The whole (art) world is watching. Since November 2013—when the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art announced it was scouring the country for artists who have been overlooked or underappreciated by major contemporary museums and galleries—curators, collectors and critics have been wondering what the institution built with Wal-Mart money would turn up. They'll find out on Sept. 13, when "State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now" takes over 19,000 square feet of the Bentonville, Ark., museum.

The exhibit, says Crystal Bridges' president Don Bacigalupi, is a "massively diverse" selection of 227 works by 102 artists. He and assistant curator Chad Alligood traveled more than 100,000 miles to find them, making studio visits to nearly 1,000 artists, most known only locally if at all. They were looking for art that fit three criteria: virtuosity, engagement and appeal—hardly top concerns of artists who bask in the light of the Whitney Biennial or a Chelsea gallery.

But, Mr. Bacigalupi insists, they didn't avoid controversy: "We wanted work that would engage people, not push them away, so even when artists here are asking tough questions, they are doing it in a way to open a conversation, not shut it down."

Those who made the cut range in age from 24 to 87. Fifty-four are male; 48, female. Geographically, they are spread evenly: 24 from the Northeast, 25 from the South, 26 from the West and 27 from the Midwest. A few are self-taught, but most have some education in the arts. Their pieces include paintings as small as 3.5 inches square and installations as large as a room.

Mr. Bacigalupi terms "State of the Art" a call to action—a challenge to art-world gatekeepers to look for talent around them instead of only in white-cube galleries and art fairs. "What we are attempting here is to rethink the shape of contemporary art in this country," he writes in the catalog. And as the show was being installed, he says, "Everyone will find something to engage with, something they've not seen before." Here, a few examples.

Justin Favela : Boys and Their Toys

Justin Favela : Boys and Their Toys

It's a car, it's a piñata, it's a monumental sculpture measuring nearly 20-feet-long and created by Justin Favela of Las Vegas. "Lowrider Piñata" is a souped-up, chromed-up, green-candy-colored 1964 Chevy Impala—made of tissue paper, cardboard and glue—that taps into Mr. Favela's Mexican-American heritage. It harks back to 1950s southern California, where Chicano culture cherished the pastime of cruising slowly and close to the ground in hydraulically modified, accessorized, custom-painted vehicles, in direct opposition to the sleeker, faster-paced cars of Anglo culture. The piece also nods to Mr. Favela's hometown, where visual culture is splashy, fast changing and not always what it appears to be, as well as to the centrality of the car in American culture, the expanse and thrill of the open road. But with "Lowrider Piñata," which hangs from a gallery ceiling, the artist also wants to entertain. "I love when people get a good laugh out of the work," Mr. Favela says in his statement.

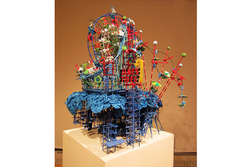

Nathalie Miebach : Art of the Storm

Nathalie Miebach : Art of the Storm

Everyone talks about the weather. Nathalie Miebach, based in Boston, puts it to work. Her woven sculptures, made of colorful reeds, rope, wood and beads, actually represent mammoth storms. Ms. Miebach records scientific observations of wind speeds and direction, humidity, moon phases, tide levels, temperatures and barometric pressure during a meteorological event, and uses the data to inform her sculptures—or, as she has tagged them, "3-D weather data visualizations." It's her way of understanding and communicating climate change.

Her three pieces in "State of the Art" relate to 2012's superstorm Sandy. If they look like toys, perhaps that's because they reflect what happened in amusement parks. In "I Dreamed She'll Ride Us All Again," for example, Ms. Miebach shows how three iconic rides—in Coney Island, Brooklyn and Seaside Heights, N.J.—endured the battering (two survived, one did not).

(Detail)

A. Mary Kay : Painting Isn't Dead

Nor, to look at A. Mary Kay's "Zenith," is beauty in art dead. Ms. Kay, born in England, works in a studio at the end of a dirt road in rural Lindsborg, Kansas (population: circa 3,500), and she is known locally for her poetic pieces.

"Zenith" is a lush, densely layered work rooted in the prairie of her surroundings. Stretching 18 by 7 feet, it's a meditation on the cycle of life—day to night, birth to death to rebirth—inspired partly by the dried plants, animal bones, seed pods and other products of nature Ms. Kay collects on walks. Intensely colored, "Zenith" combines the representational with the abstract in an exuberant painting that the artist hopes conveys "a place outside of language…that place where we know what we feel but we really can't exactly put a name on what that feeling is."

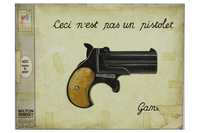

Tim Liddy : Subversive Games

Tim Liddy : Subversive Games

The creations of Tim Liddy, a St. Louis artist, require a close look. He makes enameled copper sculptures that seem to be found objects: the boxes of old board games, such as "Cootie" and "Battleship," that, he laments, children don't play anymore. But the painted trompe l'oeil packages convey what Mr. Liddy calls "biting and political" messages about racial, gender and social stereotypes. "Every game has a fiction in it," he says. Sometimes the whole game is imaginary. "Pistolet" references René Magritte's famous "Treachery of Images," a painting of a tobacco pipe with the text "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" inscribed below. But Mr. Liddy's "game" with its "Ages: Youth to Adult" label, also snarks at the country's gun culture. Another piece in the show, "circa 1953," is a Ouija board—supposedly supernatural, but also anti-religious—that is held together with tape that, somewhat sarcastically, forms crosses.

Matthew Moore : It's About the Land But Not Landscape

Matthew Moore : It's About the Land But Not Landscape

If he can't hold back the forces of change that will "within five years" transform his family farm outside Phoenix into suburbia, Matthew Moore, a fourth-generation farmer, plans to record the consequences. His "Lifecyles," a 26-minute, 30-second video, uses time-lapse images to illustrate how produce grows and to convey the hard labor involved. Mr. Moore has installed this and similar works, accompanied by evocative music, next to the real thing in supermarkets such as Albertson's. His point: teaching people that carrots don't just sprout fully formed in plastic bags, and that with every farming acre lost to suburbia or to ecological damage, the country is forfeiting something important to its history and culture.