MAASTRICHT, The Netherlands -- For two days last week, the scene at the Exhibition and Congress Center here, where the European Fine Art Fair was about to begin, could only be described as peculiar. Art was everywhere: thousands of paintings, sculptures, antiquities, antiques, icons, you name it. But no dealers were in sight.

The floor belonged exclusively to about 15 groups of men, and a few women, who moved from booth to booth in packs -- some with as many as a dozen members, some with as few as three -- inspecting every item.

The floor belonged exclusively to about 15 groups of men, and a few women, who moved from booth to booth in packs -- some with as many as a dozen members, some with as few as three -- inspecting every item.

Behind each group trailed a young Dutch woman or man jotting down their comments. Here and there a red tag was tucked into a frame or otherwise attached to an artwork.

These roaming inspectors made up the fair's vetting committee, the stern enforcers of standards of quality and authenticity, practitioners of a mysterious art whose deliberations are cloaked in secrecy.

Vetters can, and frequently do, order an item removed from a dealer's stand simply because it is "not in the best interests of the fair." They can command a dealer to change a description of a work, demoting a Rembrandt, say, to a "circle of Rembrandt," with an ensuing drop in price of millions of dollars. They can turn a 15th-century manuscript into a 17th-century copy.

Middle-aged dealers have been known to break down and cry about decisions, and lifelong friendships have been ruptured by differences of opinion. "There are real fights," said Peter C. Sutton, the director of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, who vetted paintings at Maastricht for several years.

But the potential buyers gain.

"When you fall in love with an object, your critical faculty goes to the four winds," said Dan Klein, an art history professor at the University of Sunderland in England who vets 20th-century decorative arts at Maastricht. The vetting committee is composed of curators, academics, conservators, dealers and the occasional expert collector chosen by the fair's executive committee to judge quality, condition and genuineness for fairgoers.

Price, however, is not considered; for that, buyers are on their own.

Most important art fairs, excepting those that show contemporary work exclusively, are vetted. But none is reputed to be as fastidious as this one.

"I know of no other fair that takes vetting this seriously," said Martin Zimet, a Manhattan Old Master dealer whose French & Company has shown here for three years.

So it comes as little surprise that "there's always a lot of drama at a place as strict as Maastricht," said Richard L. Feigen, another Manhattan Old Master dealer who exhibits here and who has vetted paintings at other fairs. "You're telling a dealer he's wrong." That is why the details of the process are supposed to remain secret. Members of the committee are asked not to discuss the subject. Dealers sign confidentiality agreements.

"You agree to abide by the vetting committee's decision, and its decision is final," said Adam Williams, a Manhattan dealer who had what he described as "a huge contretemps" with Maastricht's vetters a few years ago over a Dutch still life. He planned to make the multimillion-dollar painting the centerpiece of his booth but chose to remove it rather than change the attribution.

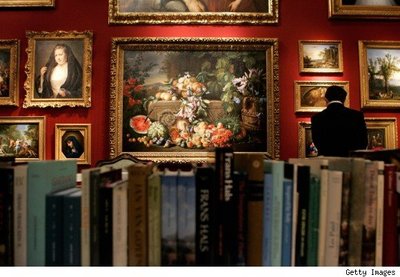

Scene from the TEFAF fair |

Soon after, as the drawings panel was assessing works at the nearby stand of De Jonckheere, of Paris, members saw a painting by Adriaen van Stalbempt (1580-1662) called "Landscape Illustrating Winter."

"Isn't that . . ?" cried an excited Carel van Tuyll van Seroosken, the drawings curator of the Tylers Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands, not having to finish his sentence. Another committee member, George Abrams, a lawyer in Boston with an extensive collection of Dutch drawings, ran back to the Haboldt stand to get the drawing. The match confirmed, the experts ripped up their earlier instruction and wrote, "This should read, 'Adriaen van Stalbempt, study for a painting illustrating winter.' "

'The Right Name Is Attached'

Mr. Haboldt, who bought the drawing at an auction in Paris a few months ago, said he had done as much research as he could before settling on Vranckx as the likeliest artist. Van Stalbempt, even drawings committee members agreed, is not known as a draftsman.

"I'm happy the right name is attached to it," Mr. Haboldt said, and probably happier still that the drawing sold almost immediately.

Still, he was not pleased that the story had been heard by a reporter, even with its happy ending. Dealers fear that the public's faith in them would be undermined if tales from the vetting process become known.

