The Bridle Path |

But, no. Marc Simpson, the art-history professor at Williams College (and former curator of American art at the Clark) who organized this exhibition, has chosen a different gambit. He sets up his thesis—that Homer mastered many media and explored many complex themes, most of which Clark collected—with a floor-to-ceiling wall of 63 wood engravings. Nearby are two lithographed sheet-music covers; one—"The Wheelbarrow Polka"—is dated 1856, the year Homer turned 20.

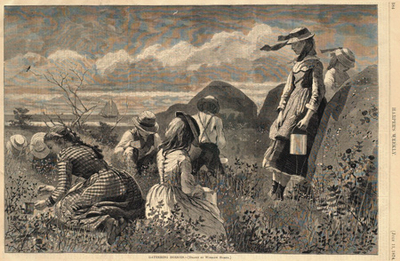

Gathering Berries |

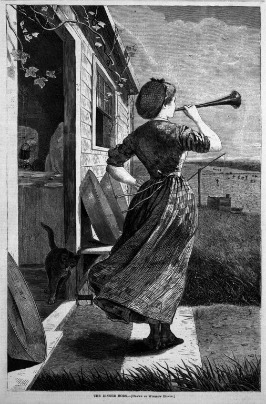

This unexpected arrangement in black and white—with no paint yet in sight—has a clear goal: It prompts viewers to stop and really look at Homer's images. Some are familiar. "The Nooning" (1873), a charmer that captures three boys lazily passing time in a field with an equally indolent dog, was preceded a year earlier by a similar painting of the same name with just one of the boys, now owned by the Wadsworth Atheneum. "Snap the Whip" (1873), an image of children united in play that Homer reprised in two paintings, is here. "The Dinner Horn" (1870), here engraved for Harper's, becomes a luminous painting that is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art.

But many are much less known. "Thanksgiving Day, 1860—The Two Great Classes of Society" (1860) shows Homer as social commentator. One side portrays "Those who have more Dinners than appetite"—a layabout; dolled-up theater-goers in their box; a woman being groomed by her maid—and the other, "Those who have more appetite than Dinners," depicts a boy handing a small loaf of bread to his mother; a gaunt needle-worker in her garret; a thief snatching a chicken.

The Dinner Horn |

Homer's drawings, which were turned into engravings, served many functions. Some were utilitarian, illustrating the news. Some served history, especially those documenting the Civil War. Others simply took readers to places or events they might not see in person—like horse-racing at Saratoga and yachting at Newport.

This panoply makes it obvious that Homer's illustrations frequently rose to fine art. He is not credited by some critics as always being a great draftsman, but he was when he wanted to be (or had time to be). Homer was also a resourceful artist. His people sometimes look similar, even alike, and he borrowed from himself all the time, turning people into types and reusing them in different situations, sizes, combinations, media.

But a print like "Gathering Berries" (1874), a classic Homer composition showing children at work in a field within view of a sailboat, against a hilly background and billowing clouds, has all the detail, depth, texture, light and other attributes of a great work. In Homer's paintings, those qualities sometimes seem obscured by his virtuoso brushstrokes.

Yet now visitors to the Clark are ready for those paintings, and 11 of them await in the next gallery, the high point of the exhibition. Five involve the sea, including "Undertow" (1886), that famous, forceful rescue scene that encapsulates Homer's recurring theme of nature's power over humans. For the technically minded, the Clark is showing six drawings in which Homer worked out the composition, but I suspect that many eyes will quickly be drawn to other walls of the gallery, where more pleasant paintings are hung. In each, Homer excels at combining image, atmosphere and meaning.

Sleigh Ride |

Homer (1836-1910) was a prolific artist. He painted more than 300 oils, and made hundreds of watercolors and drawings. In recent years, he has not been underexposed. Last year alone, the Portland Museum of Art presented an exhibition of his Maine paintings and opened his Prout's Neck studio to the public, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art offered a show centered on "The Life Line," his 1884 rescue scene.

Sterling Clark collected Homer for 40 years. His trove is missing a great Civil War oil, and has none of the beautiful pictures Homer made of women, to name two omissions. Yet not since the 1995-96 retrospective organized by the National Gallery of Art has Homer's career been explored so thoroughly. For that reason alone, "Winslow Homer: Making Art, Making History" is worth seeing. It continues through Sept. 8.