As Susan E. Bergh walked through the special exhibition galleries of the Cleveland Museum of Art one day last week, she was surrounded by wooden crates—some empty, some opened, some still locked. Inside were many of the objects with which she will reveal an ancient culture that is all but unknown to most Americans but is now recognized as the first great empire of the Andes.

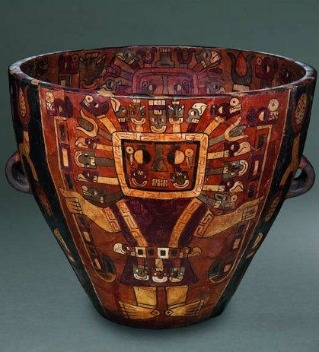

The Feasting Urn |

Judging by what is already visible, the show, which opens on Sunday, will do the trick. Ms. Bergh, Cleveland's curator of the arts of the ancient Americas, has assembled about 150 objects—intricate textiles, ceramic vessels, colorful featherwork hangings and four-cornered hats, inlaid ornaments, and stone and wood sculptures—from 45 museums and private collections in the Americas and Europe.

Even Ms. Bergh, who received a doctorate in art history and archaeology from Columbia University in 1999, started out focused on the Inca. But as a graduate student, she was advised against a project that required travel to Peru in an era of violence wreaked by the terrorist group Shining Path. Needing a museum-based project and "smitten" by Wari textiles at the Brooklyn Museum, where she had worked as a curator, she chose Andean tapestry tunics from the Middle Horizon, 500 to 1000, as her dissertation topic.

Wari Pendant |

That, says Ms. Bergh, who is tall and slender, with cropped graying hair, is partly because, like other pre-Columbian cultures, the Wari lacked a written language. While they were known to indigenous people and mentioned in one early Spanish account, the Wari "disappeared from the literature between the 1540s and the 20th century," when archaeologists began to excavate Wari sites.

The Wari also suffered from a mix-up. They shared iconography with the Tiwanaku people of Bolivia, who flourished around Lake Titicaca during the same period the Wari held sway to the north. In colonial accounts, the Tiwanaku figure as the Incas' ancestors, and museums took to labeling Middle Horizon artifacts as Tiwanaku. Only in the 1960s, after various discoveries and study, did scholars begin to clarify differences between the two cultures.

The Waris were an agricultural society that—as the first gallery makes clear—valued ritual feasting. "They used it as an expansion mechanism," Ms. Bergh says. They would invite other elites and, with conspicuous generosity, establish their prestige and create indebtedness. Indeed, in 2004-05, when the Wari did burst into the U.S. media, it was because a massive Wari brewery, which made corn beer called chichi, was discovered at Cerro Baúl. When the Wari abandoned the site, they drank the last of the brew and staged an elaborate rite that included torching the complex, which collapsed the building and inadvertently preserved it.

Ms. Bergh points to a prominent spot in the first gallery reserved for a large feasting urn borrowed from the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Anthropología e Historia del Peru in Lima that had not yet arrived. (Peruvian institutions shared about 35 objects, which are scheduled to be delivered on Friday.) It was reassembled from fragments, also part of a purposely shattered cache of ceramics discovered in the 1930s.

The catalog shows it as a spectacular piece, covered in a design of warm brown, rust, cream and olive tones and displaying, outside and inside, one of three principal Wari images, the "staff deity." This supreme religious figure, adorned with a halo of appendages, stands in a frontal pose, wears a tunic, and holds two staffs, likely signifying divine and earthly authority. Who this personage is, even its gender, is unclear, Ms. Bergh says, but it is featured in nearly all mediums.

The staff deity often appears with two other primary images. Staff-bearing winged carriers, rendered in profile and on bent knee, attend the staff deity. And there's the sacrificer, a figure shown in partial profile who holds a weapon, usually a blade, in one hand and a human victim or its head in the other. Sometimes, you can see the throat-slitting, as Ms. Bergh points out, shining a small flashlight on a ceramic figure already placed in a vitrine. "They did do human sacrifice," she says, though "there is no evidence that it was widespread."

Hide Pouch |

At one point, Ms. Bergh stops before a piece with pride. Her museum fought for this rare hide bag last year at auction—paying $146,500, more than twice the high estimate. On it is a modeled human face painted with geometric designs of the elite. The real human hair that surrounds the face still glistens. This object "has the same kind of facial features and tunic as other pieces nearby," she says, "but we don't really know who he is, or if he's a real figure at all."

In a way, he symbolizes the entire exhibition, which is full of mystery and ambiguity. It practically begs for more study -- which was part of its point, Ms. Bergh says. "We are trying to attract scholarship."