Steven M. Kossak began collecting the way many others do: first, rocks and butterflies, then coins and stamps, and eventually fine art, starting with old-master prints.

Then he took a different turn, going back to school at 36 to earn a graduate degree in art history, joining the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a research assistant, and ascending to full curator in the Asian Art department.

It was an excellent hire, one still paying dividends a full decade after his departure. On June 14, the Met will open "Divine Pleasures: Painting from India's Rajput Courts—the Kronos Collections," an exhibition of nearly 100 works Mr. Kossak (pictured below) bought for himself. Worth millions of dollars, they are a promised gift from Mr. Kossak and his family.

It was an excellent hire, one still paying dividends a full decade after his departure. On June 14, the Met will open "Divine Pleasures: Painting from India's Rajput Courts—the Kronos Collections," an exhibition of nearly 100 works Mr. Kossak (pictured below) bought for himself. Worth millions of dollars, they are a promised gift from Mr. Kossak and his family.

As a collector, Mr. Kossak said, he had grown infatuated by these playful paintings, which were made in the small kingdoms of northern India from the 16th to 19th centuries. Inspired by Hindu myths and poetry, the imaginative, detailed scenes of love and life among the gods are painted on paper in opaque watercolors and ink.

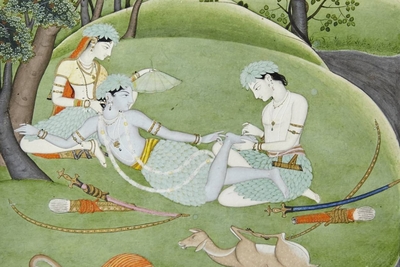

Their vibrant hues—reds, yellows, blues, golds, whites raised to simulate pearls and greens made with beetle-wing casings to sparkle like emeralds—are matched by their colorful titles. They include "Krishna and the Gopas [Cowherds] Huddle in the Rain," "Krishna Swallows the Forest Fire" and "Rama and Sita in the Forest: A Thorn is Removed From Rama's Foot" (above left).

Each one, he said, was bought because it evoked a visceral emotional response. "It's lightning-bolt recognition across the board," he said.

"They pack a wallop in content, style and beautiful color," said Vishakha Desai, an Indian-art specialist and former director of the and president emerita of the Asia Society. "You can enjoy them whether you know the content or not. Any museum would want this."

Mr. Kossak's paintings also fill a gap in the Met's vast collections. Like other museums, it privileged India's more subdued, Persian-influenced Mughal paintings over indigenous work from the north.

Mughal paintings were popular with wealthy collectors, foreign royalty and Russian czars, and museums followed suit, said Milo C. Beach, an Indian-art specialist and former director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery, the Smithsonian's museums of Asian art. In contrast, he added, Rajput paintings are more colorful and reflect what can still be seen in India today: "It's a much more alive kind of painting."

"Because of this gift," he continued, "the Met will be unrivaled in Rajput paintings among American museums."

Mr. Kossak began collecting Indian paintings in the late 1970s, and the core of his collection, purchased largely from dealers and sometimes in clusters, was formed before he joined the Met's staff.

While at the museum, from 1986 to 2006, he did what he could to form a substantial Rajput collection. But, he said, "When the Met couldn't afford it, I bought it."

There was no conflict because the Met knew and acquiesced.

"The basic rule at the Met then was one of trust," said Philippe de Montebello, the museum's director at the time. "He would have brought it to the attention of the museum, and said 'If you're not going to go after it, then I will.' "

"That's about as good an arrangement as you can possibly have," said Mr. Beach.

"That's about as good an arrangement as you can possibly have," said Mr. Beach.

Born to wealth, Mr. Kossak never had to earn a living. His spacious Midtown Manhattan apartment, with an East River view, is filled with art from his many collections: African, Oceanic, pre-Columbian, Asian sculptures and prints.

Before being moved uptown to the Met, some Rajput paintings hung on his walls; others, unframed and loose, were enjoyed hands-on, allowing the close inspection and intimate experience their former royal owners would have enjoyed.

Mr. Kossak, credited by many for having, in art-world parlance, "a great eye," started visiting museums and taking painting classes as a child and buying prints in high school. He studied studio art at Yale, then earned a master's degree in painting from the Maryland Institute College of Art, making work, he said, that was "figurative, realist."

He no longer paints, but he plays the cello, which he also studied. His instrument of choice was made by the great Venetian luthier purchased after he sold his Stradivarius. He prefers the darker timbre and friendlier feel of the Montagnana.

Mr. Kossak hasn't had the Rajput collection valued, he said; tax deductions can't be taken until the paintings are physically transferred to the Met. Early on, he would have paid less than $50,000 for one of these paintings, sometimes much less. Now, dealers say, many fetch $500,000 to $800,000, and the rarest masterpieces go for a few million dollars each.

Mr. Kossak estimates the value of his gift today at $15 million to $20 million.

To accompany the exhibition of his works, the Met is presenting a concurrent show of 22 of the many Indian paintings it acquired under his guidance: "Poetry and Devotion in Indian Painting: Two Decades of Collecting" is, appropriately, a celebration of his tenure there.