Silas Kopf, dressed in worn jeans and work shirt, hovers over a cluttered work table and traces the contours of a tiny eye – no more than a quarter of an inch across – onto six pieces of wood veneer of various hues. In seconds, he cuts them out with a string saw, beveling them so they fit together perfectly. Cemented with a touch of glue, they will form the nucleus of a colorful parrot he's creating from dozens and dozens of wooden pieces. Along with another parrot, both set amidst marquetry branches, it will eventually grace the front of a cabinet designed to hold over-sized illustrated books about birds.

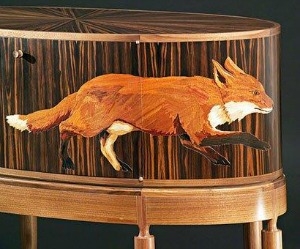

If you think marquetry is a dead art, a relic of the Renaissance, you haven't met Kopf. For more than 25 years, he has been turning out hand-cut marquetry marvels, some laced with humor, others as elegant as a classical commode, still others trompe l'oeil tableaus so realistic you do a double take. "I don't think anyone else in marquetry has his accuracy or range of colors," says Wendell Castle, the 80-year-old wood-master who is known as the father of the art furniture movement.

If you think marquetry is a dead art, a relic of the Renaissance, you haven't met Kopf. For more than 25 years, he has been turning out hand-cut marquetry marvels, some laced with humor, others as elegant as a classical commode, still others trompe l'oeil tableaus so realistic you do a double take. "I don't think anyone else in marquetry has his accuracy or range of colors," says Wendell Castle, the 80-year-old wood-master who is known as the father of the art furniture movement.

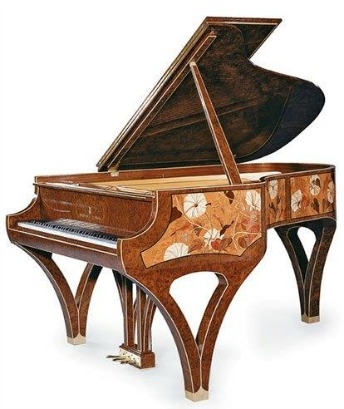

Kopf works his magic in a refurbished fire station in Easthampton, Mass. – a sprawling jumble of sawdust, wood samples, gum tape, masking tape, glue tubes, paper cups, pencils, sponges, drills, saws, sanders, and a World War II era veneer press. There he turns out tables, cabinets, desks, clocks, chairs, Steinway pianos and more. They're owned by museums including the Peabody Essex in Salem, Mass., the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Smithsonian Institution's Renwick Gallery and many well-heeled collectors.

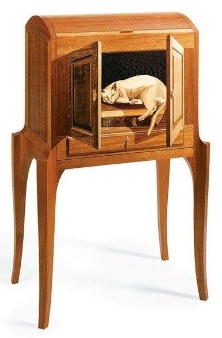

His pieces might be the centerpiece of a room, or serve as accents. Either way, they seem destined to be conversation pieces. One fall-front cabinet masquerades as an aquarium. A coffee table offers marquetry magazines. A lectern is fronted with faces, and a cabinet intended to house a collection of baseball memorabilia is decked out with, what else? A baseball and mitt. Says Kopf: "I want to make marquetry modern."

That wasn't his original goal. Kopf graduated from Princeton University with a degree in architecture. But this was the '70s. Kopf let his hair grow long and, instead of designing buildings, he decided to seek a future in woodworking. "My parents were mortified," he says genially (in unrelated developments, his parents came to approve and he has long since shorn his hair).

The woodworking world didn't exactly welcome him either. Attracted by the art nouveau furniture of Richard Newman, Kopf went to see him hoping for a job. Instead, Newman suggested that he seek an apprenticeship with Castle. So, Kopf says, "I called him and said I'd do anything." Castle, seeing no woodworking skills on his resume, turned him down. Undeterred, Kopf took a low-level job at a woodworking shop outside Rochester, N.Y. – not far from Castle's studio – and phoned Castle every three months to tell him what he was learning. "After about a year, Wendell called me with an opening," Kopf recalls. Nowadays, Castle calls Kopf "a natural," and the two remain in contact.

The woodworking world didn't exactly welcome him either. Attracted by the art nouveau furniture of Richard Newman, Kopf went to see him hoping for a job. Instead, Newman suggested that he seek an apprenticeship with Castle. So, Kopf says, "I called him and said I'd do anything." Castle, seeing no woodworking skills on his resume, turned him down. Undeterred, Kopf took a low-level job at a woodworking shop outside Rochester, N.Y. – not far from Castle's studio – and phoned Castle every three months to tell him what he was learning. "After about a year, Wendell called me with an opening," Kopf recalls. Nowadays, Castle calls Kopf "a natural," and the two remain in contact.

It was in Castle's studio that the marquetry light dawned. "I looked around at successful people, and they seemed to have a signature to their work," Kopf explains. Marquetry, which he says for decades had been "a retiree's hobby," looked like a good niche. Armed with a book, he started teaching himself how to do it. At first, he made simple jewelry boxes that he would sell at craft fairs. But within five years, "it was all furniture," he says.

His sights were raised again on a trip to Italy, where he viewed the work of Renaissance masters and fell in particular for a masterpiece of three-dimensional illusion and detail made by Fra Giovanni da Verona, c. 1500. It depicts a cupboard with four doors, each with ten panels, each open at a different angle; inside lie two stringed instruments, two flutes, and a scroll of sheet music. "Look at the way the broken lute strings spiral behind the sheet music," Kopf says, pointing to the piece in a book he has written called "A Marquetry Odyssey."

Kopf began to add more details to his works, making them more "painterly." To improve his skills, he used a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship to study marquetry techniques in Paris. There, he found the work to be exquisite, but he felt French design was too weighted by the past. "My task was to extract what was interesting and turn it into my aesthetic," he says.

About half of Kopf's work sells through galleries, notably Gallery Henoch in New York, where Kopf had a show last fall that included a lottery for a $12,000 cognac cabinet. Kopf got that idea from 18th century master David Roentgen, who used the ploy in 1768 for his work and that of his father (their work was recently shown in a special exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art). "They sold 24 pieces, and that created their careers," Kopf says.

Commissions make up the rest of Kopf's work. These pieces start with an email or a phone call, followed by a conversation about the design and size. Kopf will then send drawings of his idea along with samples drawn from his vast "wood library" – which includes exotics like Bocote, Narra and Bubinga as well as many satinwoods, rosewoods, mahoganies and more. Once a design is agreed, Kopf get to work turning those drawings into reality, generally using about a dozen woods in each piece.

Commissions make up the rest of Kopf's work. These pieces start with an email or a phone call, followed by a conversation about the design and size. Kopf will then send drawings of his idea along with samples drawn from his vast "wood library" – which includes exotics like Bocote, Narra and Bubinga as well as many satinwoods, rosewoods, mahoganies and more. Once a design is agreed, Kopf get to work turning those drawings into reality, generally using about a dozen woods in each piece.

On average, Kopf figures that he and his assistant, who makes the casework from plywood, complete about a dozen pieces of varying sizes each year. He never repeats a piece without some variations in the design. And he strives to be adventurous – up to a point. Years ago, he crafted a six-foot-tall corner cabinet with ten rows of rats running across the front. Blaming his "overconfidence" at the time, Kopf says "Life is A Rat Race" eventually sold, but at a deep discount. That hasn't happened again.