Last summer, much of the art world was aflutter about a 17th-century bronze by Adriaen de Vries (1550-1626) that suddenly appeared on the market. Cast in the year the renowned Dutch Mannerist died, it had never been recorded in the literature. Christie's found the 43-inch-tall Mythological Figure Supporting the Globe during an evaluation of an Austrian castle: the sculpture had stood atop a fountain there for at least 300 years.

Christie's put the piece in its July 7 evening sale in London, estimated at £5-8 million ($8- 12.8 million), suggesting that it might surpass the auction record for Old Master sculpture: £6.9 million ($11.5 million), paid in 2003 for an unattributed 15th-century bronze roundel from Mantua depicting Mars and other gods. But the estimate soon began to look conservative, as collectors of many nationalities and predilections, Russian oligarchs included, were showing interest. "I saw people looking who had never bought in this area," says longtime New York dealer Andrew Butterfield. Adds Eike S. Schmidt, the curator of decorative arts and sculpture at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: "It's difficult to say where it would have gone. I was hearing $30 million to $50 million."

Prometheus, by Giambologna |

Yet most Old Master sculptures, even with a solid attribution, sell for a small fraction of the price that a painting of comparable age, quality and provenance would command. A few years ago, the Tomasso Brothers, based in Leeds and London, discovered an unrecorded gilt-bronze Prometheus by Giambologna (1529-1608), the court sculptor to three Medici grand dukes. "The equivalent to that," says Dino Tomasso. "would be finding an unknown Bronzino portrait, which would cost £10 million." His firm is offering Prometheus for about £1 million ($1.6 million).

In 2009, the Birmingham Museum of Art took advantage of this painting-sculpture price gap. It had received about $1 million from a donor who wanted the funds spent on a triptych altarpiece, and approached the New York paintings dealer Richard Feigen about purchasing a picture. "For that amount, I told them, you'd get something insignificant," recalls Feigen, who steered the museum instead toward a marble relief by Mino da Fiesoli (1429-1484) that was in an exhibition in his gallery organized by the London sculpture dealer Sam Fogg. The elegant portrait of a young woman in profile is now the centerpiece of a gallery filled with Italian paintings.

Until the last few years, Old Master sculpture attracted a fairly predictable and limited coterie of buyers, mainly Old Master painting collectors like Jon Landau and Hester Diamond. Perhaps the chief force in this market has been Prince Hans-Adam II of Liechtenstein, who has been steadily amassing works for his museum in Vienna. In 2010, he paid the Duke of Devonshire £10 million ($15.2 million) in a private treaty sale brokered by Sotheby's for the bronze relief Ugolino Imprisoned with his Sons and Grandsons, by Leonardo's nephew Pierino da Vinci, from the Duke's famed Chatsworth estate.

But several high-profile museum exhibitions, among them "Set in Stone: The Face in Medieval Sculpture" at the Metropolitan Museum in 2006-07 and "Andrea Riccio: Renaissance Master of Bronze" at the Frick Collection in 2008-09, have reintroduced magnificent artists to the public and broadened their appeal. DeVries for example, though compared during his lifetime to Michelangelo, was all but forgotten until the 1998-2000 touring exhibition "Adriaen de Vries, Imperial Sculptor" traveled to the Rijksmuseum, the National Museum in Stockholm, and the Getty Museum. After the exposure afforded by these exhibits, "people realized that this stuff is beautiful," says Margaret H. Schwartz, director of the European works of art department at Sotheby's.

Pluto and Proserpina, by Steinl |

Like the rest of the art market, the Old Master sculpture trade has been affected by the global economic slowdown; however, demand remains strong at the top end. "What's more and more important is quality," says Schmidt. "For the great pieces, prices are very high." But great material is so scarce that dedicated auctions are few. Sotheby's holds dedicated auctions in London each July and December and reserves a section for sculpture in its Old Master paintings sessions in New York each January and, when there is sufficient material, in June. Christie's usually lumps sculpture into both London and New York sales for paintings and decorative arts. Both sell Old Master sculpture in house sales.

