "Okla Homma," which means "red people" in Choctaw, begins at the very beginning. In a small theater, a 15-minute video loop illustrates the origin stories of the Pawnee, Euchee, Caddo and Otoe-Missouria tribes. These animated tales, projected on a surround screen, resemble other creation narratives. The Pawnees, for example, believe in a creator-god named "Tirawa," who pierced the darkness by making stars, then went on to create the sun, the earth and its creatures. Told with engaging stylized drawings, the videos come enchantingly alive.

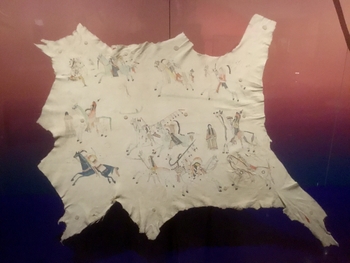

Kiowa Hide Calendar |

The 1830 Indian Removal Act, which forced the relocation of tribes located east of the Mississippi River, and the Dawes Act, which broke up reservations and coerced cultural assimilation into white society, are the painful nadirs. They are brought to life by heart-rending first-person video stories: One Apache man describes the dehumanizing fate of his grandfather, who was held by American forces as a prisoner of war for 27 years.

A lot is packed into these galleries, too much to be taken in at once. But there's a plus to the density. The varied kinds of display (videos, audio recordings, placards, artifacts, artworks, interactives) that repeat a tale or provide parallel stories offer multiple paths to learning about this history.

Moreover, here and there, the museum has inserted thoughtful grace notes. The origins-story theater fits into a space that, on the outside, resembles a curved black Caddo pot, decorated with a swirling rust-colored design symbolizing the sky, water and the earth, by Jeri Redcorn, a Caddo/Potawatomi. Inside, some seats look like boulders—natural resting places. Elsewhere, visitors can step into three "moving fire" circles—which honor the way glowing embers were transported during removal—to hear stories, as if they were gathered around a campfire.

Appliqued and beaded vests |

While they are emblems of cultural loss, many are beautiful. A hide calendar painted by a Kiowa named Silver Horn portrays men and their horses engaged in a historical event. A hooded baby's coat, trimmed in lynx and incorporating ears, eyes and a tail, illustrates Comanche dress. Moccasins, vests, drums, bags, baskets, vessels and more—examples are all here. And in one corner, behind cabinet doors, pictures of skulls on shelves, showing the "bone rooms" that housed human remains for study by anthropologists and doctors, often intended to help them assert white superiority.

Quapaw Moccasins |