Opinion is divided, even among dealers, over whether the people who attend art fairs, including those who come to this small, inconveniently located 2,000-year-old town in the southernmost reaches of the Netherlands, know or care about vetting. Art lovers may simply benefit, oblivious to why everything looks so good here.

Vetting undoubtedly reinforces Maastricht's reputation as the world's greatest art bazaar. "The sales are greater at Maastricht because the buying public has the confidence that they're getting what they think they are," said Mr. Zimet.

Certainly, other dealers said, the process encouraged them to show their best works here, items that meet the standards outlined in the 12 pages of vetting guidelines given to exhibitors. Clocks, for example, must contain their original movements; furniture can be no more than 15 percent restored; restoration cannot be used to hide extensive damage to a painting. Besides filling out an information sheet for each work offered -- leaving room for the committee's comments -- dealers often bring supporting documents in case they are questioned.

Sometimes exhibitors can easily see how their peers have done. When the dealers are allowed to re-enter the hall on the second day of vetting, all red-tagged items are simply gone, plucked from their perches and placed in a truck that makes the rounds of all booths, leaving bare spots in its wake and delivering items to the reject room.

The vetters have no detailed instructions, said Mr. Klein, the British professor, except to be fair and to apply the highest standards. The tools of their trade are simple. "You bring a magnifying glass and your expertise, and that's about it," said Otto Naumann, a Manhattan dealer who vetted paintings for several years before exhibiting here.

The first cut is easy. "You throw the real woofers out right away," Mr. Sutton said. These include things that have been overpainted.

Then the real work begins. And it can be grueling. Like detectives, vetters are looking for inconsistencies in style, in color, in materials. Acute visual recall is required. Frederik J. Duparc, the director of the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, estimated that he and the other 11 members of the paintings committee examined 2,300 paintings by 1,500 artists in their two days of inspections.

Visual fatigue is the main occupational hazard.

Though they descend on a booth en masse, committee members tend to look at things individually or in small groups. Then, Mr. Sutton said, "if someone finds something he questions, we would gather round and discuss it." On 9 out of 10 items, there are no problems, Mr. Duparc said. But the 10th requires a discussion.

These deliberations can go on. Mr. Klein says his five-member committee has spent more than an hour talking about one object.

If no consensus emerges, there is a vote. On some panels, like that assessing 20th-century decorative arts, majority rules. On others, dealing with paintings, for example, three members can veto a description. That policy was instituted a few years ago, Mr. Duparc said, because the committee was large and some members felt more weight should be given to the opinions of a specialist on any given artist or school of work.

Vetters seem to love the job. "It's like a high-grade seminar," said Ivan Gaskell, a curator at the Fogg Museum at Harvard University who serves on the paintings committee. Mr. Klein said, "I learn more by these conversations than I sometimes learn in a whole year other ways, because we are all experts in something, talking frankly."

If there's a downside for the vetters, it's that they spend most of their time looking at the problem items, Mr. Duparc said. "You spend very little time at the best stands, and you'll walk by something gorgeous and say, 'Nice painting.' "

Committee members know that their trade is hardly an exact science. They come to Maastricht without knowing what they will see. But "it's like tasting wine," Mr. Naumann said. "You remember."

Not Exactly Foolproof

Some dealers, including Mr. Naumann (who said he could argue the question both ways), complain that only dealers see enough art day in day out to be the real arbiters. Yet dealers make up only a small fraction of the committees, because they can have conflicts of interest.

Mr. Klein said that criticism was valid. "To claim that vetting is 100 percent foolproof would be ridiculous," he said.

Dealers can appeal the vetters' decisions to the same experts, though many believe it is simply better to remove the items and take them back to their galleries. This year, dealers appealed only three decisions by the antiques vetting committee and about half a dozen by the paintings committee. The outcomes, as well as statistics for previous years, are confidential.

"Vetting still goes a long way toward guaranteeing an excellent fair," Mr. Klein said.

Even at Maastricht, however, caveat emptor is the best advice. Mr. Naumann tells the story of a dealer a few years ago who, at the instruction of the vetting committee, changed the label of a painting from "Jan Bruegel the Elder" to "attributed to Jan Bruegel the Elder." But "attributed to" was in little letters, Mr. Naumann said, and the dealer placed the card in such a way that the frame cast a shadow on those words. "It was," he said, "diabolical."