St. Louis

Near the end of "Monet/Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape," three works by Monet, "Water Lilies" (1917-19) and two titled "The Japanese Bridge" (1918-24), display an unusual side of the great French Impressionist. Together, they show him using highly gestural, squiggly, intertwined brush strokes; intense, unnatural colors; mere hints of features like the bridge; exposed areas of canvas, and allover compositions that give the paintings a decidedly abstract quality. "Water Lilies" has sometimes been hung upside down.

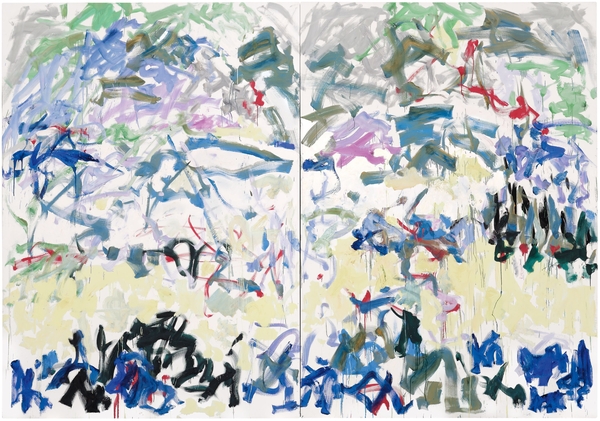

Willow branches |

"Tilleul" |

In 1959, Mitchell moved to Paris and, in 1968, to Vétheuil, a small town near Monet's famed home in Giverny, northwest of Paris. That is where "Monet/Mitchell" begins, zeroing in on Mitchell's final 25 years. (Although it had a similar title, the recent exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris was a broader, much larger show that included Mitchell's pastels and drawings as well as more paintings.)

"River" |

But, especially in Monet's late works (the earliest here dates to 1914), they overlapped more, and the commonalities are easy to see in these galleries. Each depicted flowers, trees, water, gardens, reflections and other landscape elements in expansive views on large-scale canvases, often joined in diptychs, triptychs and quadriptychs. Monet frequently painted images in series, varying the time of day, for example; Mitchell created "suites."

Water Lillies... |

Under the surface, Monet and Mitchell had deeper connections. In his late years, with his eyesight failing, Monet relied on his recollections to create paintings in the studio; Mitchell said that she painted "remembered landscapes that I carry with me," not specific places. The water in "Row Row" (1982)—a deep-blue diptych with patches of yellows and violets—could be the Lake Michigan of her early years or the Seine.

"Wisteria" |

Curator Simon Kelly doesn't attempt to match paintings. Rather, he charts the artists' responses to similar surroundings—trees, for example. Monet's lyrical "Water Lilies With Weeping Willow Branches" (1919) shows the tree's green leaves almost touching his cerulean pond. Mitchell's crisper "Tilleul" (1978) portrays a linden tree, its bare, black, wintry branches thrusting upward. Paralleling Monet's attachment to his willow, Mitchell depicted her cherished linden many times, including the more abstract "Red Tree" (1976). This suite, Mr. Kelly writes in the catalog, gave her solace.

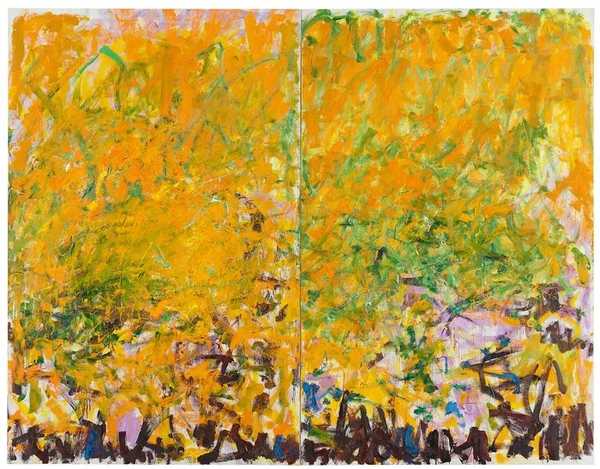

Mitchell could be lyrical, too. She loved the sunflowers in her garden, which she celebrated in an immense diptych titled "Two Sunflowers" (1980). A veritable blizzard of encrusted, intense yellow paint, fringed with black to suggest the soil, green for leaves, and violet for sunlight, it bursts with exuberance. Likewise, in the next gallery Monet's great "Water Lilies" (about 1915-26), the central panel of a renowned triptych split among three museums, speaks to the joy he took from his pond, which he painted more than 300 times.

"Two Sunflowers" |