Hannibal, Mo.

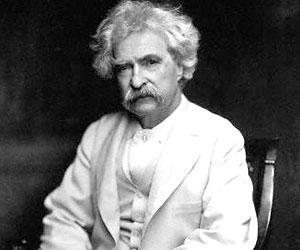

William Wordsworth wasn't thinking of anything remotely connected to cultural tourism when he wrote "the child is father to the man," of course, but for me those words have always served as a reminder to seek out the childhood homes of great writers and artists. So this fall, on a road trip through the American heartland, I headed for Hannibal, Mo., the little river town where Mark Twain grew up.

To get in the mood, I plugged CDs of "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" into my car's stereo system. Widely considered his masterpiece, "Huck Finn" has never been a favorite of mine. But Twain is so good that before long I was completely drawn in, eagerly anticipating the next chapter, and the next. When I arrived, I didn't want to get out of the car.

To get in the mood, I plugged CDs of "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" into my car's stereo system. Widely considered his masterpiece, "Huck Finn" has never been a favorite of mine. But Twain is so good that before long I was completely drawn in, eagerly anticipating the next chapter, and the next. When I arrived, I didn't want to get out of the car.

Hannibal seemed a sad, forlorn town. The short Main Street is home to undistinguished antiques stores, souvenir shops, a candy shop, a deserted hotel. Twain's name is everywhere -- not just on tourist attractions like the Mark Twain Cave, but also on the cheesecake restaurant, the beer distributor, the medical equipment company.

In the past few years, the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum -- eight properties in all, if you include the gift shop, which it does -- has been undergoing a revamping to emphasize "storytelling." In some parts of the museum trade, stressing narrative is perceived as negative, a kind of code word for using museum objects in a simplistic, sometimes ahistorical, way. But for a monument to master story-spinner Twain, it seemed somewhat appropriate. I proceeded to the small, white "Interpretive Center" at the top of Main Street without any sense of alarm.

Inside, simple wooden floors lined several galleries, adorned with posters and pictures describing, chronologically, how a poor boy named Samuel L. Clemens became Mark Twain. A few artifacts are interspersed here and there -- a period printing press, early editions of his books, and (I thought) a touching display of the model for a sculpture of Twain that fans had hoped to have cast in 1935 for the 100th anniversary of his birth. The requisite $1 million could not be raised.

Alas, the nice touches were frequently overridden by insipid wall texts. Consider: "Sam had plenty of fun growing up in Hannibal with his schoolmates, though sometimes their rough-and-tumble games ended badly. His family's financial problems didn't hinder Sam's kind of play." Huh?

Or, regarding the question "Was Tom Sawyer Mark Twain?": "Many of Tom Sawyer's escapades were based on Twain's own boyhood. Twain expressed his moods and character through many of the people in his novels."

Disappointed by the missed opportunity -- an Interpretive Center should set the scene and whet the appetite -- I moved on to the actual boyhood home at 206 Hill Street. Fittingly spare, it displays everyday artifacts of life on this particular bank of the Mississippi in the early 19th century: quilts, pots and pans, benches, beds, the infamous white fence. Though, it is true, there was little to engage, I wondered why the curators chose what seemed an odd note for a childhood home: In each room, the parlor, the dining room, the bedrooms, Twain appears as an apparition, a fully-grown all-white statue. Twain did, late in life, take to wearing an all-white suit year round. But this device, apparently meant to suggest a grown man reminiscing to visitors, struck me more as mannerism than anything else.

Exiting through the adjacent gift shop, which mercifully was filled mostly with Twain books and other Twainiana, I crossed the street to the home of Laura Hawkins, the inspiration for Becky Thatcher, which has yet to be touched by the revamping. There, it's easy to see why this complex of buildings needed an overhaul. For a start, the gift shop, chockablock with dolls and bonnets and other items totally unrelated to Twain, takes up the entire first floor, an area larger than the historical sections, which are upstairs.

Exiting through the adjacent gift shop, which mercifully was filled mostly with Twain books and other Twainiana, I crossed the street to the home of Laura Hawkins, the inspiration for Becky Thatcher, which has yet to be touched by the revamping. There, it's easy to see why this complex of buildings needed an overhaul. For a start, the gift shop, chockablock with dolls and bonnets and other items totally unrelated to Twain, takes up the entire first floor, an area larger than the historical sections, which are upstairs.

These rooms, an unprepossessing parlor and bedroom, lie behind plexiglass walls, remnants of 1950s-era historic-site museology. Visitors are asked to put a quarter into an old-fashioned device that plays a brief, recorded explanation of what's before them. Unfortunately, the audio I heard said nothing about Laura's role in Twain's life or books. It described her dressing for a party.

Next door, the Justice of the Peace's office, where Twain's father once worked, and Grant's Drug Store, to which the Clemens family moved during one period of financial troubles, are in an equally depressed state. Push a button, and you will hear a short audio explaining why you're there.

I quickly lit out for the final stop, a onetime department store now known as the Museum Gallery. It saved the day. The ground floor is split into five areas, each one portraying scenes from a Twain book. For "Huck Finn," visitors sit on a raft watching an excerpt from a movie based on the novel. For "The Adventures of Tom Sawyer," visitors move from one diorama scene to another -- watching Tom cajole friends into whitewashing the fence, visit the haunted house, sweet-talk Becky (push a button to hear the dialogue), and so on.

"Innocents Abroad," "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court," and "Roughing It" are also covered, though not quite as successfully. Still, the exhibits seemed aimed properly -- charming, but not condescending to, children, and yet engaging enough for adults.

Upstairs proved to be a treat. In 1935, Norman Rockwell was commissioned to illustrate special editions of "Tom Sawyer" and "Huck Finn," and 15 of his original paintings, plus several lithographs, are on view here. They are marvelous paintings. Here is Becky, clinging to Tom: "Tom, Tom, we're lost." Here is Tom, watching Huck, in straw hat with corncob pipe, hold a dead rabbit: "Lemme see him, Huck. My he's pretty stiff." And here is Huck, dressed up in a jacket, being eyed by Miss Watson: "Then Miss Watson took me in the closet and prayed, but nothing came of it."

Twain memorabilia fills the rest of the floor: movie stills from several productions; candids of Twain at his Elmira, N.Y., home; period newspapers; a gown he wore to receive his honorary degree from Oxford; his typewriter; letters he wrote and letters he received; Twain figurines, even Mark Twain flour bags.

But these flashes of enjoyment are far too infrequent to make the revamping a success -- so far at least. Twain was nothing if not complicated, colorful, wry and amusing.

The Boyhood Home and Museum is all earnest and flat and simple. It has no humor. Nor do visitors come away with a sense of Hannibal as a crucible for Twain's later life -- which was marked by mood swings, restlessness, financial speculation that ended badly, and pessimism about the U.S. For all his well-received humor, Twain was such a critic of American society, and American imperialism, that some labeled him a traitor.

Twain deserves better. No matter how much here is tagged with Twain's name -- this fall, aside from the permanent fixtures in Twain's name, the town advertised haunted Hannibal tours, a Twain birthday celebration with face-painting plus "photos with Mark Twain, Tom and Becky," the First Annual Wine and Blues Festival, etc. -- very little on offer would make visitors want to go home and read the books that made Twain famous.

And what would Twain himself have thought? I can't help citing a statement he made in 1907, three years before his death: "I like a good story well told," he said. "That is the reason I am sometimes forced to tell them myself."