New Britain, Conn.

Otis Kaye—you've probably never heard of him. Even many art historians do not recognize his name. But "Otis Kaye: Money, Mystery, and Mastery," a small exhibition here at the New Britain Museum of American Art, shows this eccentric artist, who sold only a few pictures in his lifetime (1885-1974), to be well worth knowing.

The exhibit heralds Kaye as a master of the still-life genre known as trompe l'oeil (which uses hyperrealistic images and shortened perspective to "fool the eye" into seeing the painted objects as real) and a less-successful practitioner of landscape and figurative art. Judging from the 34 works on view, though, there's a reason for that: Kaye seemed to be less interested in the latter kind of paintings. In contrast, he threw his heart into the meticulous, highly detailed, often autobiographical trompe l'oeil pictures, filling them with illusions and allusions. They are spiced with humor, too—sometimes silly, sometimes clever, usually sardonic.

Much about Kaye remains unknown. Even his birth name and that of his father, a German immigrant who settled in northern Michigan in the early 1880s, are uncertain. Around 1904, Kaye moved to Germany with his mother, studied engineering and draftsmanship, and then came back to the U.S., where he worked as an engineer, ending up in Illinois.

Much about Kaye remains unknown. Even his birth name and that of his father, a German immigrant who settled in northern Michigan in the early 1880s, are uncertain. Around 1904, Kaye moved to Germany with his mother, studied engineering and draftsmanship, and then came back to the U.S., where he worked as an engineer, ending up in Illinois.

Sometime in the 1920s he began to paint, focusing on the subject that would course through virtually all of his output: money. At first, he emulated the great American trompe l'oeil painters of the 19th century, such as William Harnett and John Frederick Peto, making comparatively simple compositions of paper money and coins.

But as his own fortunes changed, Kaye created more complex, layered works that convey his thoughts on the stock market, luck, morality, corruption and capitalism. The title of one work, from 1940, says it all: "Face It, Money Talks."

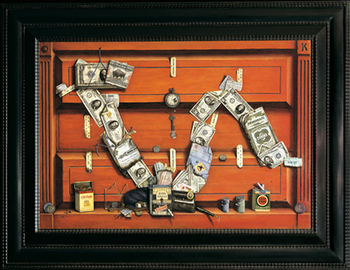

Money talks loudest, perhaps, in Kaye's "D'-JIA-VU?" (1937), the painting (pictured, top) that first interested James M. Bradburne, the departing director of the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, who curated this exhibition with Geraldine Banks, research coordinator for the Otis Kaye Family Trust. In 2010, the Palazzo Strozzi presented "Art and Illusion," a survey of trompe l'oeil from antiquity to the present that included "D'-JIA-VU?" It set Mr. Bradburne "on the trail" of Kaye.

In "D'-JIA-VU?"—a pun on déjà vu that refers to the Dow Jones Industrial Average—Kaye paints bonds and currency bills in the trajectory of the stock market, from the 1929 crash, when Kaye lost his family's $150,000 nest egg, to 1937, when the economy was heading into another recession. Below, along with a piece of shattered glass, are dice, cards and chips (labeled "Wall St. Poker Co.") that link investing with gambling. Tobacco packs carry the telling names "Old Gold," "Bond Street" and "Lucky Strike," suggesting that investments may well go up in smoke. A label on the "Bond Street" container reads "A Game of Probab" before reaching a tear, while the "Lucky Strike" pack says "It's toasted." The cards—an ace, king and jack—rest in a case that says "I O U U O ME." More than once, Kaye inserts his initials or his name into the composition, a poke at his own losses.

Technically, the painting is virtuosic: Every component, down to the shadows of the tobacco packs and matches, is realistic. Little wonder that "D'-JIA-VU?" is not only the centerpiece of this exhibition, but also Kaye's breakthrough painting. In 1996, "D'-JIA-VU?" sold at Sotheby's for $442,500, then and now the record for a work by Kaye.

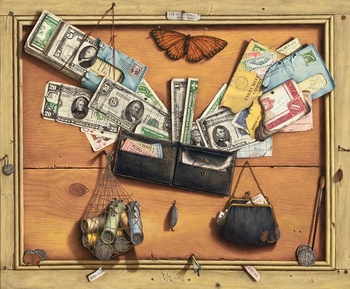

Many of Kaye's works are calligrams—that is, he arranged the elements to make literal images of his theme. "Face It, Money Talks" resembles a smiley face. "Easy Come, Easy Go" (1935) takes the shape of a butterfly, with bills fanning in and out of a wallet to form the large wings while a net full of coin rolls and a change purse hang below as the smaller wings (pictured, bottom). He pins a monarch butterfly above as a hint and, winking, he makes a smiley face from two nail marks and a groove in the wood background on the lower right, adjacent to his paintbrush.

"Nickel Dime Securities" (1950) is another example. In it, a $1 bill forms the base of a triangle whose other legs are made of $10 and $5 bills, on the left, and fire-tinged stock certificates, held together by ticker tape saying "U BOT TU HI," on the right. To the right, a blue business card for the president of "Nickel Dime Securities" hangs by a string: "A. Ponzi," a reference to Charles Ponzi, the pyramid-scheme swindler. Now, in case you missed it before, the structure of the work is unmistakable.

"Nickel Dime Securities" (1950) is another example. In it, a $1 bill forms the base of a triangle whose other legs are made of $10 and $5 bills, on the left, and fire-tinged stock certificates, held together by ticker tape saying "U BOT TU HI," on the right. To the right, a blue business card for the president of "Nickel Dime Securities" hangs by a string: "A. Ponzi," a reference to Charles Ponzi, the pyramid-scheme swindler. Now, in case you missed it before, the structure of the work is unmistakable.

Kaye sometimes reaches beyond the stock market for a theme—he takes up disappointment in love, the futility of war and the fickleness of fate, among other things—but he still weaves money into the picture. "Seasons Greetings II" (1969) comments on the commercialism of Christmas, for example. In it, Kaye fashions a Christmas tree from currency and stock certificates, stands it in a bottle filled with coins, and decorates it with gems and more coins. Then he trusses it with a ticker-tape garland bearing mottos like "GO FR OM RA GS TO RIC HES" and "UN OL, A FOOL AND HIS MON EE R PAR TED." The Bethlehem Steel certificate is made out to S. Klaus.

"My Cup Runneth Over" (1950s), another strong work, resembles a Dutch Golden Age still life, with three bowls offering succulent grapes, peaches, plums and apples. But money and stock certificates from, for instance, the "BANK OF RUPT COUNTY ILLIN[OIS]" peek out. One bowl is ringed with the words "BUY LO SELL HIGH" and "ENJOY FRUITS OF THY LABOR" and another bears a ticker tape saying "RAG S TU RIC HES OR IS IT RIC HE."

Though Kaye is an unrestrained jokester, he is a learned one—dropping in ancient coins and early American ones as well as common nickels and pennies. "Seasons Greetings II" refers to "C. Dickens" and includes a letter from Solomon to Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, the biblical characters saved from a fiery death by an angel. Nearly every painting is loaded—possibly overloaded—with similar examples.

For even the closest viewers of his works may miss some meanings. Kaye, a semirecluse in his later years, painted for himself. A critic of his times whose messages are still relevant, he made very original works that have received scant exposure and demand more decoding. This exhibit, Kaye's first in a museum, is a welcome step in that direction.