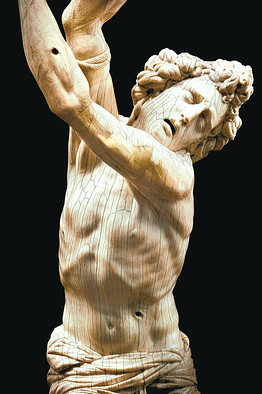

Dealers play a much larger role than in this market than in many other sectors. Although the auction houses have very knowledgeable experts, says Schmidt — who was one of them, having worked at Sotheby's—"the majority of connoisseurs in Old Master sculpture are dealers." Always searching for a forgotten or misattributed gem, which is where they make their biggest profits, dealers conduct or commission a substantial portion of the scholarly research necessitated by the paucity of monographs and catalogues raisonné. In early 2011, for example, when Butterfield came upon a massive 17th-century ivory of St. Sebastian in the hands of a South American dealer, he had it cleaned and traced it to Jacobus Agnesius, a little-known Germanic artist whose only universally agreed-upon works are in the Louvre and a museum in Albi, France. Butterfield engaged Schmidt to write a catalogue essay and then put the ivory up for sale with an asking price of $4.75 million. A private collector bought it not long after.

Butterfield, who stages exhibitions a few times a year in New York in conjunction with Fabrizio Moretti, who operates galleries in Florence, London and New York, is currently offering a terra-cotta Moses that was inspired by a Michelangelo drawing -- recently reattributed from Giovanni Francesco Rustici (1474-1754) to Francesco da Sangallo (1494-1576), a follower who worked for Michelangelo in the 1520s; he also has a carved wooden apostle lately assigned to the Spanish Baroque master Alonso Berruguete (1488-1561), whose only other work in the U.S. is in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Butterfield is asking $1.5 million and $1.4 million, respectively, for the figures.

The majority of Old Master sculpture dealers are based in Europe, close to most of the best material, although many have New York partners who host their exhibitions once or twice a year. Florian Eitle-Böhler, of the Starnburg, Germany-based Kunsthandlung Julius Böhler, for example, will partner with Blumka Gallery in New York in an exhibition timed to coincide with the auction houses' Old Master sales this month. Among the sculptures on offer will be Pluto and Proserpina by Matthias Steinl (1643/44-1727), a renowned imperial court sculptor in Vienna. Stolen during World War II from a branch of the Rothschild family and restituted not long ago, the piece is priced at $3.8 million.

Many sculpture dealers present at the annual TEFAF fair in Maastricht, to which they bring the choicest items. In a memorable transaction at last year's fair, Daniel Katz, of London, sold a pair of Baroque marbles depicting Jupiter and Juno by Giuseppe Piamontini (1664-1742) with an asking price of $2 million. The mythological couple had been recently rediscovered, although the compositions were known from smaller bronze versions in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Maastricht is known for its leisurely pace, but Stuart Lochhead, the director of Katz, says three people made bids for the duo in the fair's opening hours, and he closed the deal with collectors from California within a day.

St. Sebastian (detail) by Agnesius |

Beyond condition and provenance, what's desirable in sculpture varies with the material. "The process of making a sculpture is very complicated, and the techniques of making something in each medium differ," says Lochhead. "It takes more time to understand." For bronzes, which are usually produced two or three at a time, the quality of the cast and the patina are important. For marble, pay attention to the polish and the details. For terra-cotta, look for liveliness and fluidity in the composition. For wood, what matters is the quality of the carving and the details. The freshness of the composition is always critical.

Those are generalities, of course. Artists' intentions vary, as do collectors' tastes. Tomasso illustrates this point with French and Italian bronzes he is offering. The Rape of Proserpina, a bronze version of a marble sculpture at Versailles by François Girardon (1628-1715), to whom this piece is attributed, has a highly polished brown patina, with traces of red lacquer. A pair of bronzes by the Venetian sculptor Francesco Bertos (1693-1739), depicting scenes from Livy's account of the heroism of Marcus Curtius and from Pliny's tale of Dirce, has a comparatively dull finish, as the artist wished. The Girardon and the Bertos are both priced at nearly $1 million, but they will likely appeal to different collectors.

Even after all these factors are considered, putting a value on an Old Master sculpture is far from a science. Price, says Tomasso, is "very difficult to talk about. There are very few comparables." Despite the auctions at Sotheby's and Christie's, Old Master sculptures do not sell with great frequency. While this may present a challenge to dealers and specialists, for buyers it means they could well snag a treasure for a bargain price.