BY the time John Singer Sargent reached his mid-40s at the beginning of the 20th century, he had long been saluted as the best society portrait painter of the Gilded Age. But he was having a midlife career crisis.

He was a darling of established critics, but to up-and-coming artists, he seemed old-fashioned. Around 1900, he put down his oils and turned to watercolors, capturing landscapes, gardens, exotic locales, and people at leisure, at work and at rest, often on his travels in Europe and the Middle East. Experimenting with unusual compositions and new techniques, he reinvented himself aesthetically.

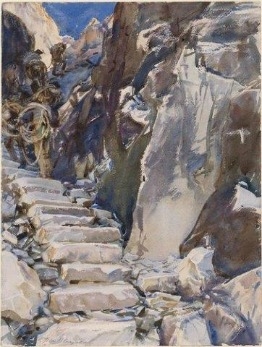

Carrara: Lizzatori I |

"These were years when he was very experimental," said Teresa A. Carbone, the curator of American art at the Brooklyn. Sargent was living in London, where watercolors were highly prized. His, though, were different from those of British watercolorists — more gestural, for one thing, and mystifying for their use of opaque watercolors at a time when they were typically translucent.

The lush results are not only "very beautiful," Ms. Carbone said, but also innovative in ways that are just now being appreciated — even by her and Erica E. Hirshler, senior curator of American paintings at the Boston museum, who collaborated on the exhibition.

Ms. Carbone planted the seed for the show in 2008, with an e-mail to Ms. Hirshler. "We were besieged by requests for loans of the Sargent watercolors, and I thought we ought to think about what we wanted to do with them ourselves," Ms. Carbone said. Her first thought was, why not unite the two collections? Ms. Hirshler agreed.

"Then it became more interesting," Ms. Hirshler said, as the two curators began their research. Among the things they discovered was that these works represented Sargent's own "vision of himself as a watercolorist at a very important moment." As such, they were far from tangential to his career.

Sargent, "an obsessive traveler" in the words of Ms. Carbone, would sit with his brushes and watercolors on his journeys, capturing the scenes before him, often from odd angles — low in a Venetian gondola, for example. He made dozens and dozens of images, many in a series, intending to keep them himself. When he allowed some to be exhibited in London in 1903, 1905 and 1908, they elicited mostly good reviews. But they were never for sale.

Then, in 1908, his friend, the Boston artist Edward Darley Boit — whose family was the subject of Sargent's renowned 1882 painting "The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit" — wrote to him. Boit proposed a joint exhibition at the Knoedler & Company gallery in New York. Sargent eventually agreed, probably to help his old friend's career.

As Ms. Hirshler recounts in her essay for the exhibition catalog, he wrote to Boit that "sketches from nature give me pleasure to do + pleasure to keep + more than the small amount of money that one could ask for them." He did not want to be bothered by repeated requests to see them.

Relenting slightly, Sargent raised a possibility: "... I really do not care to sell them — at any rate not piecemeal. If by any chance some Eastern Museum, or some Eastern collector wanted to buy the whole lot en bloc, I might consider it." His watercolors, he declared, "only amount to anything when taken as a lot together."

Sargent selected 86 watercolors and packed them off to New York, where they drew glowing reviews and crowds of viewers. Knoedler, aware of the artist's wishes, contacted museums in hopes of making a sale.

The Brooklyn Museum quickly made an offer for 83 of the watercolors (three were truly not for sale). Sargent hesitated, wondering if Boston, where he had more patrons and closer ties, was interested. Boit and his brother called the Museum of Fine Arts there, but its bid came too late and was smaller. Brooklyn won the trove for $20,000 (about $500,000 in today's dollars).

Soon Boit proposed another joint exhibition, and Sargent agreed. The date was set for 1912. This time, the Boston museum raised its hand early in the preparation for the exhibition, and before the opening it bought 45 watercolors for about $10,800.

As visitors to "John Singer Sargent Watercolors" will see, the two collections are very different.

Brooklyn's works are mostly smaller, freer, more expressive. Almost none are signed. Knowing that his next works would land in Boston, Sargent made them larger and more finished, and signed them.

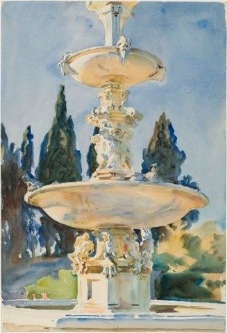

In A Medici Villa |

They are all spontaneous, she added, but it's also clear that Sargent "worked the sheets very aggressively. There are nuances, shifts in technique." Many, like "In a Medici Villa," from 1906, show Sargent as a master of reflected light. Some, like a series portraying the marble quarries above Carrara, border on the abstract. What he didn't paint is often as interesting as what he did.

One of Sargent's favorites, "Bedouins," from 1905-6, was shown and critically acclaimed twice in London before he sent it to New York. It shows two tribesmen, with faces sharply rendered; their garments are suggested as if the watercolors dissolved.

Some are reminiscent of his oils. "The Cashmere Shawl," from about 1911, is one. It depicts a woman in a white dress and patterned shawl, an example of his use of the wax resist technique, which left some spaces perfectly white. "It's a phenomenal work," Ms. Carbone said. "It's close to his regular portrait practice, but the whole sheet is executed all the way to the edges. It's freer."

In Brooklyn, the museum engaged a watercolorist to demonstrate six of Sargent's watercolor techniques, including wax resist and scraping, in videos that will be shown on small monitors in the galleries.

As they view these works, visitors will see, as many contemporaries did, that far from stagnating, Sargent was innovating in his watercolors. Yet it's easy to understand why appreciation of them faded. By 1910, abstract art was budding in Europe and America.

A year after Sargent's second exhibition at Knoedler, the momentous 1913 Armory Show in New York took place, changing everything in the art world. "His modernism becomes old-fashioned very quickly," said Ms. Hirshler. Sargent's reputation declined, and it wasn't until the 1950s that his oils came back into favor. Now, perhaps, is the time for his watercolors to regain their renown.