Imagine a city where Jacques-Louis David insisted on working to execute a momentous commission from the French king; where a 21-year-old aspiring artist from Philadelphia named Benjamin West was taken to meet the pope; where Fragonard, Piranesi, Antonio Canova, Angelika Kauffmann and Jean-Antoine Houdon lived, dined, traded ideas and drank coffee together.

That was Rome in the 18th century. With these artists and many of other nationalities studying, working, competing and cross-pollinating, cosmopolitan Rome -- not Paris -- was the cultural capital of Europe.

Meng's "Adoration of the Shepherds" |

"Rome is where all the artistic sparks were going on," said Joseph J. Rishel, a senior curator of European paintings at the Philadelphia museum and one of the organizers. "It was like Paris in the 19th century and New York in the late 20th century."

"In this small town of 150,000 people," he continued, "there were a remarkable number of artists running around. Art and art news was a big deal."

In both art and architecture, quite a bit was accomplished. Between 1700 and 1800, the exhibition shows, artists in Rome perfected several late Baroque styles, made innovations in traditional religious imagery, resuscitated interest in classical antiquities, stimulated Neo-Classicism and helped lay the groundwork for Romanticism. True, some of the best-known artists of the period were French, like David and Houdon, but it is also true that they blossomed in Rome and produced many of their masterpieces there.

Benedetto Luti's "Education of Cupid" |

"It's a rediscovery," he said. "Our taste for the 18th century has been Chardin and Watteau. But you don't get to David by going through Chardin and Watteau; you get to David by going through Rome."

With 438 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, religious artifacts and decorative objects made by more than 160 artists, "Splendor" is the most complicated show the Philadelphia museum has organized to date. The works came from 186 museums, churches, institutions and private collectors in 16 countries. The curators called on 65 other scholars to contribute to the huge catalog, which they hope will become a classic.

In all, it took nine years to make "Splendor" a reality. But the exhibition's roots stretch back even further, to Anthony M. Clark, an art historian and museum director who died in 1976 at age 53 (while jogging in Rome). In the mid-1950's, Mr. Clark had begun researching and championing 18th-century Rome's role as a cultural mecca.

Three of the scholars who are now the exhibition's curators worked with Mr. Clark and were infected by his point of view: Mr. Rishel; Ann Percy, the drawings curator at the Philadelphia museum; and Edgar Peters Bowron, the European art curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (where "Splendor" will run from June 25 through Sept. 17).

Mr. Clark also knew the fourth organizing curator, Dean Walker, senior curator of European decorative arts and sculpture at the Philadelphia museum, and influenced many of the catalog contributors. In turn, they have imparted Mr. Clark's passion for the Eternal City to a second generation of scholars.

Promoting his revisionism was a big incentive for the exhibition's organizers, but hardly the only one. Rome in the 18th century was a visual delight. Civic and religious leaders commissioned the Spanish Steps and the Trevi Fountain. They built churches, piazzas, palaces, fountains, monuments, gardens and galleries. They embellished existing structures, including St. Peter's Basilica, whose interior was still incomplete at the time. Rich patrons, both secular and ecclesiastical, nurtured artists with commissions for paintings and sculptures.

Recreating that grandeur was part of the lure and the challenge for the curators.

Mr. Rishel recalls that the idea began to take shape in 1991, when he, Ms. Percy, Mr. Bowron and others met for a weekend in Umbria with Stefano Susinno, an art historian at the University of Rome III who was part of the exhibition team. "We filled his house in the country with books from the University of Rome," Mr. Rishel said. "We swam, we ate, we drank and we played party games, like each choosing the five most important works we wanted to make the point."

To chronicle an entire century, though, hundreds of objects would be needed. The curators began making lists of those they might want to borrow, then circulated them and consulted with other experts. They traveled in Italy and to many other places to observe firsthand the works that might be used to make their point. As usual, those trips included visits to places inaccessible to the public, like the 17th-century Quirinale palazzo of the Principessa Pallavicini, who agreed to lend a prayer bench.

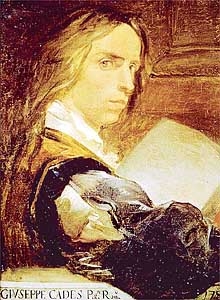

Giuseppe Cades's "Self-Portrait" |

The curators produced a master list and a databank of images on the Philadelphia museum's computer. Then they began winnowing.

In the end, Mr. Rishel said, the choices were guided by how well an object fit the themes chosen to give structure to the exhibition: the makings of modern Rome, Rome as the city of God, palatial Rome, the private lives of Romans and so on.

The curators said they had surprisingly little trouble arranging loans. The city of Rome and the Italian government had given their blessings in 1995, and, as the number of lenders illustrates, other institutions were enthusiastic about the exhibition's theme.

The result is a rich brew, even though the show lacks brand-name artists known to the public. "There aren't any from this time," said Mr. Walker. "Seventeenth-century Baroque artists and 19th-century artists of many schools simply outshine them in common knowledge. Being able to play star-maker, to shine a light on artists that they believe ought to be better-known, is part of the joy in curating this show.

"I don't think there are any artists of the caliber of a Bernini or a Caravaggio but there is a host of artists just beneath that," Mr. Christiansen of the Met said.

Curators ticked off a number of favorites. There is Giuseppe Cades. "He's our pet, a kind of imp who made a self-portrait that looks like Brad Pitt," Mr. Rishel said, adding that his altarpiece, "St. Peter Appearing to Saints Lucy and Agatha," was "one of the great sleepers of this exhibition."

There is Anton Raphael Mengs, a German who was celebrated as a new force in painting of his day, evident in his "Adoration of the Shepherds." At one point, Mengs goes to Spain to paint and meets Goya, who then goes to Rome, Mr. Rishel said. "Goya would not look like Goya without Mengs," Mr. Rishel said.

There is Pierre Legros II, "a transcendentally great artist who inherits the fallout of Bernini, refines it, turns it around and sends sculpture in a new direction that takes you to Houdon," Mr. Rishel said.

There is Benedetto Luti, who influenced Fragonard and Boucher and whose "St. Charles Borromeo Administering Extreme Unction to Victims of the Plague" is, Mr. Rishel said, "the most beautiful painting in the show." (His choice for that distinction, however, has been known to shift from time to time, his colleagues warned.)

"You have to mention Rusconi -- I love him," Mr. Walker insisted. Carlo Rusconi has four sculptures in the exhibition, including a marble bust of Pope Clement XI's aunt.

They cited Carlos Maratti ("a god," Mr. Rishel said), Batoni, of course (the "grand old man, who is all about beauty," he went on) and many more.

The public will ultimately decide which, if any, of the little-known artists in this vast exhibition become brand names. So far attendance has been good. And, Mr. Walker said, "they are staying for a long time. That's the best compliment."