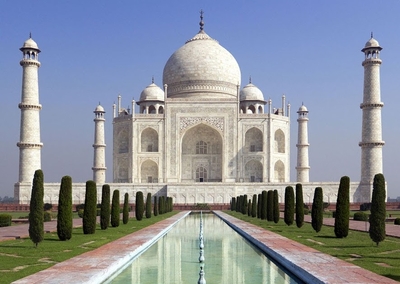

It's one of the world's most iconic sights: a straight-on, frontal view of the majestic Taj Mahal, filling the whole frame—almost confrontationally, except that there's nothing at all antagonistic about the Taj.

Truth is, that is not how visitors to the real thing in Agra, India, are introduced to this famous mausoleum. Nor is it the most enchanting view. Like a seductress, the Taj reveals itself in all its fullness only in stages, as a visitor wanders through the 42-acre site, drinking in the details, looking at it from all angles, and going inside, where photographs are forbidden. Some much vaunted monuments—the Great Wall of China or the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, perhaps—seem less impressive to me in person than expected. Not so the ethereal Taj.

Although the Taj can be seen from across the Yamuna River, it is hidden from arriving visitors. Past the ticket booths and security checks, a greensward leads to a two-level, square, red-sandstone gateway that hides that well-known view. Nearing this building—itself a beauty, decorated with floral inlays, calligraphy, corner towers topped by white cupolas, and 11 white-domed finials that sit atop its iwan, or vaulted entryway—one can see through its peaked archway to the Taj's gleaming white dome.

Although the Taj can be seen from across the Yamuna River, it is hidden from arriving visitors. Past the ticket booths and security checks, a greensward leads to a two-level, square, red-sandstone gateway that hides that well-known view. Nearing this building—itself a beauty, decorated with floral inlays, calligraphy, corner towers topped by white cupolas, and 11 white-domed finials that sit atop its iwan, or vaulted entryway—one can see through its peaked archway to the Taj's gleaming white dome.

That first glimpse, though it is likely to be partly obscured by other tourists, is nonetheless stunning. Poets have compared the Taj to a cloud, and in this view, with its moorings largely hidden from sight, it does look light enough to float.

Then, through the archway to the platform that faces it, across a garden with reflecting pools, the Taj appears just as the classic pictures show: Framed by four minarets—said to have been ordered as an afterthought by the builder, Shah Jahan, the fifth Mughal Emperor of India, precisely to set it off—the Taj sits on an elevated terrace, a model of symmetry. The reflecting pools capture its mirror image (providing more eye-pleasing symmetry), which is also framed, this time by a row of cypress trees trimmed into cylinders, aligned with and mimicking the minarets.

From this distance, the building's white marble exterior, showing mere hints of its carved and inlaid trimmings, looks lacy and feminine, and thus a fitting memorial to Mumtaz Mahal, the comely third wife of Shah Jahan.

Shah Jahan ruled from 1628 to 1658, a Golden Age of the Mughal dynasty. As the story goes, he was devoted to Mumtaz Mahal (variously translated as "jewel of the palace" or "chosen of the palace") and trusted her as a confidante. When she died in 1631 giving birth to their 14th child, he was devastated. In commemoration of their eternal love and his deep grief, he set out to build a wonder of the world, "a splendor for his sorrow," as the English poet Sir Edwin Arnold later wrote.

Shah Jahan spared nothing, drawing on his empire's deep financial resources and the artistic talent that had flocked to his court. According to a 1904 book by E.B. Havell, an influential English art historian, "The master-builders came from many different parts," including Baghdad, Delhi, Asiatic Turkey, Samarkand, Kannauj and Shiraz. Moreover, "every part of India and Central Asia contributed the materials; Jaipur, the marble; Fatehpur Sikri, the red sandstone; the Panjab, jasper; China, the jade and crystal; Tibet, turquoises; Ceylon, lapis lazuli and sapphires; Arabia, coral and cornelian; Panna in Bundelkund, diamonds; Persia, onyx and amethyst."

