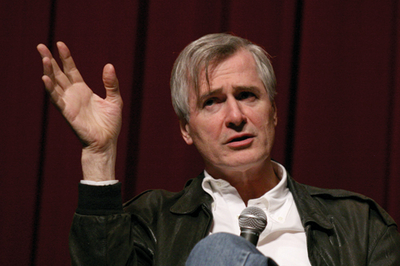

Spend some time with John Patrick Shanley, the author of "Doubt: A Parable," and you will see why he is one of today's most successful playwrights: He's a master of the entertaining line that lingers.

One sample: What did "Doubt," which won the Pulitzer Prize for drama and the Tony Award for best play in 2005, do for his career? "'Doubt,'" he replies with a sly grin, "balanced my obituary. Until 'Doubt,' I was the guy who wrote 'Moonstruck,'" the Oscar-winning 1987 movie about love, Italian-American style. "When 'Doubt' came along, I was like 'thank God. It will have something else to say.'"

That may be true, though Mr. Shanley is just 62 and probably has more productive years ahead. But "Doubt," a provocative drama about the battle between a parish priest and a strong-willed nun who suspects that he is abusing a student at her school, has given him much more than that. Soon after the play opened on Broadway, co-producer Scott Rudin asked him to turn it into a film, which starred Meryl Streep as Sister Aloysius and Philip Seymour Hoffman as Father Flynn, and invited him to direct. "It was a rare opportunity that you can't turn down," Mr. Shanley says. "I had directed, but not in 17 years. I knew I had to do it." His previous effort, "Joe Versus the Volcano," had bombed at the box office, cutting short his Hollywood directorial career.

And now Mr. Shanley has written "Doubt" for a third medium, opera. It will premiere on Jan. 26 at the Minnesota Opera in Minneapolis. His work as librettist has opened a new creative avenue for Mr. Shanley and possibly made a saint of the composer, Douglas J. Cuomo, who approached Mr. Shanley with the idea.

As Mr. Shanley unspools the tale, Mr. Cuomo invited him to lunch to discuss it. "I was going to tell him no, but I thought I should listen to him. Then, I forgot about the lunch, and felt so guilty about it that I agreed to do it," Mr. Shanley says.

As Mr. Shanley unspools the tale, Mr. Cuomo invited him to lunch to discuss it. "I was going to tell him no, but I thought I should listen to him. Then, I forgot about the lunch, and felt so guilty about it that I agreed to do it," Mr. Shanley says.

At the time, he'd seen only a couple of operas–"La Bohème" and "Simon Boccanegra"—and had listened to a few more. No matter. "I don't know how operas are supposed to be, but I do know when I'm bored," Mr. Shanley says.

He is also a self-described "theater guy." That means that he always wants to "change it now" when he sees something amiss. When "Doubt," the opera, went to its first workshop, "I started changing things within four minutes of walking in the door," he says. A doo-wop song, for example, was killed. But opera composers don't rush like that. "One time," Mr. Shanley says, "Doug locked himself in a room and wouldn't come out. He was trying to work." But, Mr. Shanley added, "The singers were waiting."

"In opera, you know the composer is the big gorilla, but he did not pull the big gorilla thing. He put up with me and I put up with him," says Mr. Shanley, who cultivates his tough-guy image and frequently directs his own plays. And, I ask over tea in his brightly hued Brooklyn apartment, did you insist on your way? "Oh, I insisted about 20 times a day," he says. "I'm not a big control guy. Things don't have to be my way; they just have to be good."

Mr. Shanley, the fifth and last child of an Irish immigrant father who esteemed manual labor, readily admits that he doesn't know a mezzo from a soprano. "I should not be trusted in this area," he says. (Sample: "Denyce, ah, what's her name, plays Mrs. Miller. I don't know what it is, but it's good." That would be Denyce Graves, star mezzo-soprano.) What he does know is the material. The play, he says, took "four or five weeks to write—or my whole life." Set in the 1960s in the Bronx, where he grew up attending parochial schools, it has four characters, including a young nun named Sister James and the boy's mother, Mrs. Miller, in addition to the priest and principal.

The Minnesota Opera wanted to preserve that small cast. "I said no," Mr. Shanley says. "That would be replicating the play. And to my amusement, they said 'OK.' Like that."

The way the story opens in each version says much about the medium. "The play opens with the priest giving his sermon to the congregation played by us, the audience," Mr. Shanley says. The movie, he says, "would be dead if we did that." He had to introduce the audience to Sister Aloysius, Father Flynn's accuser, right at the start to create tension. So, as Father Flynn preaches, Sister Aloysius moves among the schoolchildren admonishing some for various minor transgressions.

"In the opera," Mr. Shanley says, "I could go into the minds of the congregation, and have their voices in it." They call out for the priest's sermon. One working man, for example, sings that he comes to church because he cannot remain the same. He wants change, redemption.

After agreeing to write the libretto, Mr. Shanley went to see "The Marriage of Figaro" at the Metropolitan Opera. "I noticed they say the same things over and over," he said. "And you can explore it musically. If you have different language, you can't explore something musically. I went to Doug and said, 'these people need to be repeating themselves,' though I did that very little" in comparison with other librettists.

As a result, a scene with back-and-forth dialogue in the play might now have what Mr. Shanley describes as "overlapping dialogue," a braided conversation that becomes a musical duet. In Act II, for example, when Father Flynn consoles Sister James and earns her support, the braiding of their lines creates romantic frisson between the two. "The demands opera makes on language are different," Mr. Shanley says. "I have stuff that verges on lyrics. I changed the language to accommodate that." In the film, many lines come directly from the play.

Working with Mr. Cuomo, who has written a chamber opera based on the Bhagavad Gita as well as dozens of movie and television scores, Mr. Shanley would write "a chunk of the libretto" and send it to him. Mr. Cuomo would write the music, pass it back, and the pair would go through it together, note by note, with Mr. Cuomo plinking out the score on a piano. The musical result, Mr. Shanley says, "has a lyricism, it's not atonal austerity. There's romance in there."

Perhaps surprisingly, Mr. Shanley says writing the opera was easier than writing the film script. "I had people in black, talking endlessly," he says. "I had to use every trick in the book to make it cinematic."

"Doubt" has made him keen on opera. "I want to do it again," he says. "It has opened up a door." He even has a sure thing in mind: "I wish someone would commission me to do 'Moonstruck' as an opera. It was meant to be an opera."