Around Maine

Think of Maine: lobster, blueberries, jagged coastlines, verdant forests, meandering waterways, beaches, boating, lighthouses. The sun rising over the foaming ocean and setting behind craggy mountains.

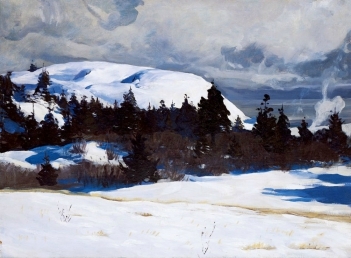

Kent's "Maine Coast" |

But if Maine's place in American art history is well known, its wealth in art museums is not. Nearly 20 years ago, the state set out to change that, creating the Maine Art Museum Trail. This year, it added the Monhegan Museum of Art and History, making a circuit of eight.

Last month, I traveled the trail, beginning with the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, located in an old fishing village about 35 miles south of Portland. Then I went north, mostly on I-95, to the Bates College Museum of Art in Lewiston, the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville and the University of Maine Museum of Art in Bangor.

From there, I turned south on scenic, winding two-lane roads lined with bright purple lupine, visiting the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick and the Portland Museum of Art in Portland. Between the Farnsworth and Bowdoin, I detoured to the new addition, taking an hour-long ferry ride (each way) from Port Clyde to the carless Monhegan Island.

By the end, I had driven about 425 miles and discovered a diverse array of art in these disparate museums, some 73,000 objects ranging from ancient Assyrian reliefs (at Bowdoin) to objects made in Maine in 2015 (at several).

This summer, a sampling can be seen in "Directors' Cut," a special exhibition at the Portland Museum composed of highlights chosen by the eight museums' directors from their collections.

Maine's favorite son, Homer, is (of course) present, humanized by Bowdoin, which sent historical photos, prints, drawings and letters, along with his well-used watercolor paint box. Early modernist Hartley, runner-up as the state's most esteemed artist, is represented by a painting from the Ogunquit Museum and in a display from the Bates museum, which was founded with a trove of paintings, drawings and archival documents bequeathed by Hartley's niece. Bates chose to show photographs and works on paper by artists in Hartley's circle, including Marguerite Thompson Zorach, John Marin and Mark Tobey. The University of Maine's museum focused on Abbott, who, though best known for her black-and-white photographs of New York City, lived in northern Maine for more than 20 years. In "Directors' Cut," you'll mostly see pictures shot during the Depression from her "Changing New York" series.

The Ogunquit Museum decided to showcase members of the artists' colony that sprouted there near the turn of the 20th century with a selection of traditional landscapes by the likes of Hamilton Easter Field. More interesting, to me at least, were its sculptures: "Young Girl" (1927) by Robert Laurent and "Ogunquit Torso" (modeled 1925, cast 1928) by Gaston Lachaise. These voluptuous versions of the female body, neither having anything to do with Maine, are among just a half-dozen three-dimensional artworks on display in "Directors' Cut," which inadvertently reveals how little sculpture has figured in Maine art.

Maine did produce one esteemed sculptor, by adoption: Louise Nevelson, born in what is now Ukraine, grew up in Rockland, though she moved to New York as a young adult. Still, the Farnsworth owns the second-largest public trove of her work and sent one of her trademark abstract, monochromatic assemblages, "Dawn Column I" (1959). Made partly from found wood and painted white, it was part of her early installation piece "Dawn's Wedding Feast," which was shown the year it was made at a landmark exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The Monhegan sent another of her sculptures, this one painted black, the small "Cryptic XXX" (1966). It is accompanied, smartly, by a little photograph illustrating her initial inspiration for these intricate pieces—the driftwood shacks on an island that she viewed from Monhegan.

Those two museums also allow comparison of landscape paintings by Rockwell Kent, too often known only for his illustrations. The Farnsworth's brushy "Maine Coast" (c. 1907), a relatively free rendition of a snow-covered meadow and mountain, contrasts with the precise "Monhegan, Village at Night" (c. 1950), a dark scene slashed by a glowing sunset, sent by the Monhegan.

Stuart's "Thomas Jefferson" |

Only the Portland museum defied expectations—with two contemporary sculptures and a dozen recent photographs by Maine artists, not a single landscape or seascape among them. Some images, like Paul D'Amato's view of a leggy transvestite, "Man in a Woman's Underwear, Portland Series: Underground" (1993), are even provocative.

But "Directors' Cut" is neither a substitute for the trail nor a narrative of artists who heeded the call of Maine. To get the full picture of what these eight museums offer, visitors must take to the road.

On my trip, the Ogunquit, wedged into a landscaped garden just off a winding residential road, was exhibiting a show of rural Maine photographs that has now closed. But aside from such changing exhibits, it has one gallery with selections from the permanent collection, including a row of representative landscapes by Hartley, Kent, Fairfield Porter and a notable Charles Burchfield, "North Wind in March" (1960-66). With red maple trees bent from the blast and snow falling from the clouds, "North Wind" can give viewers the chills.