Shah Jahan spared nothing, drawing on his empire's deep financial resources and the artistic talent that had flocked to his court. According to a 1904 book by E.B. Havell, an influential English art historian, "The master-builders came from many different parts," including Baghdad, Delhi, Asiatic Turkey, Samarkand, Kannauj and Shiraz. Moreover, "every part of India and Central Asia contributed the materials; Jaipur, the marble; Fatehpur Sikri, the red sandstone; the Panjab, jasper; China, the jade and crystal; Tibet, turquoises; Ceylon, lapis lazuli and sapphires; Arabia, coral and cornelian; Panna in Bundelkund, diamonds; Persia, onyx and amethyst."

"Twenty thousand men were employed in the construction," he continues, "which took seventeen years to complete."

The paragon of Mughal architecture that they created blends Islamic, Persian and Indian styles, and uses curvy forms, symmetry, naturalistic floral decorative elements and a hierarchy of colors and materials to produce, well, harmony among four buildings and the central garden.

The Taj shares the arch-and-iwan structure of the gateway building, as does the mosque and the former guest house that flank the mausoleum at a respectful distance, and then outdoes them in so many ways. While the other three buildings are red sandstone, the Taj is covered in translucent, variegated white marble. While they are square, the Taj is built around an octagonal core. While they are flat-topped, the Taj is surmounted by that plump dome, reminiscent of a woman's breast—or a pearl. While they have cupolas at their edges, the Taj has a group that hugs the dome like ladies in waiting. While they seem bound to the earth, the Taj seems to touch the sky.

The exteriors of all four buildings are elaborately ornamented with carved arches, thin multifaceted columns that resemble stacks of miniature arches, floral inlays and calligraphic verses from the Koran. Inside, the Taj is far more beautiful. In the entry way, carved white marble true-to-life panels—bas-reliefs of tulips, poppies and other flowers sprouting from a mound—are framed with thin strips of black and gold, surrounded by a border of inlaid floral arabesques.

Then, passing through a door, visitors enter the darkened inner sanctum, lighted only by natural sources and a single Islamic hanging lamp. White marble screens, pierced with decorative patterns, keep visitors from getting too close to two sarcophagi, which sit side-by-side on platforms. There are two because Shah Jahan is also interred here, not in the black mirror-image of the Taj that he had imagined for himself, but was never built, on a site across the river.

Then, passing through a door, visitors enter the darkened inner sanctum, lighted only by natural sources and a single Islamic hanging lamp. White marble screens, pierced with decorative patterns, keep visitors from getting too close to two sarcophagi, which sit side-by-side on platforms. There are two because Shah Jahan is also interred here, not in the black mirror-image of the Taj that he had imagined for himself, but was never built, on a site across the river.

Her tomb lies at the center. His, which is bigger, perches on a higher mount slightly to the west (nearer Mecca) of hers. This is the only place where symmetry is noticeably violated, and it might be jarring were it not for the eye-catching floral gem inlays that blanket both white marble tombs, as well as their platforms. Hers also bears calligraphic inscriptions of the 99 names of Allah. (In keeping with Muslim tradition barring such elaborate decoration of graves, Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan are actually buried in a crypt below this chamber.)

The marble screens, interestingly, do not act as barriers: This is a place where people linger, gazing through them and circling through the arched bays surrounding the inner chamber, which bear designs matching the exterior.

Outside again, the Taj begs inspection from different angles. The best is looking up to the dome from near the base of the building: It resembles the moon rising above the horizon.

To appreciate the Taj's status as an architectural marvel, it is worth paying a visit to the so-called Baby Taj, built between 1622 and 1628 for the grandfather of Mumtaz Mahal and sometimes considered to be a first draft of the Taj. It, too, is made of highly decorated, inlaid white marble; it has arched doorways and four minarets surrounding a central rectangular chamber. But while beautiful, it seems squat and lacks grace, compared with the Taj.

Shah Jahan supposedly wanted his monument to his wife to represent her home in Paradise. We can't know if he succeeded on that score, but he clearly made a Taj that has attained immortality.