It took more than a dash of boldness for Timothy J. Standring, curator of painting and sculpture at the Denver Art Museum, to propose an exhibition about Vincent van Gogh. The museum doesn't own a single work by the artist, leaving Mr. Standring no anchor around which to build a show and nothing to offer museums that might someday want to stage their own shows of his paintings. Nor did Mr. Standring have many other trading cards; Denver's strengths are in American Indian, pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial art, which have no appeal for the European-paintings departments he had to approach for loans.

"For the first couple of years," he said recently, "I thought I might fail."

Yet on Oct. 21, six years after he first entertained the thought, "Becoming van Gogh" will open to the public, giving Denver its first-ever exhibition devoted to his works. Among the paintings and drawings on view will be at least 68 by the master himself and 20 by artists he studied. The number is unsure because, in recent days, one East European collector changed his mind about lending his van Gogh -- but, Mr. Standring says, "We're still negotiating. We have reserved a spot for it."

Standring In His Office |

He took an intellectual journey as well, for the exhibition's story line evolved as he and co-curator Louis van Tilborgh, senior paintings researcher at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, learned more, and as some owners declined to lend.

"I've never done anything more difficult in my life," said Mr. Standring, who's been organizing exhibitions for the Denver museum since 1989. Even the Van Gogh Museum, which gave its blessing to the project early on, referred to it once in his hearing as "the exhibition we thought would never happen."

The tale starts in 2006. Inspired by "A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599" by James Shapiro, Mr. Standring thought he could manage an exhibit of van Gogh's works from 1887 or 1888. "I thought that 30 oils and drawings would show the moment when he became van Gogh." In February 2008, he proposed the idea to Lewis Sharp, then the museum's director.

But 1888—when van Gogh painted many of his most famous works, including "Bedroom in Arles" and "Sunflowers"—wouldn't work. "The loans would be difficult to get and it would be too expensive," Mr. Standring said. And 1887 turned out to be the wrong year. Next he looked at two years, and the exhibit became "Van Gogh's Years in Paris, February 1886 to February 1888."

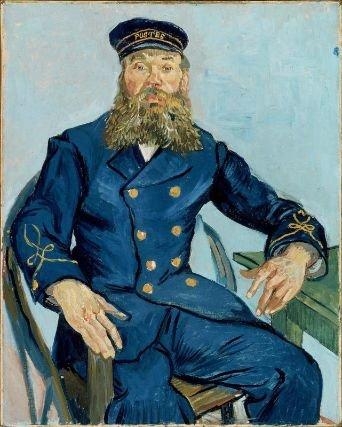

Postman Joseph Roulin, on loan from the MFA, Boston |

All along, Mr. Standring was keeping an "attack list" of works. "You had to double-check to see if they had been loaned and loaned too frequently," he says. "That narrows the checklist considerably." And there's competition—some museum is always organizing a van Gogh exhibition. Every request to a museum required a discussion, first, with the relevant curator. "You need the curator to shepherd it through the process," he says. "Of those curators, I knew a goodly number of them or I made contact through a friend. You ask around the network, 'how is the decision made' at x museum."

Some owners said no immediately. Finally, Mr. Standring says, "I was driving across Wyoming in the fall of 2009, taking my younger daughter to college in Bozeman, when I got a call from Jock Reynolds," the director of the Yale University Art Gallery. Cellphone service was spotty, but Mr. Reynolds was saying that Yale would lend "Square Saint-Pierre." That was the first loan.

Shortly thereafter, however, Christoph Heinrich succeeded Mr. Sharp as the director of the Denver museum. "He said, if you do this, do it big—make it the most important show—and that was the end of the search for 30 works in the exhibition," says Mr. Standring.

Soon it was the end of the Paris years, too. Now the curators were looking for works that would demonstrate how the mostly self-taught van Gogh struggled to master draftsmanship, understand materials and techniques, use color theory, learn from the works of other artists, and consciously devise his own trademark style. That required drawings and paintings from his early years in the Netherlands and his later years in Provence—and more travel, more letters.

To get the loans, "there is one big strategy," Mr. Standring says. "You increase the critical mass first, which encourages the others to lend. He continues: "You are supercurator, partially a psychologist, diplomat, negotiator, curator, art historian. You are constantly adjusting the various strategies."

He phoned some collectors until they agreed to lend or stopped taking his calls. He used humor, writing in an email to Matthew Gale, a curator at the Tate in London, that "I'd swim across the English Channel and risk my body for 'Houses With Thatched Roofs'—this exhibit is so important. He wrote back, 'I hope you are not wet because we approved the loan already.'" Mr. Standring used the same ploy with Aaron Betsky, director of the Cincinnati Art Museum—changing the locale to the Ohio River. According to Mr. Standring, "He paused, and said, 'OK, you've got it, but you have to do it in February in your Speedo.'" (Mr. Standring didn't, at least not yet.)

His cajoling didn't always work. "I went to Oslo three times, but never met the director or the curator."

Only a few museums asked for something in return. The Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen and the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University are each borrowing a different pastel by Edgar Degas, while the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid and the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh were lent a painting by Claude Monet.

One museum in Germany, which Mr. Standring declined to name, borrowed an Alfred Sisley in return for lending its van Gogh painting. But when Mr. Standring received the insurance value, "it was so high that I called and asked if the value included one zero too many. It was 85% more than the work was valued." The museum would not reconsider, and the loan was dropped.

"You have a lot of dark days when loans fall through," Mr. Standring says, who during this whole exercise has also been writing funding proposals, lining up catalog authors, writing his own catalog essays and planning the exhibition layout. How did he cope? "I painted in the evening—watercolors—because it's less expensive than a shrink," he says.