Bates, also relatively small, has three exhibitions this summer, starting with an uneven sampling drawn from its permanent collection. I spent more time in "Points of View," recent photographs of Maine by four artists. Shoshannah White's black-and-white pictures of the root systems of native plants, captured by using technology that includes microscopic equipment, then modified slightly with paint, embellished with metal dust and encased in beeswax, are captivatingly ethereal.

Bates has also hung a gallery of photos of Hartley, dating from his youthful travels to formal in-studio images taken shortly before his 1943 death by George Platt Lynes. Among the most intriguing is a 1925 photo by an unknown photographer showing a frowning Hartley, in blazer, tie and khakis, sitting on the beach at Cannes and holding a document in his hand.

Next came Colby, whose 8,000-object collection spans art in America from colonial days to the present, spiced by small holdings of European, Asian, pre-Columbian and ancient art. The checklist of American artists there reads like a who's who (James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Thomas Eakins, Mary Cassatt, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Georgia O'Keeffe, Robert Rauschenberg, Sol LeWitt and Richard Serra, to name a few) and also contains lesser-knowns like California artists Joan Brown and Robert Bechtle. More important, nearly everything on view is of very high quality.

The galleries are hung beautifully—arranged chronologically and thematically with thoughtful juxtapositions. For example, Bechtle's lonely "20th Street—Early Sunday Morning" (1997), which uses light and shadow in an homage to Edward Hopper's "Early Sunday Morning" (1930), hangs not far from "Columbus Circle at Night" (2010), which plays with light and reflections of it in glass, by photorealist Richard Estes.

Colby's numerous strengths include two large galleries of Modernism (plus a separate wall of Hartleys), two walls of folk-art animals and two galleries of western art. I found many paintings and photographs to admire in the contemporary galleries, which—granted—are not filled with the transgressive works found at many museums. But several are enigmatic. Uta Barth's photograph "Ground" (1995), for example, is a light-filled, highly blurred, nearly barren landscape with only a few leaves in the upper right corner in focus.

Though on a campus with 1,850 students and in a town with a population of about 16,000, the Colby outshines many museums in much larger cities.

I moved on to the University of Maine museum, which concentrates on contemporary art. There, I found four exhibitions squeezed into a small space. One gallery contained selections from the permanent collection by Estes, Wyeth, Abbott, Katz and Marin. None stood out, so I entered "Blind Spot," a show of work by Anna Hepler, said to be one of Maine's best-known living artists. Ms. Hepler makes soft sculptures and large, patterned woodcuts. They relate to nature, but as with much contemporary art, they are also about process and materials. For example, she uses plastic bags to make crocheted pieces.

I soon departed for Wyeth territory—the Farnsworth, which celebrates Andrew, the most esteemed; his father, N.C., and his son James. Aside from its Wyeth Center, a separate building now filled with "The Wyeths, Maine and the Sea," the Farnsworth is presenting two large galleries of Maine watercolors by Andrew. As ever, his technical mastery is superb and his compositions, like "Southern Comfort" (1987), a light-filled portrait of his sleeping dog, are evocative. But the Farnsworth has much more, by many artists, including Fitz Henry Lane, Robert Indiana, Frank Weston Benson and George Bellows.

The Monhegan museum, charmingly unpretentious, is an outlier, jamming historical photographs and artifacts as well as paintings by artists who worked there into what once was the lighthouse keeper's home. The best works seem to have been sent to "Director's Cut," however, including "Gulls Descending" (c. 1960), a vivid close-up of four seagulls in flight by James Fitzgerald, whose estate was left to the museum.

The assistant keeper's house, filled each summer with a special exhibition, is this year showing Lamar Dodd, an academic from the state of Georgia who experimented with genres ranging from rugged realism to abstraction, but never found a niche that would bring him fame.

Bowdoin is the opposite of the Monhegan. Founded in 1813, it is one of the country's oldest art museums and aims to be encyclopedic. One of its masterpieces, Gilbert Stuart's portrait of Thomas Jefferson (c. 1805-07), was commissioned by one of the college's founders, James Bowdoin III, when he was designated as envoy to Spain. The painting has been interpreted as an assertion of democratic values: Though posed as a European royal would have been, Jefferson sits in a simple chair wearing simple dress; only in the background are a classical column and rich drapery.

Homer's "Wild Geese in Flight" |

Finally, I went to the Portland Museum, with its strong collection of American art, especially—yes—Homers, and a complement of contemporary art. No matter how many Homers you have seen by now, two here will stand out: "Weatherbeaten" (1894), showing a stormy ocean crashing against the rocky shore, and "Wild Geese in Flight" (1897), whose focus is not the birds in the title but two intertwined dead birds below them. Here, Homer deals magnificently with the beauty of nature, the confrontation between man and nature, and death itself.

Portland, too, is also the only place in Maine to see a broad collection of European art of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the only place to see how Courbet, Monet and others influenced American artists—not a bad way to end my time on the trail.

Having visited these eight museums in four days, I reflected on the circuit, which has many ups, a few downs and occasional misses. To no one's surprise, nature is a strong presence in the collections of these museums—even in the works of recent years, which perhaps is unusual. If I have one complaint, it is that the art is rather unadventurous. In a state as untamed as Maine, the art might have been, on occasion, a bit more bracing.