THE next time you visit an art museum, look around — not at the paintings, but at the people in the galleries. It's a fair bet that women will outnumber men; even government statistics say so. More women than men study art, too, at both undergraduate and graduate levels. Art appreciation is a female predilection and so, you would think, is collecting. To buy art, you have to shop. Need I say anything about which sex has a proclivity for browsing — an essential element of buying, um, visual art?

But the walls in art museums tell a different story. As Leonard A. Lauder's recent gift of more than $1 billion worth of Cubist paintings, drawings and sculptures to the Metropolitan Museum of Art reminds us, the donor names inscribed on labels or etched into museum facades are nearly exclusively male. Think J. P. Morgan, J. Paul Getty, Albert Barnes, Norton Simon, Paul Mellon, Henry Clay Frick, Robert Lehman... The list goes on and includes contemporary barons of industry and finance like Leon Black, Steven A. Cohen, Paul Allen and Eli Broad. Over the centuries, as in most other areas, it's mainly men who have glorified themselves by amassing large collections of valuable work.

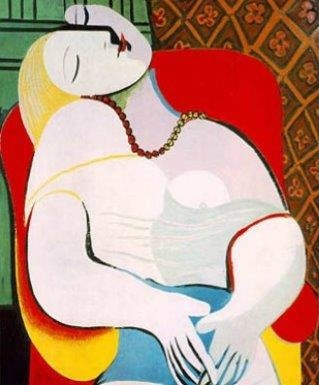

Le Reve |

The desire to possess, to collect, is inborn — neither male nor female — and as long as there has been art, there have been art collectors. The ancient Greeks did it, and so did the Romans. Cosimo de' Medici was a legendary collector, exceeded perhaps only by his grandson Lorenzo, who died in 1492. That year, Isabella d'Este was 18. Two years before, this daughter of the Duke of Modena had wed Francesco II Gonzaga, the Marchese of Mantua — and soon thereafter she cracked the collecting world's glass ceiling. A fashionista whose style sense spread beyond Italy to the French court, Isabella not only had a discerning eye for antiquities but also stirred interest in buying works by contemporary artists. Along with their art, she collected the friendship of Leonardo, Titian and Raphael.

In the 1700s came Madame de Pompadour, mistress of King Louis XV of France, who spent a fortune on art. She was followed by Catherine the Great, who — if anything — outdid her, often buying in bulk. In the United States, there were Isabella Stewart Gardner, one of the very few women with a major museum to her name here, and Louisine Havemeyer, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, Peggy Guggenheim, Gertrude Stein (an American in Paris), the Cone sisters and Doris Duke. More recently, Alice Walton, Agnes Gund and a few other women have made their marks.

But the operative word is "few." It is true that for a long time society thwarted female collecting. Confined to the home, women focused on furnishings, porcelain, jewelry, lace and the like, not great paintings and sculptures that made reputations. But that changed at least 100 years ago.

It's tempting to say that men still predominate because they control the money, and for the most part it does take a lot of money to become a great collector. But the explanation is too simple: many great collectors begin when the objects of their affection are out of fashion or underappreciated. Dorothy and Herbert Vogel, a librarian and postal clerk, respectively, who began buying art in the 1960s, amassed their renowned collection of contemporary art by living on her salary and spending his on art. Eventually, they gave some 5,000 artworks to museums.

There is a better explanation: collecting, at its highest levels, is more like hunting than shopping. Last fall, as I reported for a magazine article, Mr. Lauder described himself to me as "an incurable collector," then added, "The thrill for me is the hunt." That same general idea has echoed through conversations I've had with many male collectors over the years.

And who, by and large, are the hunters and the thrill-seekers of the world? Men. In traditional societies, men hunted to capture trophies and to win women as well as to provide food. They were in a competition; victory crowned them alpha males. It's not hard to see that men today see art collecting as a competitive sport. They may not be able to sink shots like Tiger Woods, but owning the best Picasso on the market produces the same visible pride.

In recent years, price records have regularly fallen for many artists because there's more competition at the top end of the market, not less, as in days past. Collectors seem to compete for the distinction of paying the highest price ever. Who bought that rare pastel, Edvard Munch's "Scream," for $119.9 million last year — why, Mr. Black. And who, this year, paid $155 million for Picasso's "Rêve"? Mr. Cohen, a man whose collection contains more than one record price. Women don't do that. The biggest female art acquisitor in recent years, Ms. Walton, tried to keep her purchases quiet. When she built a museum, she named it for a nearby spring, not herself.

Individuals are individuals, of course, and women don't lack the hunting instinct entirely. Lily Safra paid $104 million for a Giacometti in 2010, setting a record for the most expensive sculpture ever sold at auction. But men show it off more. And they have more money. (It doesn't hurt, by the way, that art is marketed these days as an investment. Some men, like David Geffen and Steve Wynn, have been masters at selling as well as buying, exhibiting their alpha prowess in yet another way.)

Gender parity in art collecting, as in so many areas, is a long way off.